Katherine Cheston

Data:

Alaska, by land area, is the largest U.S. state. However, it has a low population density of less than 1.5 people per square mile. Thus, there are only approximately 130,963 students in Alaska’s public school system, and 6,032 Alaskan students attending private schools. As the state has such a low population density, most of Alaska’s public schools are rural schools; 58% of public school students in Alaska attend rural or small town schools (“Public Education in Alaska – Ballotpedia”).

Alaska’s average annual per pupil expenditure is $18,175 which is the second highest state per pupil expenditure in the United States. The average per pupil expenditure in the U.S. is $12,624. It makes sense that Alaska has a much higher per pupil expenditure as maintaining rural schools with small student bodies requires a higher per pupil cost. Alaska’s total state public education budget is about 2.5 billion annually (“Public Education in Alaska – Ballotpedia”).

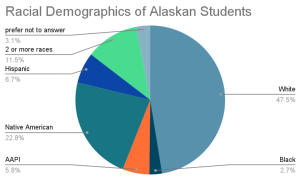

Below is a pie chart showing the racial demographics of Alaska Public School students. Less than half of the students in the public school system are White, and about a quarter of Alaska Public School students are Native American and/or Alaskan Natives. 10.32% of students are English language learners. The majority of English language learners in the U.S. are first or second generation immigrants, but in Alaska over 40% of the public school’s English language learners are Native Alaskans. Additionally, 34.77% of Alaska Public School students are on free or reduced lunch. This correlates pretty closely to the proportion of students living on or below the poverty line (“Data Center – Education and Early Development”).

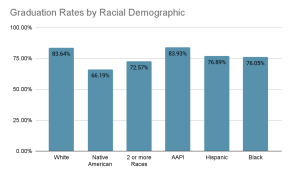

78.09% of Alaska Public School students graduate, which is less than the national graduation rate of approximately 86%. A chart of the graduation rates by demographic is included below. As you can see, the graduation rates for Native American students and students of two or more races are lower than the average. This is a disparity that Alaska Public Schools need to, and are trying to, address (“Data Center – Education and Early Development”).

As part of the new accountability system for Alaska’s public schools, schools are ranked on a five-point scale system (with 5 being the highest) called the Alaska School Performance Index (ASPI) which was implemented in 2013. The factors that weigh into these rankings are achievement (standardized test scores), progress (change in standardized test scores), attendance rate, graduation rate, and college readiness rate (ACT and SAT scores). I have many objections to this system as it is based mainly on standardized test scores. However, one thing ASPI has going for it is that it requires the schools to calculate subgroups of these scores for Alaskan Natives, Economically Disadvantaged Students, Students with Disabilities, and LEP (Limited English Proficient) students. Schools are ranked higher if their achievement gaps for these subgroups are smaller and/or closing (Alaska School Performance Index (ASPI) Worksheet Explanation).

Alaska has two standardized tests: The Performance Evaluation for Alaska’s Schools (PEAKS) which evaluate ELA and mathematics skills and The Alaska Science Assessment. Alaska has not yet adopted the Common Core or Next Generation Science Standards. The Alaska Science Assessment is a field test, so the only scores are participation rates. Unfortunately only 39.50% of students are proficient or advanced in ELA, 32.38% of students are proficient or advanced in Math according to the most recent PEAKS. These scores are low in spite of Alaska’s high per pupil expenditure. This can be interpreted many ways. Perhaps Alaska’s education funds could be better utilized, or perhaps rural schools just demand more per pupil funding. Another explanation could be that Alaska’s public schools need to do more to address racial, linguistic, ableist, and economic disparities. Another possible concern is that as Alaska has not adopted Common Core or Next Generation Science Standards so there are not enough curriculum guidelines for teachers, especially new ones (“NAEP State Profiles”, “Standards in Your State | Common Core State Standards Initiative”).

Teachers are relatively well paid in Alaska with an average salary of $68,120, and most teachers are part of the union National Education Association Alaska. Also there are not many charter schools in Alaska which often pay teachers less. Only 28 out of Alaska’s 507 public schools are charters and there are no school voucher programs in Alaska (“Data Center – Education and Early Development”, “Public Education in Alaska – Ballotpedia”).

Analysis:

Alaska’s public schools have the largest proportion of Native Americans of any state, which makes the public schools culturally diverse and presents great opportunities for place-based learning. However, having a large Native American population in public schools presents its own challenges that the Alaska Public Schools have often failed to meet. Approximately a quarter of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives do not know English when they enter kindergarten as many of them speak Yup’ik, Inuktitut, or other Native American languages at home and in their communities (“Alaska Native English Learner Students | REL Northwest”).

Most English as a Second Language programs are designed for first or second generation immigrants and not Native Americans. These programs, therefore, are not as effective as Alaskan Native centered programs that are designed for Alaskan Native English learners. And most school districts do not have English learner programs centered on Alaskan Natives. Therefore, more non-Alaskan Native English learners are proficient in English by seventh grade than Alaskan Native English learners (“Alaska Native English Learner Students | REL Northwest”).

This problem is compounded by the fact that there are higher proportions of Alaskan Natives in more rural parts of Alaska. Many of these small rural schools neither have the funding nor educators required for English as a Second Language programs. In addition, Alaskan teachers are rarely qualified to teach English as a second language as less than 6 percent of Alaskan teachers are Native Americans. Additionally, 80% of newly hired teachers in Alaska are from out of state and are not equipped with a great cultural understanding of Alaska (Hill).

Another issue is that Native Americans have faced systematic cultural genocide in the United States. This has led to economic disadvantages, and many of the Native Alaskan students (some of whom are English language learners) are also on free or reduced lunches. There is also a mistrust among Native Alaskan communities towards U.S. schools, due to generational trauma from so many Native American children being kidnapped and placed in boarding schools up until the 1970s. This may be a contributing factor to the low (66%) graduation rate for Native American students.

Alaska’s public schools have worked to address these issues. Many school board members in rural Alaska towns are Native Alaskans and are well aware of these disparities and inequities (Hill). Many of Alaska’s school districts have been asking themselves: How can Alaska Public Schools address the historic marginalization or the Native American and Alaskan Native communities? How can they do this in a way that makes the public school system more beneficial to these communities? How can public schools incorporate and grow from the rich culture of the Alaskan Native communities in their districts?

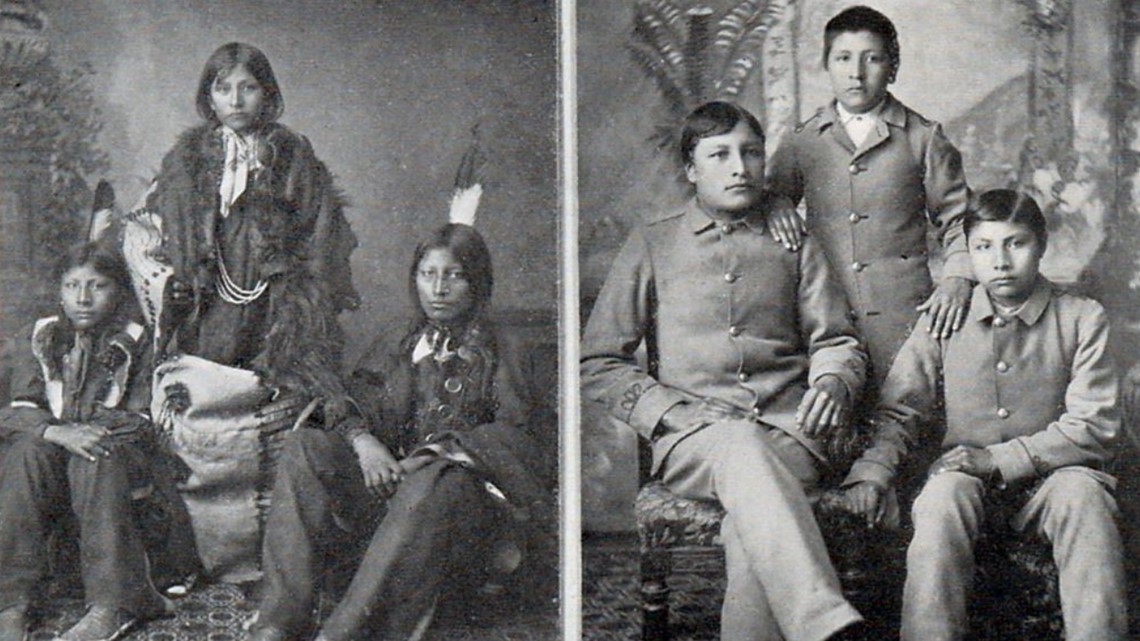

Some historic context is helpful to better understand the importance and complexity of these questions. In the late 1800s, Richard Pratt started the first boarding school for Native Americans. The goal of this boarding school and its successors was to “kill the Indian, and save the man”. It was systematic forced assimilation of children into Euro-American culture (Al Jazeera English).

These boarding schools were at first privately run by Christian denominations. However, the U.S. government soon started running their own schools and forcing Native Americans to send their kids there. Often those children never saw their families again. Many children died from the poor conditions, maltreatment, and lack of medical care in the schools. Many were buried in unmarked graves so their families never even got their children’s remains (Al Jazeera English).

Those that survived were traumatized as they had been forcibly removed from their families, dehumanized, physically harmed, and often sexually assaulted by the faculty at the schools. Additionally, the schools were often successful in removing Native American children from their cultures. Many Alaskan Natives were taken to boarding schools in the lower part of the U.S. never went back to Alaska. In all of these schools, children were made to wear Euro-American clothing and be called by numbers or “English” names. And as it was the point of the schools, children weren’t allowed to speak in Native American languages or carry on cultural customs or traditions (Al Jazeera English).

This has led to massive cultural and language loss, generational trauma, and a mistrust of schools with Eurocentric curriculum among Native American communities.

There has been grassroots efforts in many Alaskan public school districts not to only recognize Alaskan Native history and culture in school curriculum, but to teach through Alaska Native heritage. On a state level, Alaska has created standards for culturally responsive schools which include a focus on community and participating in activities that utilize traditional ways of learning (Alaska Standards for Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools Cultural Standards For: Cultural Standards For).

There are many great examples of how this cultural and place-based learning has been implemented throughout Alaska. The Lower Yukon School District started this 2021-2022 school year with two weeks of subsistence activities including walrus hunting. The students then made a short documentary linked below. Walrus hunting may not seem like a school activity from a western perspective but it’s a culturally relevant field trip in the outdoors and a subsistence life skill in Alaska. It’s an activity that not only makes school fun and exciting, but also helps make Alaskan Native students feel like their culture is being recognized instead of marginalized (Galvez).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zRLPpUCPJFY&t=13s

Other schools have incorporated Yup’ik or Inuktitut into their language curricula. Elders from the surrounding communities volunteer to participate in these programs as over 94% of Alaskan teachers are not Native American let alone fluent in Yup’ik or Inuktitut (Breen).

St. Mary’s School District has incorporated place-based learning into their STEM curriculum especially. Students collected data while berry picking and fishing to later use in experiments and projects (Breen).

Not all Alaskan schools are incorporating place based and cultural learning, and there is a lot of room for improvement in Alaskan schools. That being said, it’s really exciting to see how enriching place-based learning can be for all students. It is especially important in communities with such a rich Native American culture that should be to be valued instead of marginalized. Hopefully, these changes will help make Native Alaskan students feel more engaged and supported in their schools and lead to improved academic outcomes and graduation rates.