“Outside Looking In” explores the possible disconnect between the artist and the subject as well as the relationship between artist, subject, and viewer. The artist’s decisions of pose, gesture, and composition can either further the distance between artist and subject or bridge that disconnect. All the images included in this theme are photographs. This medium has its origins in documentational and anthropological photography which furthers the separation between artists and subject. Many artists go in to photograph their subjects with preconceived notions about how they want to portray them. Although photography is celebrated for being a medium that can capture reality objectively, the artist’s power to manipulate their subject must not be ignored when viewing these images. Another possibility for a disconnect between the artist and subject can be caused by the camera itself. Many non-contemporary photographer’s cameras were quite large, thus subjects had to wait for set up and were staged in certain positions. Although there are authentic qualities to photographs, staging subjects adds to the way photographers shoot through a subjective lens.

Gee’s Bend Alabama

1937, printed later mid-20th century

9 1/2 x 13 in. (24.13 x 33.02 cm)

Photograph North America,

American Gelatin silver print

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

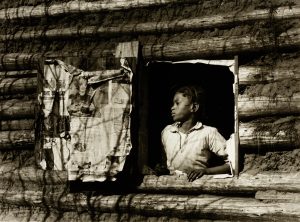

Arthur Rothstein photographed the sharecropping community in Gee’s Bend, Alabama in 1937 as a Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographer, after coming into the community as an outsider with the intent of photographing the epitome of poverty. The unidentified girl in this image titled Girl at Gee’s Bend, Alabama was later identified as Artelia Bendolph. The failure to identify his subjects is indicative of the distance created by sending northern white photographers, on an agenda to portray their subjects as single stories of poverty, to southern poor black communities. What Rothstein’s photographs leave out is that the Gee’s Bend community was not just a population of struggling sharecroppers but rather a group of thriving quilters. By not identifying his subjects and choosing only to depict their impoverished situations, Rothstein uses the unequal power dynamic between himself and the community to promote them to the outside world as victims of poverty rather than as artists. Although the image lends some dignity through pose and composition, how does Rothstein’s choice not to depict these women as thriving creators take away their agency as individuals?

Sources: “Photos, Prints Drawings,” The Library of Congress, accessed December 2020, https://www.loc.gov/photos/?fa=partof:catalog%7Ccontributor:united+states.+resettlement+administration Cooks, Bridget R. Exhibiting Blackness African Americans and American Art Museums, University of Massachusetts Press, 2011, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk9ts

William Witt

Black Nude and Radiator

1948

Vintage gelatin silver print on paper

14x 11 in.

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Gift of Jon and Nicole Ungar

2016.46.231

William Witt’s 1948 photograph Black Nude and Radiator depicts a nude Black woman wearing heels in a barren room. Here, the subject is turned away from the camera, almost as if she is unknowingly being photographed in an intimate moment. The bare, whitewashed background centers all attention on the naked model’s body, and her pose – crossed legs, hand on her hip, and face turned away from the camera – confers all agency and power to the viewer, who is voyeuristically observing her body as she is seemingly distracted. Not only does the viewer’s inability to see the model’s face take away her bodily autonomy and make it easier to objectify her body, but it creates a severe degree of separation between her and the viewer due to the lack of any clear relationship between the photographer and the model. The photographer captures a personal moment and makes it public, allowing the audience to stare at her body freely without fear that their gaze will be returned.

Sources: Digital, Dazed. “THE PHOTO LEAGUE: Remembering the Radical NY Collective That Brought a Social Conscience to Street Photos.” Artsy, August 6, 2013. https://www.artsy.net/article/dazeddigital-the-photo-league-remembering-the-radical-ny.

Pigment print (40 x 51 inches (101.6 x 129.5 cm)), 2007

Deana Lawson is a Black photographer from Rochester, New York, whose work primarily explores Blackness in its many forms. She employs tactics like staging her subjects powerfully within domestic settings and the subjects holding a strong gaze with the audience to convey their agency and almost otherworldly power. Her 2007 work Sharon, a 40×51 inch photograph on pigment print, is inspired by William Witt’s “Black Nude and Radiator”. In the original, the Black woman pictured doesn’t show her face, and it is as if the viewer happened to walk in on her. What is interesting about Lawson’s reimagining, however, is how much more agency her nude female subject possesses. Instead of simply being a naked body on display, Lawson’s subject confidently holds the gaze of the viewer, acknowledging our presence and almost permitting us to look at her in such a state of undress. She commands the otherwise simplistic domestic scene, illuminating just how much power a subject’s gaze can wield.

Sources: “Deana Lawson.” Rhona Hoffman Gallery. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.rhoffmangallery.com/artists/deana-lawson. “Deana Lawson.” Deana Lawson - 47 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.artsy.net/artist/deana-lawson.