Why Implement Restorative Justice?

According to Libby Nelson and Dara Lind, “out-of-school suspensions have increased about 10 percent since 2000. They have more than doubled since the 1970s. Black students are three times more likely to be suspended or expelled than white students,” (Lind & Nelson, 2015). Besides the obvious distinction between the suspension rate of black students and the suspension rate of white students, another significant problem with these increased suspensions is the contribution to the school-to-prison pipeline. In the 1970s, suspension rates were very low, however, as the fear of increased violence in schools grew, the tolerance for the misbehavior of the students began to shrink (Lind & Nelson, 2015). Schools began implementing zero-tolerance policies, and at the same time, they also started to hire school resource officers to “protect the students.” In reality, these zero-tolerance policies became applicable to many offenses, such as talking back to a teacher or cheating on a test. Of course, the school resource officers began spending less time “protecting the students” and more time making arrests within the school walls. In fact, “about 92,000 students were arrested in school during the 2011-2012 school year, according to US Department of Education statistics,” (Lind & Nelson, 2015). Unfortunately, many of these arrests were made for minor misdemeanors or civil violations and 31% of those arrested were black students.

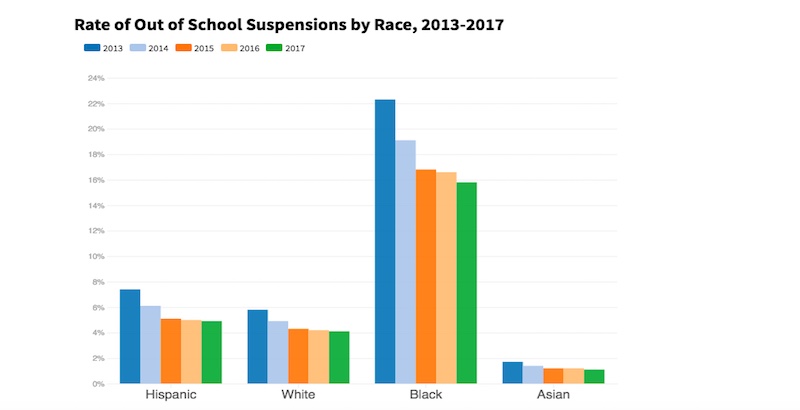

In California, despite the still present discipline gap between races, suspension rates declined between 2013 and 2017 with increased implementation of restorative justice. Koran, M. (2018, August 7). Even as California’s Student Suspensions Fell 46% Over the Past 6 Years, the ‘Discipline Gap’ for Black Children Remained as Wide as Ever. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from https://www.the74million.org/article/even-as-californias-student-suspension-fell-46-over-the-past-6-years-the-racial-discipline-gap-remains-as-wide-as-ever/

Obviously, zero-tolerance policies have only increased the number of suspensions in schools, while also enlarging the school-to-prison pipeline. Restorative justice techniques, however, have started to create solutions for ways to discipline students WITHOUT feeding this pipeline. The process of restorative justice includes implementing techniques to address the root of the behavior that has occurred, focusing on restoring the relationships that have been damaged. For example, instead of a student being suspended for fighting with another classmate, both students would go through restorative justice to discuss the problems that they have been fighting, aiming to specifically address the behavior and why it was wrong, rather than blindly punishing the student. Restorative justice methods have spread rapidly in the last decade and have been implemented in many school districts. Guided dialogues, training for teachers, as well as restorative justice leaders in schools have all produced many positive effects that have contributed to declines in suspension rates, as well as decreases in the suspension rate gaps between white students and minority students.

What has Denver Done?

In 1994, a group of Spanish-speaking elementary school students received unequal punishment from their peers. When a large group of kids in a Denver public school was punished for misbehaving, the Spanish students were forced to sit on the floor during lunch, while the non-Spanish-speaking students received a special table to sit at. Naturally, this did not sit well with the parents of these Spanish-speaking students, who participated in a year-long protest against Denver Public Schools. (Davis, 2019)

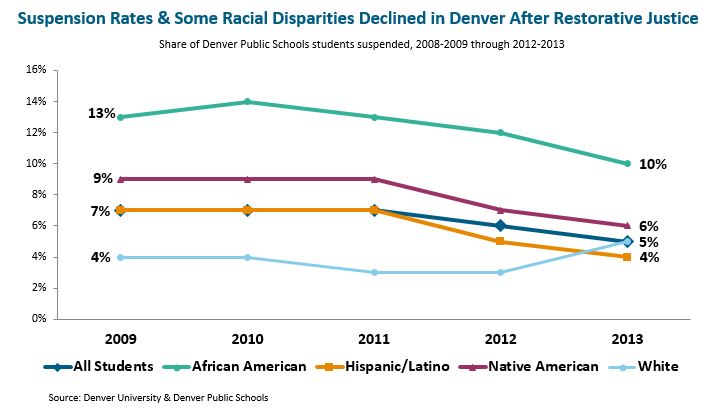

In 2006 Padres y Jóvenes Unidos combined with Denver Public Schools and the teachers’ union to create a restorative justice pilot program in four elementary schools. The program was implemented so successfully in the four elementary schools that restorative justice became part of official school policy at these schools, and Denver Public Schools successfully allowed for many additional schools to implement restorative justice into their disciplinary policies. The results speak for themselves: between 2006 and 2013, the suspension rate fell by about 47%, the suspension rate for African Americans fell 7 percent, the suspension rate for Latinos fell approximately 6 percent, and the discipline gap between African Americans and their white peers narrowed from a twelve-point gap in 2006 to just over an eight-point gap in 2013, a reduction of 33 percent. (Davis, 2019)

Learning Uninterrupted: Supporting Positive Culture and Behavior in Schools. (2017, April 3). Retrieved May 8, 2020, from https://massbudget.org/report_window.php?loc=Learning-Uninterrupted.html

A similar process occurred in the Denver Public Schools’ high schools. In 2009, Denver started implementing restorative justice practices in four public schools, including North High School. Nine years later, in 2018, more than 40% of Denver’s schools had staff trained in integrating restorative justice techniques into the disciplinary code. In 2010, 9,000 of 78,000 of the district’s students were suspended. In the 2017-2018 school year, less than 4,500 of 91,000 of the district’s students were suspended. As of 2018, teachers from all around the country have come to North High School to learn techniques and gather advice on how to implement restorative justice techniques in their own classrooms. Denver stands as a model for other cities in terms of their improvements made to their disciplinary code, focusing on restoring rather than punishing. (Asmar, 2018)