By Will Childs and Grayson Moniz

Throughout the 20th century, the economic proceedings of the Soviet Union were entirely under the jurisdiction of the government. They controlled the nation’s employment, production, and distribution. Most of the nation’s output was dedicated to industrial production and manufacturing at extremely high rates, rather than consumer goods. As a socialist nation, job security was virtually guaranteed, and unemployment was not a quantifiable issue. However, mass employment hindered the productivity and efficiency of the labor force and plagued the economy throughout the nation’s final years. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, it resulted in an unprecedented economic crisis, reflected in massive contractions of GDP and skyrocketing unemployment [1].

Grigorii Khanin’s “Economic Growth in the 1980s,” featured in The Disintegration of the Soviet Economic System (1992) provides valuable context for the conditions that predated the massive recession of the 1990s. He discovered that the nation had many underlying inefficiencies and stagnations that the economy endured prior to 1991, such as the over-centralization of production combined with slow technological innovation (compared to the United States). These factors directly contributed to the eventual dissolution of the union. Khanin’s analysis essentially highlights how certain deep-rooted issues made the USSR’s economy particularly vulnerable to both internal and external pressures.

The nation’s transition from socialism, with artificially high, government-mandated employment, to a market economy in 1991 generated astronomical disruptions to the workforce. The privatization of large corporations directly affected the employment of thousands of Russian citizens and caused a severe economic depression. The figures of this decline will be expressed in our data analysis, but it is one of the most unprecedented economic fluctuations in history.

At the onset of Russia’s transition to a market-based economy, President Boris Yeltsin introduced reforms to ease the transition from socialism to a market economy. His policies included removing price controls (which would result in an increase in prices) and privatizing government-owned businesses [3]. These efforts ultimately failed, generating inflation, lower production rates, and worse living standards, as well as causing a spike in unemployment [1]. The sudden shift was too much for the nation to handle, proving the importance of considering gradual implementation, especially when it comes to a scenario of economic—and social—reconstruction.

Analyzing Russia’s economy after the collapse of the Soviet Union offers valuable insights into the difficulty of economic reform and growth, conveying the consequences of poor government execution. The fast and chaotic nature of these changes is well illustrated by Vladimir Lenin’s famous quote: “There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks when decades happen.” As journalist Serge Schmemman wrote in a New York Times article, Russia in the early 1990s was “stripped of ideology, dismembered, bankrupt, and hungry,” yet the Soviet Union remained ‘awe-inspiring even in its fall.’ This captures the scale of the collapse and its lasting impact on history.

Data Analysis

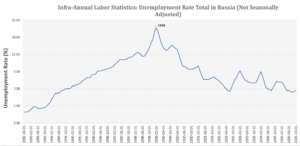

Even though there wasn’t any official unemployment rate (%) data available for Russia before 1992 in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, we infer that the unemployment rate had been increasing since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. The reason for our assumption is due to the fact that we know the unemployment rate was reported as being extremely low or even nonexistent during the Soviet period [2], which was supposedly due to the existence of government-mandated employment. This means that the unemployment rate was most likely sitting at a very low percentage (certainly below 4.78%, the rate in October of 1992) for quite some time before the collapse of the Soviet Union. From 1992 to 1994, we calculate that unemployment in Russia increased by the exorbitant amount of 56.85% [5]. The reason for this increase is due to the rapid transition from a state-controlled economy to a market-oriented one. After the collapse of the USSR, all of the mechanisms and policies that had been put in place to ensure full (or at least close to full) employment were dismantled, and many previously government-owned institutions were either privatized or shut down. This massive surge in unemployment in Russia was primarily driven by the collapse of the state-controlled economy, but the hardship experienced by workers was exacerbated by the lack of adequate social safety nets—including social security, unemployment insurance, and food assistance programs—as well as the absence of job retraining and workforce development initiatives that could have helped them adapt to the emerging private sector. The takeaway from this is that absence of these forms of support worsened the ability of newly unemployed workers to find opportunities during a period of transition and uncertainty, triggering a domino effect that pushed the unemployment rate from around 7% in 1994 to approximately 10% by 1996, where it remained elevated for nearly a decade (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

On the production side of the economy, the collapse of the Soviet Union caused a huge decrease in GDP per capita, which fell from 7,432 (2010) U.S. dollars in 1991, to 5,071 in 1994, which translates to a 31.8% decrease [7]. We analyzed GDP per capita instead of real GDP, because, during this time, Russia’s population had also been declining [8]. This sharp decline in Russia’s GDP per capita resulted from a combination of factors, including widespread supply chain disruptions, the disorganization of the labor market, and the challenges posed by the sudden introduction of newly privatized companies into the economy. In essence, the fact that the government controlled everything—factories, law enforcement, businesses, jobs—made it so that, when the socialist system crashed essentially overnight, several of these facets of the economy lost government funding (as happens in a market-based economy). By losing funding, some businesses shut down and others dramatically reduced their levels of production. At the same time, the lack of governmental control made prices of goods and services increase in an unstable manner, which made it hard for both people and businesses to afford necessities [4]. This increase in prices reduced GDP because all of a sudden not only is investment going down because firms are no longer running at the same efficiency and with the same financial flexibility, but consumers also aren’t spending nearly as much (consumption plummets). Additionally, we believe the decrease in GDP per capita shown in Figure 2 was also associated with a reduction in foreign investment. Even though it didn’t represent a large amount of Russia’s spending before the collapse—it was vodka and oil exports mostly [4]—the fact that trade was basically impossible with the amount of firms that were being put out of business amidst the instability made a difference in the rapid descent of GDP per capita. All in all, Figure 2 shows us that, even though GDP per capita wasn’t exactly increasing before 1991, the lack of political stability, solid economic policies and economic control in general cut Russia’s domestic production almost in half.

Figure 2

Source: World Bank.

Another intriguing aspect regarding the data is the sudden trend change on both Figure 1 and Figure 2 in 1999. Even though it’s not directly associated with the original research question, we were able to analyze how Russia started to recover from the collapse of the USSR. The stark economic recovery in 1999 is likely due to the sudden increase in world oil prices [9], which then allowed Russia to run a large trade surplus in the next couple of years. This explains the rise in GDP per capita after 1999 as well as the decrease in the unemployment rate at that same time. This is yet another example of how a shock (in this case, a positive shock for Russia) can have such a meaningful impact on a country’s economic well-being (the rise in oil prices was arguably an indispensable factor in Russia’s economic comeback).

Conclusion

We found that the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 catalyzed a nationwide disruption to the economy that directly affected the employment and GDP of Russia decades later. This project serves as a case study for the calamitous repercussions of rapid economic transition and the vitality of mitigating harmful shocks to the economy. It would be interesting to examine regional variation in economic indicators when Russia transitioned to a market-based economy, presuming some areas were more resilient to the change than others. Nonetheless, exploring and analyzing the data for this research question offered valuable insight into how major macroeconomic shocks can have seismic effects on the course of a country’s economic history.

References

- Ellman, Michael, and Vladimir Kontorovich. The Disintegration of the Soviet Economic System. Routledge & CRC Press, 14 Dec. 2024, https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781000881615_A45826316/preview-9781000881615_A45826316.pdf. (Accessed 03/07/2025)

- Hawkins, Charles. “From the Soviet Union to Russia: Changing Labor Conditions.” University of Northern Iowa, 1992, https://scholarworks.uni.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1150&context=draftings#:~:text=Officially%2C%20unemployment%20did%20not%20exist,the%20use%20of%20economic%20planning. (Accessed 05/05/2025)

- McCauley, Martin, and Dominic Lieven. “Russia – The Gorbachev Era: Perestroika and Glasnost.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019, www.britannica.com/place/Russia/The-Gorbachev-era-perestroika-and-glasnost. (Accessed 03/08/2025)

- Norwich University. “Consequences of the Collapse of the Soviet Union.” Norwich University-Online, 2024,online.norwich.edu/online/about/resource-library/consequences-collapse-soviet-union. (Accessed 03/07/2025)

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Infra-Annual Labor Statistics: Unemployment Rate Total: From 15 to 74 Years for Russia [LRUN74TTRUM156N]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 7 Mar. 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LRUN74TTRUM156N. (Accessed 03/07/2025)

- Schmemann, Serge. “End of the Soviet Union; The Soviet State, Born of a Dream, Dies.” The New York Times, 26 Dec. 1991, www.nytimes.com/1991/12/26/world/end-of-the-soviet-union-the-soviet-state-born-of-a-dream-dies.html. (Accessed 03/08/2025)

- World Bank. Constant GDP per capita for the Russian Federation [NYGDPPCAPKDRUS]. FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2 July 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NYGDPPCAPKDRUS. (Accessed 05/05/2025)

- WorldOMeter. “Russia Population (2025 and Historical). https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/russia-population/. (Accessed 05/06/2025)

- “1998 Russian Financial Crisis.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1998_Russian_financial_crisis. (Accessed 03/08/2025)