This theme examines the way in which artists have chosen to portray Black, Indigenous, Women of Color strategically through the subject’s pose and expression, commenting on how these artists have subverted traditional depictions of women in which male gaze often trumps the gaze of the female subject. In these objects, the women depicted actively demand attention, they command the space, and this is primarily illustrated in the way many of the subjects visibly and defiantly make eye contact with the viewer, as if challenging us. These women, in effect, are taking agency of their depictions, creating an exciting dialogue surrounding subject presence.

Engaging with this theme means directly engaging with the way in which the artists’ identities inform and reflect onto their depictions of these women. Who are these artists? What relationship do they have to their subject? How do the artists’ identities effect the narrative of their artworks and how do we see these narratives reflected?

Carrying water. Gee’s Bend, Alabama

1937

3 1/4 x 4 1/4 inches

Photograph

Negative : Nitrate Farm Security Administration

Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Arthur Rothstein was a Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographer born to Jewish immigrants in New York in 1915 who sought to highlight rural poverty during the Great Depression. On assignment to inspire support for the Bankhead Jones Farm Tenant Act, which allowed tenant farmers to purchase their own land, Rothstein headed to Gee’s Bend, Alabama to photograph the African-American sharecropping community there. Unlike many FSA photographers who portrayed their subjects as victims of poverty, Rothstein depicted them as survivors. The subject of the image, Annie Pettway Randolph, stands tall and looks at the viewer with bold eyes. Through balancing his compositions, Rothstein’s subjects claim more dignity by asserting their presence in the center of the image. Although Rothsetins uses pose to illustrate his subject’s dignity, his goal, like many other FSA photographers, was to inspire the viewers’ sympathy in hope of passing legislation. Because of the agenda Rothstein had while photographing the Gee’s Bend community, his images could be seen as propaganda rather than an effort to empower his subjects through his power as a photographer.

Sources: “Docent Endowment” North Carolina Museum of art, Department of Natural and Cultural Resource, March 2020, https://ncartmuseum.org/calendar/event/2020/03/29/artist_lecturealison_saar/1400/1530 Cooks, Bridget R. Exhibiting Blackness African Americans and American Art Museums, University of Massachusetts Press, 2011, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk9ts

Tell Me What You’re Thinking

2016

Chromogenic Print on Paper

39 ¾ x 49 ½ in

Bowdoin College Museum of Art Museum Purchase

Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund 2018.8

Tell Me What You’re Thinking was featured in Thomas’ first book, which highlights representations of Black women through photography. Tell Me What You’re Thinking depicts a Black woman lying comfortably in a highly decorative domestic setting while engaging in direct eye contact with viewers. Thomas mentions that in this series, she asked people from her immediate circle to pose for her. The controlled environment allows Thomas and her subjects to intimately react to each other. The variety of patterned fabric along with home objects creates an intricate scene that creates a conversation between the space and the model. The woman lies confidently, leg over the other, hand on her side as she looks ahead with pride. Is she welcoming, maybe enticing? Is she limiting access to what is beyond sight? In regards to this work, Thomas says “Any women — regardless of race, cultural identity or ethnicity — could look at these images and something about (the model) — her elegance, her glamor, her vulnerability, her confidence, her stance, her composition — will remind them of themselves.”

Sources: Mickalene Thomas. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.mickalenethomas.com/. Alleyne, Allyssia. “What Makes a Muse? Mickalene Thomas on the Power of the Model.” CNN. Cable News Network, May 31, 2016. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/mickalene-thomas-muse/index.html.

Tlazoteotl ‘Eater of Filth’, p 93 from Indigenous Woman

2018 ½ x 28 ½ x 1 ½ in

C-print mounted on Sintra, hand-painted artist frame

Bowdoin College Museum of Art Museum Purchase, Greenacres Acquisition Fund 2019.43

Martine Gutierrez, a LatinX woman of indigenous descent, is a visual and performance artist whose art seeks to explore how personal identity is formed, represented, and perceived by the artist and audience. Tlazolteotl, or ‘Eater of Filth’, is one of many Aztec archetypes that the artist portrays in her magazine, Indigenous Women. As the creative director, model, and photographer of the entire Indigenous Women collection, Gutierrez employs the well-known language of advertisements and pop culture to critique ideas about cultural and sexual individuality. A deity of vice and purification, Tlazoteol embodies the opposing concepts of duality and gender fluidity. In this piece, Gutierrez is adorned with heavy golden jewelry, an intricate braided crown, heavy makeup that drips in tears from her eyes – the result is beautiful, eccentric, and without a label. In this way, Gutierrez explores iterations of the self and attempts to break down the fabricated dichotomies and labels often perpetuated by society. “In my mind, labels are so divisional,” Gutierrez says. “We just need more people being, like, ‘This is my life.’”

Sources: Ancient Origins. “Tlazolteotl: An Ancient Patroness and Purifier for all things Filthy.” Ancient Origins, Jul. 20, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2020, from https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-americas/tlazolteotl-0010400 Calderon, Barbara. “Demons and Deities: Martine Gutierrez’sIndigenous Inspired Iconography.” Art 21 Magazine, Aug 1.2019. Retrieved November 27, 2020, from https://magazine.art21.org/2019/08/01/demons-deities-martine-gutierrez/#.X9krnS1h3s1 “Martine Gutierrez”. Retrieved Oct 21, 2020 from http://www.martinegutierrez.com

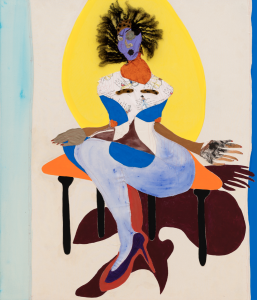

Princess

2017

7′ x 6′

Fabric, acrylic, flashe, oil and human hair on canvas

Tschabalala Self’s Princess is a part of the exhibition “Rock my Soul” which includes works from a variety of artists, aiming to meditate on how artists respond to conversations around self-representation, as well as abstraction and figuration in contemporary art. This piece traverses aesthetic borders, using a combination of mediums including human hair and fabric to create a vibrant, and colorful collage of an African-American woman with features including a blue face, cheetah-print collarbones and deep red stilettos. The figure exudes a powerful, demanding presence, haloed in yellow and dominating most of the canvas with her body and shadow. The Princess within the work, whose chest contains myriad collaged Disney princesses, is unnamed yet universal, magnificent and regal in her own right. Self implicitly begs the question of who “princesses” are and how the Black, female body defies and transcends ideas we may have about a “princess-like” presence.

Sources: Buck, Louisa. “Tschabalala Self: ‘what information is needed for one’s body to become gendered and racialized?’” TheArt Newspaper, February 7, 2020. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/interview/tschabalala-self-asks-how-little-information-is-needed-for-one-s-body-to-become-gendered-and-racialised Christie’s. “10 Things to Know about Tschabalala Self.” Christies, February 11, 2020. https://www.christies.com/features/10-things-to-know-about-Tschabalala-Self-10259-1.aspx “Tschabalala Self”. Retrieved Oct 15, 2020 from https://tschabalalaself.com