This website represents a culmination of research on grassroots activist work concerning school closure in four urban settings: Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia, and D.C. I created this website as a project for Urban Education, an education course at Bowdoin College, taught by Professor Doris Santoro and taken in the Fall 2014 term.

Please post any questions, comments, or additional information concerning this site, tweet @amybrownedu, or send an email to [email protected]. I would be happy to continue this conversation with others. Thank you. Amy

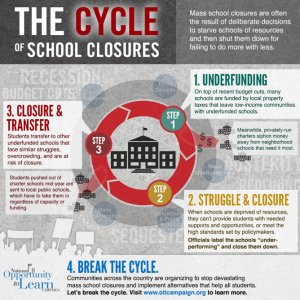

To assist in my explanation of school closure, I will use infographics created by the National Opportunity to Learn Campaign, featured on the Social Media page, and facts from a Rethinking Schools article on school closure, featured on the Professional Resources page.

Funding:P5

Funding:P5

Public schools are funded by federal, state, and local sources. In large, urban school districts serving many low-income students, resources are limited and schools that use funding “inefficiently” or are underenrolled are often targeted for closure proposals.

Testing/Performance:

Unfortunately, underresourced schools may not have the basic resources necessary to provide a quality education, such as support staff including librarians and counselors, curriculum materials, and school supplies. These schools are unable to adequately prepare students for standardized testing and students underperform. This provides further justification for policymakers to deem the school a failure and recommend that it is closed.

Privatization/Neoliberalism:

The struggle to maintain public institutions is a live issue in school closure decisions because displaced students need to attend a different school. Often, the new school is a privately-run charter school. Public school districts and school boards offer the possibility for community input in school decision making, even if that possibility is not always realized; charter schools are run by appointed boards of directors that do not hold accountability to a larger public. Therefore, school closure often represents the loss of public space.

Racial Targeting:P6

Racial Targeting:P6

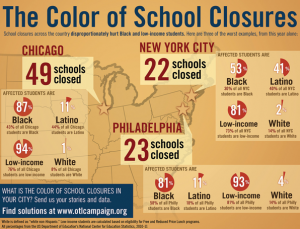

Low-income communities of color are most often affected by school closure. To the right, the infographic describes the demographics of students affected by school closure in three major cities. “Ten cities, including Philadelphia, Chicago, Newark, and New Orleans, recently filed civil rights complaints with the U.S. Department of Education about the disparate racial impact of school closures.”1 This is yet another instance of

education policies that unreasonably

disadvantage poor students of color.

Educational Outcomes:P7

Educational Outcomes:P7

Many of the justifications used to close the public school (underperformance, inefficiency, “failure”) remained unresolved after the school closure. “Numerous studies find no significant difference in academic quality between closing schools and the new schools receiving displaced students.”1 In these instances, it is clear that these justifications hold little meaning or traction in reality and are simply used instrumentally in school closure decisions.

Financial Outcomes:

Closed schools are often claimed to be “inefficient,” particularly if the building itself is old or if the school is underenrolled. However, the process of school closure has significant costs including building a new building or preparing a building to accommodate the displaced students, possibly providing additional bussing to transport students to a school outside of their neighborhood, and the administrative tasks of transferring paperwork, teaching positions, hiring and firing, and moving materials, among others. “A 2012 Pew study of six school districts found that school officials frequently overestimate cost savings. In early May, Chicago officials admitted they may have overestimated savings from school closures by at least $122 million. Washington, D.C., reported that 23 school closings had not only failed to reap any savings, but had actually cost the district nearly $40 million.”1

Most Importantly, Human Costs:

Students: “The Urban Youth Collaborative followed students at 21 closing high schools in New York City. According to Weiss and Long, they found that ‘discharge and dropout rates ‘skyrocketed’ between the year a school was slated for closure and the year it closed,’ from 25 to 70 percent at one NYC high school, and from 33 to 55 percent at another. Chicago studies have noted increases in danger to children’s physical safety as they navigated new routes through unfamiliar neighborhoods. Chicago’s back-to-school planning this year required police escorts and more than $15 million in additional security costs.”1

Additionally, the students’ emotional and psychological toll of school closure is significantly damaging; from experiencing their schools labeled as “failing” (and likely assuming that to having their neighborhood school taken away through closure, to moving to a new school, to acclimating to a new student body and new teachers who may know the legacy of your schooling history. Some live questions remain for me: When a school is deemed “failing” and closed, to what extent do students hold responsibility for this (“I underperformed, and my school and classmates suffered.”)? And/or to what extent does that label transfer to the student (“My school is not good enough to stay open. My school is my community. I am part of the community. How can I be good enough?”)?

Teachers: Teachers often lose jobs or are moved to different school buildings leading up to and following school closures. Additionally, “mass school closings have become another means to ramp up the ongoing war on teachers and labor unions. Both Chicago and Philadelphia saw wholesale assaults on unions following mass school closings. Chicago’s mayoral-appointed school board pink-slipped almost 3,000 teaching and support staff while voting to double its investment in Teach for America recruits.”1

Community: When school closure occurs, the community loses proximity to valuable educational resources, job opportunities, support services housed in school buildings (in some circumstances), and voice in a significant public forum. School closure often demonstrates distrust (“this school is not suitable to educate these children; therefore, we need to close it”) and creates distrust (“this city does not support my family or my children”) between community members and city officials, school board members, politicians, and people in power.