Nuclear explosions possess immense destructive power, capable of obliterating large cities with their blast and heat. However, it was the insidious peril of radiation exposure from nuclear fallout that emerged as the most formidable threat to human health during testing at Semipalatinsk.

Startlingly, just four tests conducted at Semipalatinsk stand are thought to be responsible for over 95% of the collective radiation dose inflicted upon the population residing in close proximity to the test site.1Gordeev, K., I. Vasilenko, A. Lebedev, A. Bouville, N. Luckyanov, S. Simon, Y. Stepanov, S. Shinkarev, and L. Anspaugh. “Fallout from Nuclear Tests: Dosimetry in Kazakhstan.” Radiation and Environmental Biophysics 41, no. 1 (March 2002): 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00411-001-0139-y. These tests occurred on specific dates: August 29th, 1949, September 24th, 1951, August 12th, 1953 (marking the first thermonuclear test), and August 24th, 1956. The cumulative impact of these tests resulted in a staggering burden of radiation on the local population.

During the era of the Soviet Union, the repercussions of nuclear tests on human health were shrouded in utmost secrecy. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1956 that the government finally conducted studies to understand the impact of these tests on the people residing close to the test site.2During the 1950s, a significant scientific expedition was conducted in the Semipalatinsk region. Leading the expedition were professors Atchabarov B. A. and Balmukhanov S. V. Their primary focus was to study the factors related to the influence of ionizing radiation on human beings. The expedition aimed to gain crucial insights into the potential health impacts of radiation exposure on the local population in the aftermath of the nuclear tests. As a result, there is a noticeable lack of clear statistics regarding the immediate effects of these nuclear experiments on the local population.

Initially, the Soviet authorities seemed relatively unconcerned about the potential harm caused by nuclear tests to nearby residents. Evacuations were rare, and only one instance occurred before the most powerful nuclear test in August 1953 [See previous post on the Soviets’ “Joe-4” bomb here]. However, even during this evacuation, the affected individuals were still exposed to the hazardous fallout emanating from the test site.

Of the approximately 116 atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at the Semipalatinsk test site had a significant impact on the environment. The public, particularly those living close to the test site, faced the highest levels of radiation exposure.3Grosche, B. “Semipalatinsk Test Site: Introduction.” Radiation and Environmental Biophysics 41, no. 1 (March 2002): 53–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00411-002-0141-z.

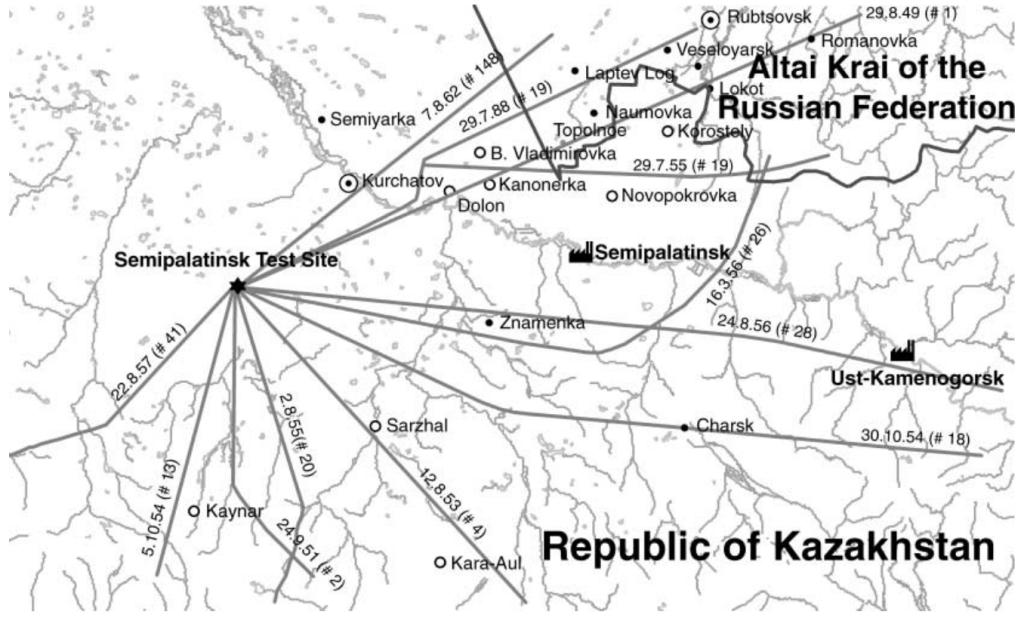

However, the consequences of these tests extended beyond the immediate vicinity. Inhabitants of areas further away, like the Altai region situated about 300 km northeast of the test site, were also considerably exposed to radioactive fallout. The first test in 1949 predominantly affected the Altai region, while the test of August 1956 had a major impact on the area around Ust-Kamenogorsk in the east, approximately 300 km away.

To assess the individual radiation doses received by the inhabitants, both external and internal exposures need to be taken into account. External exposure results from contact with the radioactive cloud and contaminated ground surfaces. Meanwhile, internal exposure occurs through the consumption of contaminated food, entering the human body through the food chain.4Grosche, Bernd, Tamara Zhunussova, Kazbek Apsalikov, and Ausrele Kesminiene. “Studies of Health Effects from Nuclear Testing near the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site, Kazakhstan.” Central Asian Journal of Global Health 4, no. 1 (May 8, 2015). https://doi.org/10.5195/cajgh.2015.127.

The fallout can be visualized using the schematic below.

Amidst the haunting remnants of a bygone era, a chilling truth emerges. Decades of nuclear testing have left a lasting impact across the Steppe. Unearthed survey data from as far back as 1949 unveils a disturbing trend: increased cancer incidence rates in villages exposed to the harrowing aftermath of nuclear detonations, a stark contrast to their unaffected counterparts in the Kokpektinskii district (the control area).5Ibid., pp. 2-3.

Seeking to comprehend the impact on children, Zaridze, Li, Men, and Duffy (1994) embarked on a comprehensive study of childhood cancer incidence in administrative regions bordering the test site–Semipalatinsk, Pavlodar, and Karaganda.6Zardze, Daid G., N. Li, Tamara Men, and Spephen W. Duffy. “Childhood Cancer Incidence in Relation to Distance from the Former Nuclear Testing Site in Semiplatnsk, Kazakhstan.” International Journal of Cancer 59, no. 4 (November 15, 1994): 471–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910590407. Delving into documentation of cancer cases in children aged up to 14 years between 1981 and 1990, they referenced census data from 1979 and 1989. Their meticulous analysis reveals a significant inverse association between incidence and distance to the epicenter of nuclear tests (air and underground test sites, atomic lake). Thus, acute leukemia and all cancers combined demonstrate higher rates in proximity to the test sites in the Semipalatinsk and (former) East Kazakhstan regions.

Further, a different study found that individuals living near the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site in Kazakhstan showed a significant increase in hypertension prevalence, which was associated with environmental radiation exposure, even after considering other cardiovascular risk factors.7Markabayeva, Akbayan, Susanne Bauer, Lyudmila Pivina, Geir Bjørklund, Salvatore Chirumbolo, Aiman Kerimkulova, Yulia Semenova, and Tatyana Belikhina. “Increased Prevalence of Essential Hypertension in Areas Previously Exposed to Fallout Due to Nuclear Weapons Testing at the Semipalatinsk Test Site, Kazakhstan.” Environmental Research 167 (November 1, 2018): 129–35. Link.

Despite extensive health research and earnest endeavors to establish conclusive connections between radiation exposure and disease data, obtaining epidemiological evidence for radiation effects continues to present a formidable challenge for researchers in Kazakhstan. The aftermath of the Soviet era, characterized by limited infrastructure and resources during the immediate post-Soviet years, along with the scarcity of consistent information and elusive primary documents for dosimetry, casts uncertainties on the journey towards absolute certainty.

Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that a consensus seems to emerge among scientists, suggesting that a substantial portion of the currently observed health effects can be attributed to exposure during the period of nuclear testing, rather than being a consequence of residual radioactivity exposure.8Gusev, B. I., Z. N. Abylkassimova, and K. N. Apsalikov. “The Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site: A First Assessment of the Radiological Situation and the Test-Related Radiation Doses in the Surrounding Territories.” Radiation and Environmental Biophysics 36, no. 3 (September 1997): 201–4. Link.

A review of many recent literature on the health effect from nuclear testing near the SNTS can be found here.