Does Georgia Serve all Students?

Does Georgia Serve all Students?

Julia DeLuca

Basic Data:

- 1,686, 318 students attend Georgia’s public schools (“Quick Facts” 2022)

- The Georgia Department of Education has a $9.9 billion education budget (Suggs 2018)

- The average per-pupil expenditure is $10,769 which is lower than the national average of $12,624 (Hanson 2022)

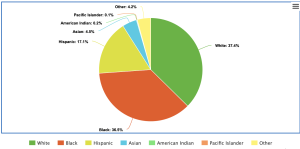

Georgia Schools Demographics

- 18.5% of children under 18 live in poverty (“Center For” 2022)

- In 2019 Georgia’s high school graduation rate was 82% (“Georgia’s 2021” 2022)

- This number falls to 58% for English Language Learners (2018) (“US Department” 2020)

- By demographic… (2019) (“Public High” 2021)

- Black → 80%

- White → 86%

- Hispanic → 76%

- The average teacher salary in 2022 was $59,062 (“Public School Teacher 2022)

- Teachers in Georgia form the union “Georgia Association of Educators (GAE)” which is associated with the NEA

Georgia’s Limited English Proficiency Students

Data Analysis:

An inequity that persists in Georgia is school funding. There is a wide range between the least funded schools and most funded schools. While the average per-pupil expenditure in Georgia is $10,769, the least funded district is Bryan County which spends $9,070 per-pupil (Hanson 2022). Bryan County has a relatively large population and includes two cities: Richmond Hill and Pembroke . The highest funded county is Clay County, and they spend $19, 866 (McCann 2021). Their population is relatively small in comparison to Bryan County. The average funding per school in Georgia is lower than the national average of $12,624 (Hanson 2022). This inequity reflects the problem that persists by local districts funding schools as opposed to all the funding coming from the state. The consequence of insufficient funding is not having enough resources for high-need students. This is reflected in graduation rate statistics. While the average graduation rate for Georgia in 2019 was 82%, this number drastically falls for students with disabilities (“Georgia’s 2021” 2022). In the 2012-2013 school year, only 35.1% of students with disabilities graduated (Stirgus 2015). This is the third lowest graduation rate for students with disabilities in the US. As was mentioned in chapter 4 of “Common Ground”, “high-needs” students cost more. Since Georgia districts are underfunded compared to the national average, this could explain the low graduation rate for students with disabilities.

It appears that Georgia is addressing this inequity through its expansion of the state’s voucher program. For the past 14 years, Georgia has had a Special Needs Scholarship Program. In 2021, this program expanded to what is called the “504 Plan” or “Rehabilitation Act” (Stirgus 2015).This act allows students to qualify for a voucher with a broader range of conditions, like autism and alcoholism. The Rehabilitation Act also serves to cut costs and involvement, as the vetting process is much shorter now. The push for a bigger voucher program continued into 2022, when House Bill 60 and 99 were passed for $6000 state funded vouchers (Tagami 2022). Since these vouchers were funded by the state, the local districts were able to benefit because they still received the same funding, and now had fewer students attending their schools. The per-pupil funding in certain districts was able to increase. These vouchers served families making under 200% of the federal poverty level, foster care children, children of military families, and students with disabilities (Tagami 2022). While this is a step in the right direction to address the problem of inequity, the vouchers don’t cover the full tuition of most private schools. This leaves families with the responsibility of subsidizing the remaining costs. Another drawback is that there is an eligibility cap. Starting in 2022 with a cap of .25% of the student population and expanding to a maximum of 2.5% of the student population, the state will offer vouchers to at most 43,500 students. This number is not at all close to the number of students who might need it. There are 204,004 special education students in the state of Georgia (Tagami 2022). While it is clear that Georgia is trying to better serve all students of different needs, they are not quite there yet.

How Have Standardized Tests Impacted Georgia Schools?

- Georgia adopted the Common Core in June 2010 (“Review of Common” 2022)

- What is the Common Core?

- “The Common Core is a set of high-quality academic standards in mathematics and English language arts/literacy (ELA). These learning goals outline what a student should know and be able to do at the end of each grade.” (corestandards.org)

- What is the Common Core?

- Merit Pay: “Merit pay is the type of compensation a company uses to reward higher-performing employees with ongoing additional pay.” (indeed.com)

Impact of Merit Pay on Georgia’s Schools…

Teacher merit pay began in Georgia in 2011. This means that teachers’ salaries were partially determined by their “success” as teachers. The reason that Georgia implemented merit pay was because of a bigger initiative, the federal Race to the Top program. 50% of a teacher’s determined “success” was how well their students did on standardized tests (Strauss 2015). Georgia’s standardized tests based on the Common Core assessment are called the “Georgia Milestones”. While the merit pay initiative only began in 26 districts in Georgia, it was meant to reach all of Georgia’s districts by 2016 (Stewart 2011). Gwinnett County, a district serving 180,000 students, claims to have implemented merit pay as a way to celebrate “top-performing” teachers (“Performance-Based”). While encouraging teachers to better serve their students may be the goal of those who believe in merit pay, that is not always what transpires.

This is most certainly not the case of the Atlanta Public School System. In 2013, the Atlanta Public Schools superintendent, Beverly Hall, was indicted with racketeering among other charges, and eleven teachers were convicted for cheating on standardized tests (Strauss 2015). This occurred because teachers felt increasing pressure because of movements like No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top to have their students perform well on Georgia’s Criterion Referenced Competency Tests. Part of the pressure teachers’ felt came from not only the consequences of possibly losing funding if their school didn’t do well, but also the competition for Federal Grants. District superintendent, Beverly Hall, incentivized this competition through merit pay. An article from The Washington Post cites that “if a school achieved 70% or more of its targets, all employees of the school received a bonus. Additionally, if certain system-wide targets were achieved, Beverly Hall herself received a substantial bonus” (Strauss 2015). This system that Beverly Hall put into place rewarded teachers for standardized test success, and put their job in jeopardy for failing to meet requirements. Instead of merit pay being used to have teachers successfully help their students in and out of the classroom, it became a way to force teachers to only focus on standardized test performance.

As what can be assumed to be a reaction to this, Georgia created the Teacher Keys Effectiveness System in 2016 (“Teacher Keys” 2022). This system had three components: 1. teacher assessment on performance standards (TAPS) 2. professional growth 3. student growth. This new way of assessing teachers took the pressure off of standardized testing, and took more of a focus on individual evaluations. It would be interesting to see how this will affect Georgia in the future.