By Tatyana Avilova

From December 22, 2018, until January 25, 2019, the United States government shut down for 35 days, marking the longest government shutdown in U.S. history. The shutdown caused disruptions to the operation of several federal government agencies, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). One of the USDA programs affected by the shutdown was the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides benefits to eligible, low-income families to help supplement their grocery budget. In this post, I examine the impact of the government shutdown on SNAP participation and expenditure.

SNAP is funded by the federal government and is administered by individual states. Although the exact benefit distribution schedule varies by state, benefits are paid on a monthly basis, and each household receives their benefits on (approximately) the same day of every month.

Eligibility and the amount of SNAP benefits that a household receives is determined by various factors. For example, in Maine, household income should be below 200% of the Federal Povery Line for a household of a given size. The state “also look[s] at financial resources, assets, and certain expenses for [the] household” and “count[s] income from most sources including cash assistance, Social Security, unemployment insurance, and child support.” (State of Maine Department of Health and Human Services) Higher benefits are awarded to families with elderly and disabled household members.

Researchers find that SNAP households often face difficulties to smoothing consumption between benefit disbursement dates. For example, Hastings and Washington (2010) find that beneficiary households’ food expenditure decreases over the course of the benefit month, a pattern primarily driven by a decrease in the quantity (rather than quality) of purchases and higher retail prices at the start of the benefit month. Beatty and Cheng (2016) likewise find that food expenditure declines during the benefit month, with a decline in the unit cost of food. SNAP benefits typically do not cover a household’s food expenditures for the entire month, and beneficiaries need to use other sources of income or community assistance (e.g., food pantries) to cover the “end-of-cycle gap” in food expenditure.

In December 2018, SNAP beneficiaries received their monthly benefits on schedule, even after the start of the shutdown. They also received their January 2019 benefits on time. However, as the shutdown continued, faced with uncertainty about being able to support program beneficiaries, the USDA instructed states on January 8, 2019, to pay out the February monthly benefits before January 20 (US Department of Agriculture 2019 “USDA”). When the government reopened on January 25, states had already paid out the February benefits and would not be able to distribute the next benefits until March 2019, creating a disruption in the regular benefit payment schedule for most SNAP households. Given that these households already face difficulties to making their benefits last the entire month, a longer than usual gap between payments would likely create additional burden for them.

The purpose of SNAP is to assist the most disadvantaged members of the community. Understanding the impact of the shutdown on SNAP beneficiaries is important for policymakers to know how the impact of any future disruptions to the program can be managed to minimize harm to the most vulnerable.

Data Analysis

I analyze the impact of the shutdown on SNAP participation and expenditure using 2016-2019 monthly-level data from the USDA. I consider participation and expenditure both at the household and at the individual level: while benefits are paid out to households, some households have multiple members, so the number of persons receiving benefits will be higher than the number of households.

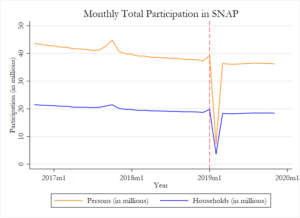

Figure 1

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, 2016-2019. Data is monthly.

Figure 1 shows total program participation. From December 2018 to January 2019, there was a small increase in the number of SNAP households, from 18.7 million to 19.8 million. During the same time, the number of individuals on SNAP increased from 37.3 million to 39.3 million. During the government shutdown, all non-essential government workers become furloughed, meaning they are put on a temporary leave of absence until the government is reopened. They do not receive income during this time. As these workers lost their incomes, some of them most likely applied for benefits, including SNAP.

In February 2019, program participation declined sharply, to 7.3 million. The beneficiaries who had already received their February benefits in January would not count as participating in the program in that month, accounting for the steep decrease. On the other hand, beneficiaries who had joined the program too late in January to also receive their February benefits in the same month, plus those who had only become eligible to receive SNAP in February, would be recorded as participating in the program. In New York City, some beneficiaries received their February benefits on January 17, while others received them at the regularly scheduled time in February (NYC Human Resources Administration). Participation recovered to levels comparable to those before the shutdown (18.3 million households and 36.4 million individuals) in March 2019.

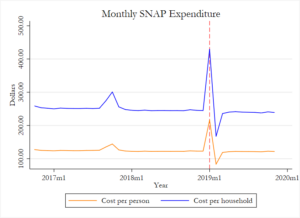

Figure 2

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, 2016-2019. Data is monthly.

Figure 2 shows monthly SNAP expenditure per person and per household. In constract to Figure 1, where we observe only a small increase in participation in January 2019, program spending per household and per person almost doubled at this time. Spending per household increased from $244.84 in December 2018 to $429.63 in January 2019, and spending per person increases from $122.74 to $216.44 over those months. This is consistent with the USDA announcement saying that they would pay out February benefits to program participants in January.

In February 2019, spending per household and per individual dropped sharply, to $167.34 and $83.45, respectively. Spending per household and per individual then recovered to pre-shutdown levels in March 2019, to $235.85 and $118.77, respectively.

Figure 2 suggests that the average SNAP household and individual received lower benefits in February 2019 compared to the benefits of participants in pre-shutdown months. SNAP benefits depend on various factors, like household size, income, saved assets, and other benefits that people in the household are receiving. The average SNAP household that applied to receive benefits at the time of the government shutdown (e.g., furloughed government workers) could potentially be wealthier than the average SNAP household in general, which would result in lower SNAP benefits by comparison. These beneficiaries may also receive higher average unemployment benefits, and some of them may also receive additional benefits from Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which all continued without interruption during the shutdown.

Conclusion

The U.S. government shut down for 35 days from December 2018 to January 2019. As a result, more people became eligible for SNAP in January 2019, and participation in the program dropped as households were paid their February benefits a month earlier. The households that did receive benefits in February 2019 were likely, on average, wealthier and received more benefits from other sources, compared to the average SNAP household. Future research might explore the characteristics of these households and also how consumption patterns changed for households receiving two-months-worth of benefits at the same time. Researchers may also study how reliance on other benefit programs and community resources, like food pantries, changed in response to the shutdown. This research will help policymakers to appropriately prepare for possible future disruptions to this and other programs.

References

- Beatty, Timothy K.M. and Xinzhe H. Cheng. 2016. “Food Price Variation in the SNAP Benefit Cycle.” Presented at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association.

- Hastings, Justine and Ebonya Washington. 2010. “The First of the Month Effect: Consumer Behavior and Store Responses”. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2(May 2010): 142-162.

- “Important Information for SNAP Recipients about your February Benefits”. NYC Human Resources Administration, Jan 2019, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hra/news/an-update-on-snap-benefits-for-february-2019.page. Accessed 15 Jul. 2020.

- “SNAP Data Tables”. United States Department of Agriculture, 8 May 2025, https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap. Accessed Mar. 2020.

- “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)”. State of Maine Department of Health and Human Services, 2023, https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/ofi/programs-services/food-supplement. Accessed 11 May, 2025.

- “USDA Announces Plan to Protect SNAP Participants’ Access to SNAP in February”. United States Department of Agriculture, 8 Jan. 2019. usda.gov/about-usda/news/press-releases/2019/01/08/usda-announces-plan-protect-snap-participants-access-snap-february. Accessed 7 Jan. 2025.