“The Female Nude” highlights different representations of the Female nude across artists and its connection to selfhood and sexuality. Historically, The Female Nude has allowed artists to highlight culturally acceptable images of nakedness as it provides viewers to gaze upon the female body without “consequence” or guilt. This theme also addresses the standards of beauty relating to desirability.

The Female Nude has typically depicted the white woman’s body as desirable, an idealized representation of the standard of beauty. These objects focus on several depictions of the Female Nude, across mediums while projecting themes of sexual agency and individualism. They depict the ways BIWOC have reclaimed agency over the image of the female nude, challenging historic representations.

April 1977

2017

Collage

Mickalene Thomas is an African-American, contemporary visual artist whose art aims to re-envision female beauty, sexuality, and power. Thomas is known for her representations of Black women as confident, bold, provocative, and powerful. April 1977 depicts the female nude using a Black woman as the muse while pulling inspiration from Blaxploitation films. Blaxploitation films are a subgenre of exploitation films that debuted in the 1970s placing Black characters and the black community as main characters and heroes. These films perpetrated Black stereotypes but argued as a recuperative expression of Black empowerment. Thomas uses photographs of Black women from Jet Magazines pin-up calendars, Beauties of the Month, published between 1971 and 1977, in order to reclaim agency and challenge assumptions on beauty based on desire. The woman is posed on her knees, revealing her backside as she smiles and looks back, also making direct eye contact with viewers. The collage places the woman on a bed with silk sheets and her pose is sexy and confident; her gaze asserting power over her sexuality. Historically, the depictions of the female nude represent ideals of beauty and allude to desire, yet most of them are images of white women. Thomas puts Black women at the center as she challenges notions of beauty through desirability. In what ways does the reference to Blaxploitation films address selfhood and sexuality in this collage?

Sources: Winters, Edward. “Blaxploitation and Black Beauty: Mickalene Thomas – Beautés Du Mois.” Trebuchet-Magazine , 2020. https://www.trebuchet-magazine.com/blaxploitation-and-black-beauty-mickalene-thomas-beautes-du-mois/. Haughton, Aaron. “5 Of The Baddest Babes Of Blaxploitation,” February 3, 2018. https://www.viddy-well.com/top-5/babes-of-blaxploitation.

Compton Nocturne 2012

Color Lithograph 19 ¼ x 25 in National Museum of Women in the Arts, Promised gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore

Alison Saar is a multiracial, LA based sculpture, printer, and installation artist whose work relates to themes of the African diaspora, the way the body connects to identity, and the experience of powerful women complicated by race and gender. Compton Nocturne is part of her exhibition Mirror, Mirror, a collection of prints over the last 35 years, which explore self reflection as well as the relationship between identity and society. Many of the subjects in her work are informed by Greek, Roman, and African mythology. This piece is a re-interpretation of Saar’s sculpture, Compton Nocturne, which illustrates power in a woman reminiscent of an African deity. The image is based on Duke Ellington’s jazz song, “Harlem Nocturne,” known for its sultry qualities which connects to the bold depiction of the female nude in Saar’s print. Saar substituted Harlem with Compton, a predominantly African-American community in LA. The blue hues further the nocturnal aspect of the painting. Saar explains that the spirit bottle tree, originally a West African tradition used to lure evil spirits into upturned bottles, represents “her dreams that are being captured as opposed to wicked spirits that are trying to trespass.” The tree composed of her own dreams stemming from her head protects her despite her vulnerable nude position.

Sources: “Watch: Mirror Mirror: The Prints of Alison Saar Keynote Lecture.” Tandem Press, December 1, 2020, https://tandempress.wisc.edu/watch-mirror-mirror-the-prints-of-alison-saar-keynote-lecture/ Patterson, Tom. “Revealing reflections: Alison Saar’s prints and sculptures make bold statements at the Weatherspoon.” Winston-Salem Journal, January 25, 2020, https://journalnow.com/entertainment/arts/revealing-reflections-alison-saar-s-prints-and-sculptures-make-bold-statements-at-the-weatherspoon/article_6dc798ac-8fd0-5f8c-8e90-ff17bec9098b.html “Mirror, Mirror: The Prints of Alison Saar.” New Media Gallery, Toledo Museum of Art, July 26, 2020, https://www.toledomuseum.org/art/exhibitions/mirror-mirror-prints-alison-saar

Body En Thrall, p120 from Indigenous Woman,

2018

C-print mounted on Sintra,

48 x 32 inches (121.9 x 81.3 cm),

Edition of 8

Martine Guiterrez is a Brooklyn-based performance artist, who is often both the artist, subject, and muse of her works. Reflecting on her identity through the public and private sphere, Gutierrez explores societal constructs around gender, race, sexuality, and space. Body En Thrall p120 is one image from her Indigenous Woman art publication. Indigenous Woman featured images of Gutierrez and symbolism from pop culture to address identity as a social construct. In her Body En Thrall series, Gutierrez creates imaginative scenes around a pool while including slogans and imagery from the advertising industry. Body En Thrall addresses the power complex between one being held captive and holding someone captive. In this photograph, Gutierrez is posed with a mannequin with both her legs wrapped around his body. Gutierrez says “While gender is inherently a theme in my work, I don’t see it as a boundary. The only profound boundaries are those we impose upon ourselves. …Our interpretation of these constructs is subjective and not immutable. reality, like gender, is ambiguous because it exists fluidly.”

Sources: Martine Gutierrez: Indigenous Woman – RYAN LEE Gallery. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://ryanleegallery.com/exhibitions/martine-gutierrez-indigenous-woman/. M a r t i n e G u t i e r r e z. Accessed December 16, 2020. http://www.martinegutierrez.com/.

Origin

2018

Oil, Flashe, acrylic and fabric on canvas

84 × 72 inches

(213.4 × 182.9 cm)

Tschabalala Self is an African American figurative painter who seeks to explore the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality within the female nude. Origin combines sewn, painted, and collaged material as a way of reclaiming black identity in contemporary culture. This piece explores the beauty and complexity of the female nude through the unconventional and exaggerated representation of the female genitalia. The way in which the figure’s abstracted body emerges daringly from the canvas allows the woman to exist for herself, for her own pleasure, unphased by the viewer. Her role is not performative, her gaze is not vulnerable—the agency and pride she seems to have in her own naked body is unparalleled. Sexuality makes people uncomfortable,” Self says. “And if you’re dealing with women of color and their sexuality, it compounds all those anxieties.” These unflinching compositional choices boldly defy the misconceptions often surrounding the black female body while referencing Self’s relationship with her own body and culture. Though the figure is not Tschabalala herself, what does the depiction say about Self’s own sense of identity as a black woman in America?

Sources: Buck, Louisa. “Tschabalala Self: ‘what information is needed for one’s body to become gendered and racialized?’” The Art Newspaper, February 7, 2020. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/interview/tschabalala-self-asks-how-little-information-is-needed-for-one-s-body-to-become-gendered-and-racialised Christie’s. “10 Things to Know about Tschabalala Self.” Christies, February 11, 2020. https://www.christies.com/features/10-things-to-know-about-Tschabalala-Self-10259-1.aspx Gray, Arielle. “What Tschabalala Self’s ‘Out of Body’ at the ICA Taught Me About My Own Body.” WBUR ARTery, February 7, 2020. https://www.wbur.org/artery/2020/02/07/what-tschabalala-selfs-out-of-body-at-the-ica-taught-me-about-my-own-body ICA Boston. “Tschabalala Self: Out of Body.” Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://www.icaboston.org/exhibitions/tschabalala-self-out-body Kazanjian, Dodie. “Artist Tschabalala Self Upends Our Perception of the Female Form.” Vogue. April 13, 2020. https://www.vogue.com/article/tschabalala-self-studio-visit “Tschabalala Self”. Accessed October 28th, 2020. https://tschabalalaself.com

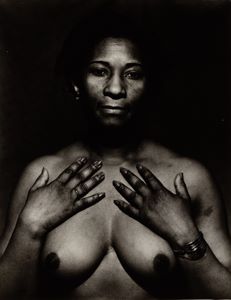

Black Nude Hands On Chest

1941

Printed in 1950’s

Early gelatin silver print on paper

14 x 11 in.

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Gift of Jon and Nicole Ungar

2016.46.219

William Witt, born in Newark, New Jersey, was a photographer whose images of New York City attempted to highlight its vibrancy. Growing up during the Great Depression, Witt was inspired by documentary photographers that showed the realities of life. His 1941 photograph Black Nude Hands on Chest places a nude Black woman against a pitch-black background, with her body being the brightest source of contrast in the image. The stark contrast of the image means that the highlights contour her figure while the shadowed elements soften in the background. This effect makes the viewer feel that her identity doesn’t matter, as her face – and by extension identity – is almost fading into the background, while focusing the viewer’s attention on the brightest part of her body: her bare chest. Witt being a white man raises questions about the historic objectification and sexualization of the Black female body by white men, and how it turns women into objects of pleasure. Does the model seem in control of her body, or is she portrayed as just a nameless nude body on display for our pleasure?

Sources: “Bill Witt.” Elizabeth Houston Gallery, July 15, 2019. https://www.elizabethhoustongallery.com/project/bill-witt/. Ganzel , Bill. “FSA Photographers.” FSA Photographers Document the Great Depression, 2003, livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe30s/water_14.html.