The Last Emperor, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, places special emphasis on the ways in which costumes determine an individual’s status in society. The color and cut of the costumes donned by each character helps the viewer to understand the personality of each character. However, the one sequence within the movie that deviates from this motif is the first sequence in which the prisoners of war recognize Phu-yi’s face and bow to him as if he is still on his throne. I argue that the costume Phu-yi wears during this sequence distinguishes him from the other POWs, and that ultimately his position as emperor transcends his current identity as a POW within Maoist China.

When the viewer first sees Phu-yi in The Last Emperor, he is disembarking a train on the Manchuria-Russia border as a prisoner-of-war. Phu-yi has been brought in for detainment and questioning because he is believed to be a counter-revolutionary.

(03:17). A still of Phu-yi as he exits the train (http://putlocker.is/watch-the-last-emperor-online-free-putlocker.html)

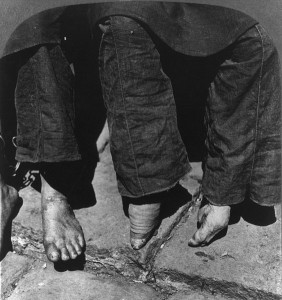

The setting where the sequence takes place is dark and industrial. The sky is cloudy, the ground is damp, and the POWs are being escorted by soldiers. All officers are wearing dark-green uniforms, and the other POWs are dressed in winter gear in dark green, dark grey, or black. Phu-yi stands our from the crowd because he is wearing business formal clothing in the form of a suit-and-tie. He wears a fedora instead of a fur-lined winter hat, and he is wearing glasses. From this still, the audience can infer that he was an intellectual, or at least worked in white-collar jobs prior to becoming a POW. When he enters the great-hall where the other POWs are waiting, they all turn to stare at him, with wary recognition. Some of the POWs bow towards him even though that is considered disobedience and could lead to death.

People bowing to greet the Emperor as guards take them away. Phu-yi is in the far-right of the frame, watching in disbelief. (http://putlocker.is/watch-the-last-emperor-online-free-putlocker.html)

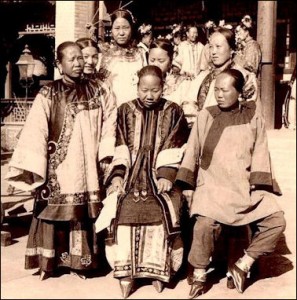

This is the only time in the film where Phu-yi’s costume did not accurately portray his identity or indicate to people how he should be treated. As a young child in the height of his reign, Phu-yi was best remembered as wearing the yellow imperial robes. In the photo below Pu yi has emerged from the Forbidden City to conduct a ceremony. Historically, the color yellow is reserved for royalty, and is only worn by the emperor.

Emperor emerging from the forbidden city (https://s3.amazonaws.com/criterion-production/stills/5743-62a71c78f340a4150192cf4a0d3899e2/Film_422w_LastEmperor_original.jpg)

Even when Pu yi is forced to evacuate the Forbidden City, he is still recognized as the Emperor in Japan due to his expensive attire. The Last Emperor proves that costumes are not necessarily indicative of how a character inhabits and navigates the setting around them. The Last Emperor tells Pu yi’s story through flashbacks as he is questioned by the communist army. What matters most for Pu yi is not his current status as a POW, which is implied by the suit he wears entering the prison and the mao suit he is forced to wear during questioning. His story shows that people will remember him as emperor because he served as emperor and wore the robes. His cultural relevance in Chinese collective memory will always command respect from people around him regardless of his official title and the clothing he wears.

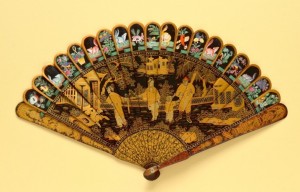

Brise fan made in France c. 1830 – 1840

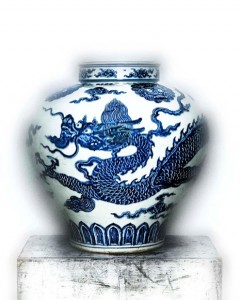

Brise fan made in France c. 1830 – 1840 Jar with Dragon. Early 15th Century.

Jar with Dragon. Early 15th Century.  Evening Dress, fall/winter, 2005-6. This piece was inspired by the Jar with Dragon.

Evening Dress, fall/winter, 2005-6. This piece was inspired by the Jar with Dragon. A Grey MaoSuit

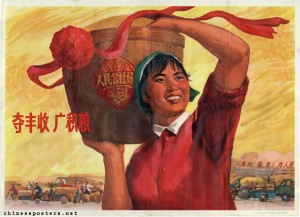

A Grey MaoSuit ‘Strive for an abundant harvest, amass grain 1973’

‘Strive for an abundant harvest, amass grain 1973’ Farmers during the Cultural Revolution, 1970

Farmers during the Cultural Revolution, 1970 (Katy Perry at the Grammy Awards in a Western interpretation of the qipao)

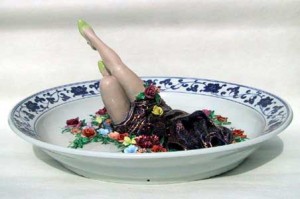

(Katy Perry at the Grammy Awards in a Western interpretation of the qipao) Liu Jianhua, Color Ceramic Series – Game, Ceramic Sculpture 2000, 52 x 52 x 23 cm, LJH30

Liu Jianhua, Color Ceramic Series – Game, Ceramic Sculpture 2000, 52 x 52 x 23 cm, LJH30 (Liu Jianhua, Color Ceramic Series – Game ,Ceramic Sculpture 2000, 61 x 61 x 15 cm, LJH12)

(Liu Jianhua, Color Ceramic Series – Game ,Ceramic Sculpture 2000, 61 x 61 x 15 cm, LJH12)