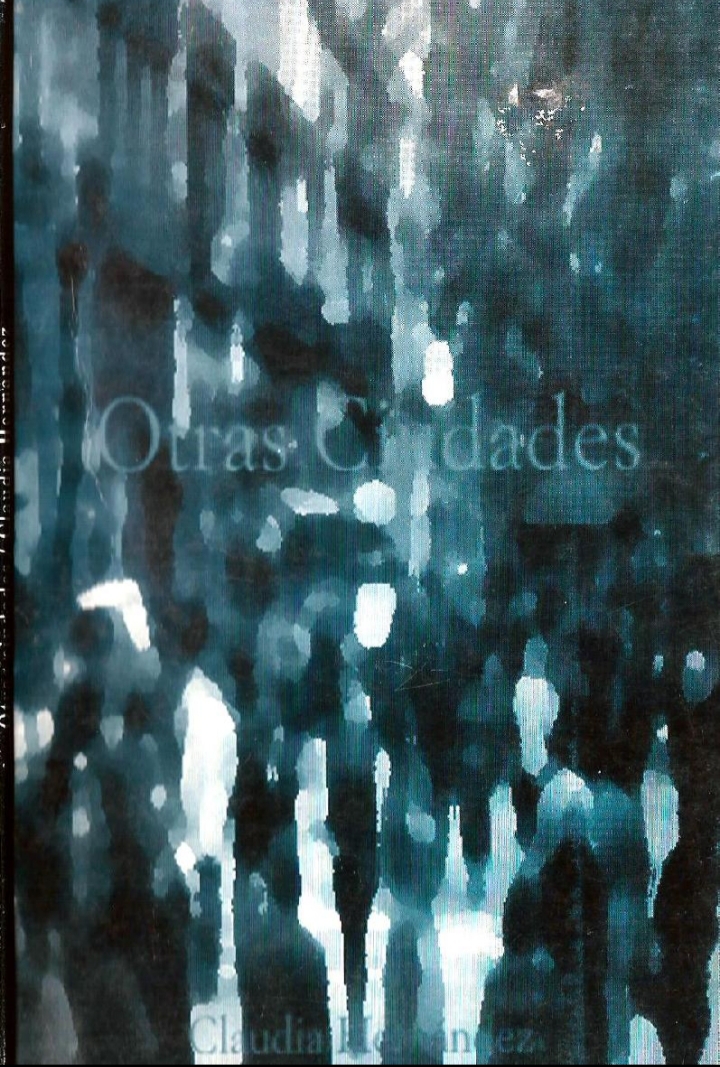

En una entrevista con el Stone Center for Latin American Studies, Claudia Hernández reveló que Otras Ciudades, una colección de catorce cuentos, surgió de una iniciativa humilde pero impactante. Ella escribió estos cuentos para un grupo dedicado a proporcionar libros a estudiantes universitarios que no podían costearlos. La intención de Hernández era abordar las preocupaciones prevalentes en el momento de escribir, alrededor del 2001, en la posguerra en El Salvador. La ciudad, como afirma Hernández, sirve tanto de musa como de telón de fondo para su narrativa. Cada cuento encapsula las incertidumbres colectivas de la comunidad. Al adentrarse en su obra, los lectores obtienen una visión de la profunda comprensión de la autora de las dinámicas sociales y su habilidad para traducir las experiencias comunitarias en narrativas convincentes. Las historias de Hernández no solo reflejan las ansiedades de una ciudad en posguerra, sino que resuenan con temas universales, invitando a los lectores a explorar las complejidades de la emoción humana y la resistencia.

Todos los cuentos están escritos en tercera persona. Sin embargo, la forma en que están narrados hace que los cuentos parezcan estar escritos en primera persona, como si estuviéramos dentro de los diferentes personajes. Parte de la razón se debe a la falta de estructura de las oraciones, lo que crea un flujo de pensamientos dentro de cada historia. Esto añade una capa de intimidad y cercanía entre el lector y los personajes. Es como si el lector estuviera dentro de la cabeza de cada personaje, experimentando sus emociones y pensamientos de manera directa y vívida.

Por ejemplo,“Empleo Temporal” se trata de alguien que le ha pagado a otra persona para que mate a otro. “No entrometerse, no ver, esperar, en veinte minutos habrán cesado de respirar y debe tomar el teléfono con guantes y llamar a la policía…” Esta oración es parte de una secuencia que sumerge al lector en la mente del asesino con un realismo crudo, mientras este se sume en una abrumadora reflexión sobre la moralidad de sus acciones. La falta de puntuación y la estructura suelta de las oraciones reflejan su caótico estado mental, creando un flujo continuo de pensamientos que revela su conflicto interno.

De manera similar, “Color del Otoño” es el segundo cuento de esta colección y contiene diez partes. Pesea a su división en secciones, en términos de oraciones carece de una estructura fija. Este cuento trata de una epidemia de suicidios de “Margaritas”. Cada parte comparte diferentes puntos de vista de los personajes, pero es difícil saber quién está narrando exactamente o desde qué punto de vista, ya que no hay nombres, aunque es evidente que cada sección corresponde a una perspectiva diferente. “Llamamos a la puerta, pedimos hablar con ella, verla, pero no quiso recibirnos” es un ejemplo de la estructura de la oración que ilustra esta técnica.

Hernández deja que las historias fluyan de manera natural, como si las narrasen en tiempo real por los personajes. Esta fluidez contribuye a la autenticidad de las experiencias narradas y hace que las historias sean aún más impactantes y resonantes para el lector. Además, esta estructura también hace que la lectura sea rápida debido a su fluidez y capacidad para cautivar al lector. Sin embargo, debido a esta falta de puntuación, a veces puede resultar complicado saber quién está hablando, detalle que añade encanto al ritmo vertiginoso del pensamiento y sumerge al lector aún más en la experiencia narrativa, invitándolo a interpretar y sumergirse en el mundo interior de los personajes.

Cuando le preguntaron sobre la estructura de sus cuentos en la misma entrevista, Hernández compartió, “Y eso que tú llamas falta de signos de puntuación es la gente interrumpiéndose mientras están hablando y lo que a veces se puede percibir como una como un cambio de dirección es el mismo temor hablando. Cuando el temor está en acción evade muchas, muchas de las reglas gramaticales. Es un método de supervivencia.”

In an interview with the Stone Center for Latin American Studies, Claudia Hernández revealed that Otras Ciudades, a collection of fourteen short stories, emerged from a humble but impactful initiative. She wrote these stories for a group dedicated to providing books to university students who couldn’t afford them. Hernández intended to address the prevailing concerns at the time of writing, around 2001, in the post-war period in El Salvador. The city, as Hernández states, serves both as a muse and a backdrop for her narrative. Each story encapsulates the collective uncertainties of the community. By delving into her work, readers gain insight into the author’s deep understanding of social dynamics and her ability to translate community experiences into compelling narratives. Hernández’s stories not only reflect the anxieties of a city in the post-war period but also resonate with universal themes, inviting readers to explore the complexities of human emotion and resilience.

All the stories are written in the third person. However, the way they are narrated makes the stories feel as if they are written in the first person, as if we are inside the different characters. Part of the reason is the lack of sentence structure, which creates a flow of thoughts within each story. This adds a layer of intimacy and closeness between the reader and the characters. It is as if the reader is inside each character’s head, experiencing their emotions and thoughts directly and vividly.

For example, “Empleo Temporal” is about someone who has paid another person to kill someone else. “Do not interfere, do not see, wait, in twenty minutes they will have stopped breathing and you must take the phone with gloves and call the police…” This sentence is part of a sequence that immerses the reader in the mind of the killer with raw realism, as he engages in an overwhelming reflection on the morality of his actions. The lack of punctuation and loose sentence structure reflect his chaotic mental state, creating a continuous flow of thoughts that reveal his internal conflict.

Similarly, “Color del Otoño” is the second story in this collection and contains ten parts. Despite its division into sections, in terms of sentences, it lacks a fixed structure. This story is about an epidemic of suicides among “Margaritas.” Each part shares different characters’ points of view, but it is difficult to know exactly who is narrating or from which perspective, as there are no names, although it is evident that each section corresponds to a different perspective. “We knocked on the door, asked to speak with her, to see her, but she didn’t want to receive us” is an example of the sentence structure that illustrates this technique.

Hernández allows the stories to flow naturally, as if narrated in real-time by the characters. This fluidity contributes to the authenticity of the narrated experiences and makes the stories even more impactful and resonant for the reader. Moreover, this structure also makes the reading swift due to its fluidity and ability to captivate the reader. However, due to this lack of punctuation, it can sometimes be difficult to know who is speaking, a detail that adds charm to the fast-paced flow of thought and immerses the reader even more in the narrative experience, inviting them to interpret and delve into the characters’ inner world.

When asked about the structure of her stories in the same interview, Hernández shared, “And what you call a lack of punctuation marks is people interrupting each other while they are talking, and what can sometimes be perceived as a change in direction is the same fear speaking. When fear is in action, it evades many, many grammatical rules. It is a survival method.”