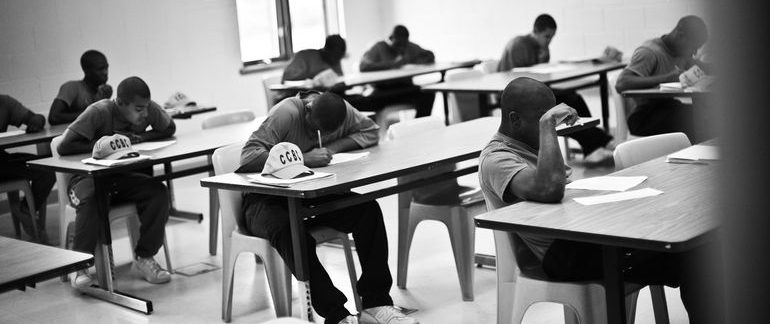

I chose this topic in part because of my own experiences in high school with zero tolerance. There were many instances during this research that I could recall how trivial, but at the same time volatile zero tolerance could be. I remember how administrators repeatedly belabored their mandate to exercise zero tolerance policies. Yet I also remember the faulty metal detectors that allowed a gun to be brought to my school. I remember when someone broke another students jaw in a fight in a cafeteria, yet was back at school in two weeks. And at the same time, I remember one of my friends getting expelled to an alternative school for selling mushrooms. If I gave my experiences with zero tolerance just one adjective, it would be inconsistent.

My initial perceptions of zero tolerance, aligned with many of the sentiments espoused by the students in the peer-reviewed article, the policies never felt equitable. Moreover I considered zero tolerance policies to be wholly black and white, either you receive the full punishment or not one at all. In some sense, if this were guaranteed I feel as though I could understand the parameters of the rules. Yet, as seen in my time at high school, equity and discretion muddled my understanding of rules as black and white into shades of gray.

Of course having discretion would not be necessarily an issue, yet these same rules failed to create consistency, which is crucial for one to understand the policies governing their school.

Grassroots organizing has more than just one type of group trying to actively engaging with the issue of zero tolerance. This can be seen through a organization having “the end to zero tolerance” as just one bullet point on a longer list of demands for education reform or it could be the focus of a program dedicated to that singular cause piloted in a community. However at the same time as some are actively trying to rouse society to the betterment of a socially progressive cause, there are those that would try and profit off of the movement be it through fear mongering or deceiving the public into interests ultimately aimed not at solving the issue. It is important to evaluate who you would advocate as a leader versus who is trying to industrialize the processes of education.

Grassroots organizing also continues to hold what I have felt from the beginning, a loose definition. Some groups can be as small as a group of students and faculty holding a weekly dialogue in a classroom, while others can combine with other organizations to create a national coalition that has the capital to lobby and establish widespread campaigns. Though it certainly can be considered cliché, I have further found myself realizing that grassroots initiatives start with people similar to myself. These people despite similar or worse off circumstances to myself are so passionate about an issue that they would devote their time and energy in earnest to make a difference regardless of the extent of its impact. It is a goal of mine to drive myself to similar ends.

I am a product of Urban Education, and through this course as well as previous and future courses I have found myself understanding and reflecting on my educational experience in a new way. I recognize more and more the privileges that I was given by the upbringing and persistence of my parents.

Urban education has proven like much of my study of education as being a difficult dissection of what is truly the best way to educate students. Though I feel most if not all Americans recognize the value of education, urban education has shown itself to me to be yet another battleground that is waged between the rich and poor. If education is the path to knowledge and knowledge is power then that power has constantly been safeguarded through institutions that uphold those who have had it the longest, knowingly or unknowingly.

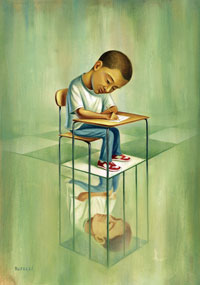

Also with my evaluation of zero tolerance I realized there persist justifications for its continuance. One that sticks out is the story of the bubble gun ending in a suspension for a student. It is easy to dismiss this as uncommon to the normal implementation of zero tolerance, however it does keep the controversy of zero tolerance alive. Yet by the media portraying failures of zero tolerance through “absurd” or “rare” occurrences, it silences the depth of the issue. Racial bias and inconsistency of implementation in public schools retain uncertainty and promote the eventual consequences of a school to prison pipeline.

Buzelli, Chris, School to Prison-Pipeline Image, 2013, Image , Retrieved From http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-43-spring-2013/school-to-prison

Urban education frequently has in place these obstacles that would continue to keep racial boundaries in place, which I saw through zero tolerance. For example, by advocating zero tolerance and its failure in media it provides justification for parents to exit public schools for the failure to keep their children safe while at the same time those unable to leave their schools are subject to the detrimentally flawed policies.

In short, this project has shown me that the addressing of issues through grassroots is one of the strongest reasons to maintain faith in American education as a whole. The power dealt to the people is commonly undervalued as many can point to high profile lobbying of conglomerates or corporations as the only real catalysts of change. Yet, the collectivization of groups especially under national coalitions show that effects of grassroots can be just as if not more impactful.