By Will Childs and Grayson Moniz

In June 2016, the United Kingdom voted to depart from the European Union, a monumental decision known as Brexit. Although their actual departure would not happen until January 2020, it immediately disrupted the nation’s political and financial spheres. The UK had existed and functioned within an integrated European framework for several decades, benefiting from free movement, ease of trade, and coordinated economic governance. Brexit symbolized political segregation from the rest of the EU and a major shift in the nation’s economic proceedings. This structural realignment catalyzed major change in the nation, predominantly through two vital macroeconomic indicators: inflation and unemployment.

Prior to Brexit, the UK had a relatively stable economy. The Bank of England was responsible for low inflation and a decline in unemployment after the financial crisis of 2008. The decision to depart from the EU shocked the nation’s economy. The pound sterling declined immediately after the votes had been finalized and fell to a 31-year low compared to the US dollar [8]. The falling exchange rate made imports more expensive, raising prices for the consumer and elevating inflation [7]. While the headline unemployment was relatively unaffected by Brexit, labor market dynamics faced growing instability. Specifically in sectors like agriculture, hospitality, and healthcare, which rely on EU workers, shortages became predominant [4]. Additionally, new immigration rules and trade frictions made hiring and production more complicated for producers.

According to the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), Brexit had an “impact on trade overall” that “appears to have been broadly consistent with predictions so far, that on immigration much less negative (and perhaps even positive) and on investment somewhat worse” [7]. Overall, they found that the decision to leave the EU had even more severe consequences than anticipated. It is also important to note the context of the UK’s decision, as it happened around the time of global disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic, making it difficult to entirely understand the magnitude of the economic impacts. However, among the effects of the landmark decision, inflationary pressures and labor adjustments are very much visible, measurable repercussions.

This project looks at the impact of the Brexit decision on the inflation rate and unemployment figures in the UK through macroeconomic data. Analyzing these two factors in isolation will provide an understanding of how this decision affected consumer realities and labor dynamics in the United Kingdom.

Data Analysis

We used data from the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) to analyze how inflation and unemployment evolved in the period surrounding the Brexit referendum. Specifically, we focused on the short-term effects of the 2016 Brexit vote, rather than on the actual implementation of Brexit in 2020. We chose not to analyze the effects of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU because the first two confirmed UK patients with COVID-19 were diagnosed on January 29, 2020, just two days before the official exit on January 31 [1]. In this light, we focused on the impact of the Brexit referendum by analyzing the announcement shocks and the initial adjustment of the UK economy in response to the vote.

Figure 1 shows us that the UK’s annual inflation rate had been steadily declining since 2011, reaching a historically low level in 2015. In September 2015, it sat at about 0.2%, rising only slightly to 0.5% by December. These low levels were reflective of a broader period of post-recession stagnation and falling global commodity prices, caused by the 2008 financial crisis. However, following the official approval of the referendum in June 2016, we notice that the UK experienced a rapid increase in inflation—peaking at 2.8% in September 2017, a clear jump from pre-Brexit levels [5]. This sudden increase can be associated with the sharp depreciation of the British pound shortly after the referendum’s approval, which made imported goods much more expensive. Also, as the UK relies heavily on imported goods, the impact on consumer prices was almost immediate. Food, clothing, and fuel prices increased in this post-referendum period [8], which contributed heavily to this inflation spike. The reason for this increase in inflation was not rooted in domestic demand (e.g. British consumers changing their consumption behavior due to the announcement of the UK’s exit of the EU)—it was rooted in the depreciation of the British pound. The depreciation of the pound reduced the UK’s purchasing power (on global markets), which led to more expensive imports. This type of inflation, one that is driven by higher input costs rather than increased consumer spending, disproportionately affected lower-income households, who spend a larger portion of their salaries on the essential imported goods—such as food—that became more expensive post-June 2016. Inflation remained high throughout 2017 and 2018, averaging about 2.5% during this period, well above the Bank of England’s 2% target. We concluded that Brexit essentially acted as a shock to the UK’s price stability, because it introduced this inflationary pressure to the British economy that was tied to currency volatility and disruptions in international trade.

Figure 1

Point A — Brexit Referendum (June 2016)

Point B — UK’s first two patients test positive for COVID-19 (January 29, 2020) & UK’s official withdrawal from the EU (January 31, 2020)

Source: Office for National Statistics

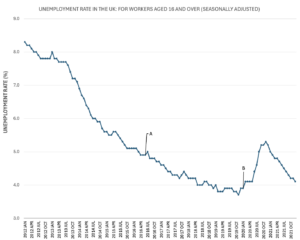

In contrast to this noticeable change in inflation, the UK’s unemployment rate remained a lot more stable. As shown in Figure 2, the unemployment rate was at about 5.2% in 2015 and dropped down to 4.9% in June of 2016, already after the official referendum approval [6]. In the months and years that followed the vote, unemployment rates actually decreased, reaching 4.3% in August 2017 and hitting a low of 3.8% in August 2019. These numbers suggest that the labor market was resilient in the face of uncertainty. However, while employment as a whole increased during this time, this employment growth was disproportionately concentrated in lower-paying jobs, such as retail or hospitality. Firms in these industries continued hiring, not because they expected no changes, but likely because demand for services remained steady and they anticipated a prolonged negotiation process before any legal changes to immigration and labor regulations would take effect. However, these jobs are, at the same time, very vulnerable to definitive changes in said laws. The reason why employment continued to increase was not because firms believed they would not have to let workers go later, but because the UK, as mentioned earlier, didn’t leave the EU until 2020, allowing non-British workers to keep their jobs during the 4-year period when no new immigration laws had yet been implemented. It is important to note that unemployment rose again after Brexit was officially enacted (Point B in Figure 2), as firms began to adjust to the new labor market constraints.

Figure 2

Point A — Brexit Referendum (June 2016)

Point B — UK’s first two patients test positive for COVID-19 (January 29, 2020) & UK’s official withdrawal from the EU (January 31, 2020)

Source: Office for National Statistics

Conclusion

Our analysis shows that the 2016 Brexit referendum had clear and measurable short-term effects on the British economy—a sharp rise in inflation caused by currency depreciation and a labor market that remained stable on the surface but that experienced several hidden vulnerabilities. It is evident from our data that the Brexit referendum disrupted economic stability and introduced new uncertainties that influenced prices and the labor market in the UK in the years that followed.

References

- Aspinall, Evie. “COVID-19 Timeline.” British Foreign Policy Group, April 8, 2025 (Last Edited). https://bfpg.co.uk/2020/04/covid-19-timeline/#:~:text=The%20UK’s%20first%20two%20patients,a%20specialist%20hospital%20on%20Merseyside. (Accessed 05/07/2025)

- Casey, Bernard. “The Labour Market Implications of Brexit – UK in a Changing Europe.” UK in a Changing Europe. February 25, 2025. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/the-labour-market-implications-of-brexit/. (Accessed 04/28/2025)

- David, Dharshini. “Is Brexit behind the UK’s Inflation Shock?” BBC News, June 21, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-65962027. (Accessed 04/27/2025)

- Davies, Rob, and Jack Simpson. “‘Arbitrary’ Election Pledges to Cut UK Migration Will Worsen Worker Shortages.” The Guardian. The Guardian, June 4, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/04/arbitrary-election-pledges-to-cut-uk-migration-will-worsen-worker-shortages?utm_source. (Accessed 04/27/2025)

- Office for National Statistics. “CPIH ANNUAL RATE.” Ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. January 15, 2025. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/timeseries/l55o/mm23. (Accessed 04/26/2025)

- Office for National Statistics. “Unemployment Rate (Aged 16 and Over, Seasonally Adjusted) – Office for National Statistics.” Ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. March 12, 2025. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/m. ((Accessed 04/26/2025)

- Portes, Jonathan. “The Impact of Brexit on the UK Economy: Reviewing the Evidence.” CEPR. Vox EU, July 7, 2023. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/impact-brexit-uk-economy-reviewing-evidence. (Accessed 04/28/2025)

- Treanor, Jill, Simon Goodley, and Katie Allen. “Pound Slumps to 31-Year Low Following Brexit Vote.” The Guardian. The Guardian, June 24, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jun/23/british-pound-given-boost-by-projected-remain-win-in-eu-referendum?utm_source. (Accessed 04/27/2025)