Children benefit when parents are involved in schools, but cultural and linguistic differences affect parents’ ability to comfortably engage. Corey Mitchell and Kate Stoltzfus discuss the challenges that minority and immigrant parents face. They identify possible solutions, stressing school-parent communication that values cultural difference. Mitchell focuses on the Latino parents of English Language Learners (ELLs), while Stoltzfus focuses on minority and immigrant parents in general.

Problem

Both authors identify a disconnect in communication between schools and immigrant or minority parents, as parents are less likely to talk with their children’s teachers due to intimidating linguistic and cultural barriers (Stoltzfus, 2016). Cultural differences may affect how Latino parents perceive communication with schools. For example, because “in some Hispanic cultures, parents view teachers as the experts and defer education decision-making to them,” they may feel less welcome at open houses and parent-teacher conferences (Mitchell, 2016).

Further, Mitchell and Stoltzfus both point out the troubling trend that teachers tend to contact minority and immigrant parents only with news of their children’s academic or behavioral issues. This “can be discouraging for parents for whom language is already a barrier to school participation and engagement” (Mitchell, 2016).

Significance

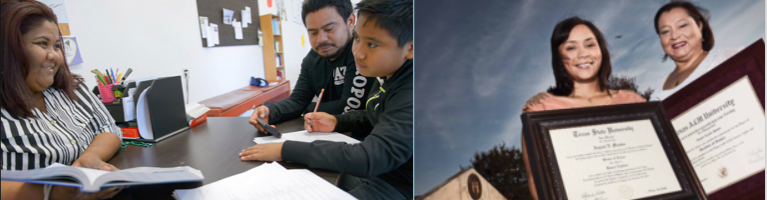

Improved parent-school communication should be a priority, as it can benefit child educational development. Stoltzfus (2016) believes that parents and teachers form “valuable partnerships” that enable better understanding of students’ needs both at home and in school. Mitchell (2016) focuses on Latino immigrant parent engagement, citing a study that suggests that engaging ELL students and parents simultaneously counteracts the “poverty trap” brought about by limited English skills. In this way, parent engagement proves a worthwhile pursuit, capable of improving “the academic and educational well-being of both generations” (Mitchell, 2016).

Solutions

Mitchell and Stoltzfus agree that communication needs to be strengths-based in order to bridge the school-family gap. In other words, teachers must confront biases, learning to view cultural difference not as a deficit, but as a strength. Latino parents have “gifts” to offer teachers, unique values and insights into student lives (Mitchell, 2016). Stoltzfus (2016) proposes that teachers undergo extra training in order to implement this strengths-based communication.

Stoltzfus (2016), however, also suggests that parents communicate with teachers to “stay up-to-date on classroom activities and ask for feedback about their children’s work and behavior.” While this advice may be useful, it fails to account for the linguistic barriers that many Latino parents face when dealing with schools.

Mitchell (2016) points out how discouraging these barriers can be, making it all the more important that schools take steps to make parents comfortable. Mitchell (2016) cites Washington Elementary, which keeps its library open to parents before and after school hours and employs an “open-door policy” so that parents feel welcome in their children’s classrooms. Mitchell (2016) also mentions teacher Christian Rubalcaba, who makes it a priority to conduct home visits for all his students, a strategy that can reduce intimidation and involve Latino parents in schools.