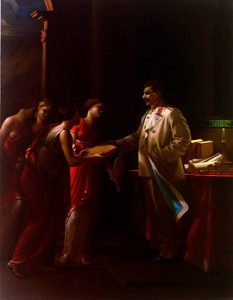

During the Stalin era in the USSR , systematic purges of thinkers and artists resulted in mass terror among these groups. By the late 1940s, the message for creatives from the regime was clear: comply, or risk your life. The official artistic doctrine was Soviet Realism, consisting of idealized depictions of the lives of typical Soviet workers. After Brezhnev’s death, the period of Glastnost began, which signaled an “opening” of the harsh constraints of the state. This was an interesting, exploratory period for Soviet artists, as they discovered exactly what they could get away with under the new order. Even after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, questions about how to artistically handle the legacy of the USSR arose. Instead of completely constructing a new “school” of art, post-Soviet creatives reached into the Soviet pass to construct their work. By ironically adding to and copying some of the Soviet Realist themes from the USSR, artists were able to make sharp commentary on the regime, both before and after its existence.

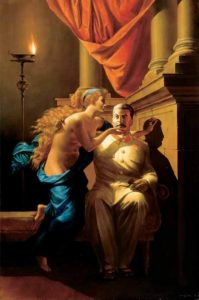

Irony is present in much late and post-Soviet art, especially art that recalls Socialist Realism and the realities of living in the Soviet State. In the SOTS-art (Russian pop art) school of painters, parody of Socialist Realism themes is a central tenant. Often, the prescribed themes behind a picture or work are exaggerated to an ironic degree, thus calling attention the the absurdity of the vast amount of sincere state propaganda preceding it. For example, in Komar and Melamid’s painting The Origin of Socialist Realism, complete irony interrupts a classic, Socialist Realist painting of Stalin. Stalin sits bolt upright in a chair, the picture of firm, guiding leadership. A muse has come to offer her services to him. He looks on without paying any attention to the muse. The title itself is ironic: The Origin of Socialist Realism may bring to mind a stolid, bad creation myth, but that could not resemble less of the truth. In reality, Stalin is gazing ahead, “creating” Socialist Realism, while the muse is attempting to whisper in his ear, to no avail. The inherently hilarious juxtaposition of the painting is evident. Socialist Realism could not possibly have been created by one of the least Socialist and Real figures around: a muse depicted artistically in a classical style.

The movie Window to Paris, created two years after the USSR’s collapse, also contains elements of irony that seek to push back against the tragedies of the past decades, and create a hopeful brand of art for the future. Although it an essential part of the movie, and an understandable one at that, the way in which Nikolai convinces the children to return to Russia is inherently unusual. Imploring them back into the state so many have been trapped in for so long is tragic, as they could feasibly complete their educations in France and return to Russia later. As one little boy says “Our parents will be happy when we stay”. And what parent wouldn’t want the brightest future for their children. The last irony of Window to Paris is exactly this. It is a borderline Socialist Realist value to place the future of one’s children behind the good of the state, yet this somehow prevails in this post-Soviet film.