In its totality, the Romanian Holocaust was marked by different, yet all horrific, categories of slow violence. The dehumanization of the Romanian Jewish population which occurred over nearly two decades. Romania’s Final Solution marked the Jewish community as a group of second-class citizens unnecessary to fulfill Ion Antonescu’s vision for a racially “pure” Romania. Finally, Romania’s plan to extort the Jewish community to deport its own citizens equated human lives with monetary value, as one might do with resources, exports, or other goods. As such, the horrors of Vapniarka were magnified by the different manifestations of slow violence during the Romanian Holocaust: the historic, the economic, and the political.

When I wrote this piece, I concluded that by itself, Vapniarka, and the relatively dramatic (and immediate) impacts of neurolathyrism, might mostly be best categorized as a spectacle disaster. But within the context of the Holocaust, especially the vast scale with which European Jews (amongst others) were murdered, it seemed that the Holocaust could not simply be categorized as a spectacle disaster: the deliberate othering and ethnic cleansing of Jews suggested, at least in part, that the Romanian Holocaust had aspects of slow violence.

As was common across Europe, the 1920s and 1930s marked a increase in laws and regulation meant to dehumanize the Jewish population. The Romanian government began conducting all government, business, and educational affairs in Romanian, alienating German-speaking Jews (Hirsch and Spitzer 2019, 17). Romanian (non-Jewish) nationals were prioritized for jobs, and Romania became less tolerant of other cultures; “Jews were relegated to the status of Romanian “subjects,” not “citizens,”” (Hirsch and Spitzer 2019, 17). Most seriously, “the increasing restrictions, quotas, discriminatory exclusions, harassment, and violence that Jews came to face and endure under Romanian rule” were evidence of growing danger facing the Romanian Jewish community (Hirsch and Spitzer 2019, 17).

These facts of life for the Romanian-Jewish community were not slow violence in of themselves; however, I believe that their presence in the Romanian psyche normalized political and economic exploitation that eventually enabled military leader Ion Antonescu and his regime to engage in slow violence against the Jewish people.

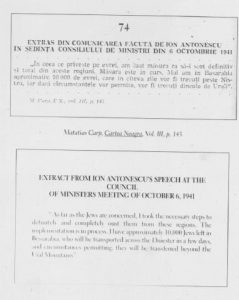

Romania’s foreign affairs played a role in the increase of Romanian nationalism, which exacerbated the antisemitism afflicting Romania’s Jewish community. By 1940, Romania was compelled by the Soviet Union to cede large swaths of land to the Soviet Union, followed by Hungary and Bulgaria (Braham 1998, 12). In response, “Romanian anti-semites, including elements of the Romanian army, vented their anger against the Jews, blaming them for their national misfortunes” (Braham 1998, 13). As such, in September 1941, Antonescu ordered that Jews from the Bukovina and Bessarabia regions (previously ceded to the Soviet Union), be deported to the Romanian-occupied Transnistria region (now in modern day Ukraine) (Braham 1998, 20). A 1941 telegram in which Antonescu described this process can be found below. It reads:

EXTRACT FROM ION ANTONESCU’S SPEECH AT THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS MEETING OF OCTOBER 6, 1941

“As far as the Jews are concerned, I took the necessary steps to [unintelligible] and completely oust them from these regions. The implementation is in process. I have approximately 10,000 Jews left in Bessarabia, who will be transported across the Dniester [into Transnistria] in a few days, and circumstances permitting, they will be transferred beyond the Ural Mountains” (From The Nizkor Project).

Beyond denoting Transnistria as a primary location of deportation for Romania’s Jewish population, this telegram also reveals another crucial aspect of the Romanian Holocaust: their implementation of the “Final Solution,” Adolf Hitler’s plan to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population. Ion Antonescu was explicit about his intentions with Romania’s Jewish population: he wanted them either to be expelled beyond Romania’s borders, or murdered (Solonari, 2017). In reference to Romania’s Final Solution, he remarked “I will have achieved nothing unless I cleanse the Romanian Nation. Because the borders do not make the strength of a nation, but the homogeneity and purity of its race” (Antonescu in Braham 1998, 21). It seems that here, Antonescu is focused primarily on the “purity” of the Romanian public—he doesn’t seem to particularly care what happens to Romania’s Jewish population, so long as they are not within Romanian borders. This explicit disinterest in the welfare of Romania’s Jews has similarities to Rob Nixon’s description of “surplus people,” who are “deemed superfluous to the labor market and to the idea of national development and…forcibly removed or barred from cities” (Nixon 2011, 151). While Nixon defines surplus people as mostly women and children, and approaches slow violence from an economic perspective, it seems as though the Jews of Romania were forced into a similar situation, politically. As described above, Antonescu did not include the Jewish population in his vision for a “pure” Romania, and had no qualms about barring them from Romanian cities (although it should be noted that in comparison to Nixon’s definition of surplus people, in Vapniarka, as was common in many concentration camps, the prisoners were expected to perform manual labor) (Enneking 2015, 4). As such, the Romanian Jewish community’s status as political surplus people suggests that the Holocaust was a manifestation of a politically motivated slow violence.

Starting in 1942, however, the slow violence of the Romanian Holocaust developed another characteristic: economic. The relationship between the Antonescu and Nazi regimes was fraying, and the mass murder of Romanian Jews was becoming less appealing (Ioanid 2000, 243). As such, Romanian officials devised a new plan to rid Romania of its Jews: repatriation, for a fee. For example, the plan proposed that “a group of three thousand Jews among those slated for deportation to Poland might be allowed to emigrate to Palestine in exchange for two million lei” (Ioanid 2000, 244). Likewise, in April 1943, “talks about repatriating the orphans continued, focusing on how much to pay in taxes per child” (Ioanid 2000, 251). Here, while the explicit murder of Romanian Jews was tapering to a halt, the exploitation of Jews was continuing, albeit in a different form. These Jews were assigned monetary values, exploiting their value as human capital, not just as a political byproduct of an “impure” ethnic state. Yet the survival of the Romanian Jews still depended on the whims of the Romanian government: they were still liable to be massacred if their economic value could not be fully exploited. As such, this economic manifestation of slow violence had similarities to the slow violence described by Nixon, where human lives were treated as akin to resources extracted from the Earth (Nixon 2011, 79).