Production & Gender

When we think of labor associated with the creation of textiles, we often think of such things as sewing, weaving, knitting, quilting, embroidery, and more. While not always the case, these acts are often seen socially as being feminine in nature. When we think about why this is the case, we might think about how a long history of patriarchy has subjugated women into the domestic and the familial realms, where before industrialization and vast consumer culture these skills were crucial to domestic and family life. However, it’s interesting to think about how, even in this day and age, we still hold on to and continue to teach (consciously or unconsciously) the notion that gender-linked textile production is a feminine pursuit.

Textile Production Across The World

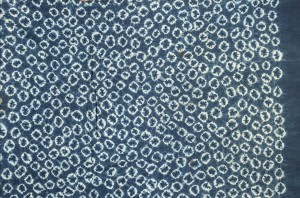

Unknown Nigerian Artist, Adire Wrapper, 20th Century

Unknown Nigerian

Adire Wrapper

Dimensions: 43 x 66 in. (109.22 x 167.64 cm)

Medium: textile/natural fiber

Date Created: 20th century

Nigerian Textile production is the largest employer in the country, but the labor market is not without strict gender roles. The artist of this particular textile is unknown, but the textile’s design reveals much of its history. This textile was produced by the Yoruba women in South-Western Nigeria. Only certain families in certain areas of Nigeria were allowed to produce Adire. The families would all wear this one textile, so they could easily identify outsiders. It takes approximately thirty-four hours to weave one yard of textile for the wraps. Then, the textile is dyed indigo, representing freedom and peace. The circular pattern on this textile was made by wrapping raffia around little stones. The role of women in the textile industry has changed dramatically in the last few centuries. Before the 20th century, women could gain power and fortunes through the farming, production, and exportation of textiles. During the 1900s, the rest of the world became infatuated with Nigerian textiles, and European and Nigerian men began dominating the textile market. Women’s work is now dismissed as unskillful as a way for men to reap the industry’s economic advantages.

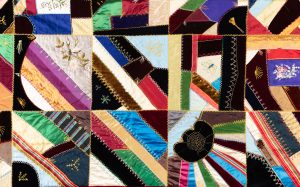

Esther Emily Lee, Fancy Quilt, 1890-1900

Esther Emily Lee

Fancy Quilt

Dimensions: 163.2 x 161.29 cm

Medium: fabric, silk, and velvet

Date Created: 1890-1900

While the quilt is labeled “Fancy Quilt,” these quilts are more commonly known as “Crazy Quilts” due to the abstract design and colors. Esther Emily Leslie produced this quilt circa 1890-1900 as a home decoration. Little is known about the artist, but her work is representative of crazy quilts of this era and women’s role in the production of textiles. The design and fabric choice of this quilt is prevalent during this time period. They tend to be made of silk and velvet fabric and have a darker color scheme influenced by the Victorian Era. Women would often use scraps of fabric to make these quilts, contributing to the design’s abstractness. The preservation of the quilt is representative of the purpose and importance of fancy quilts. They were often hung up on display and passed down through generations as a family heirloom. Women were the only ones to engage in this tradition. A good wife would not only care for the home and the children but also decorate the home with textiles.

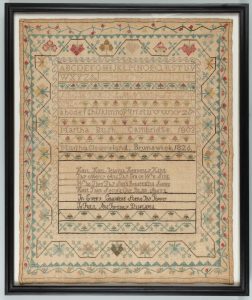

Marking Sampler

Martha Bush/Martha Cleaveland

Marking Sampler

Dimensions: 52.07 x 41.91 cm

Medium: silk thread on linen foundation

Date Created: 1803 – 1826

Samplers were a staple of a young woman’s education during the eighteen and nineteen-hundreds across the United States and in Europe. Created as a way for young women to practice and display their embroidery skills, girls made samplers while in school as a way of learning skills thought to be necessary for a woman’s expected role as a wife. For example, mending and embroidering decorative patterns. This particular sampler was created by Martha Bush who married Parker Cleveland, a professor at Bowdoin College in 1806. Interestingly, this sampler might show that these sorts of objects acted as generational teaching tools for young women. This is because this sampler has two different names, Martha Bush and Martha Cleveland, as well as two different dates: 1803 and 1826. The large difference in dates and the differing names might suggest that the sampler could have been started by Martha Bush and finished by her daughter, Martha Ann Cleveland. If so, this is showing the common practice of how a daughter learns traditionally feminine skills through her mother. Ultimately, samplers such as these are important because they give us an insights into the past. This particular example shows us how gendered forms of education supported the gendering of textile production as feminine in nature.