Typhoon Nina

On July 29, 1975, a tropical disturbance started to form in the Philippine Sea and headed Northwest towards Taiwan (Annual Typhoon Report). This storm reached typhoon intensity on August 1st and continued into Taiwan, where it left 25 dead, 168 injured, and a sizable amount of structural damage in its wake (Annual Typhoon Report). The typhoon continued to China where it made landfall on August 3rd. Most southeast Asian typhoons tend to lose strength and dissipate soon after entering the continental mainland, but this was not the case with Typhoon Nina (Si).

The typhoon continued its course into mainland China, where it stalled over the province of Henan on August 5th after hitting a cold front (Si, Dam Failure). Henan province is situated between the Funiu and Tongbai mountains in the central plains of China, centered around the Huai River Valley (Si). The geography of the region, mountains enclosing a large plain created a large watershed all leading into the Huai River. At the time, there were hundreds of dams built to control flooding and retain water (Si).

Flooding and Dam Failure

As the rain began to fall in the region, the gates of most dams were kept closed to retain as much water as possible (Si). There had been a drought in the region for much of the summer (Si). Over the next three days, over 150cm/60in of rain fell in many parts of Henan province (Si). During the most intense parts of the storm, areas received seven inches in a single hour (Dam Failure).

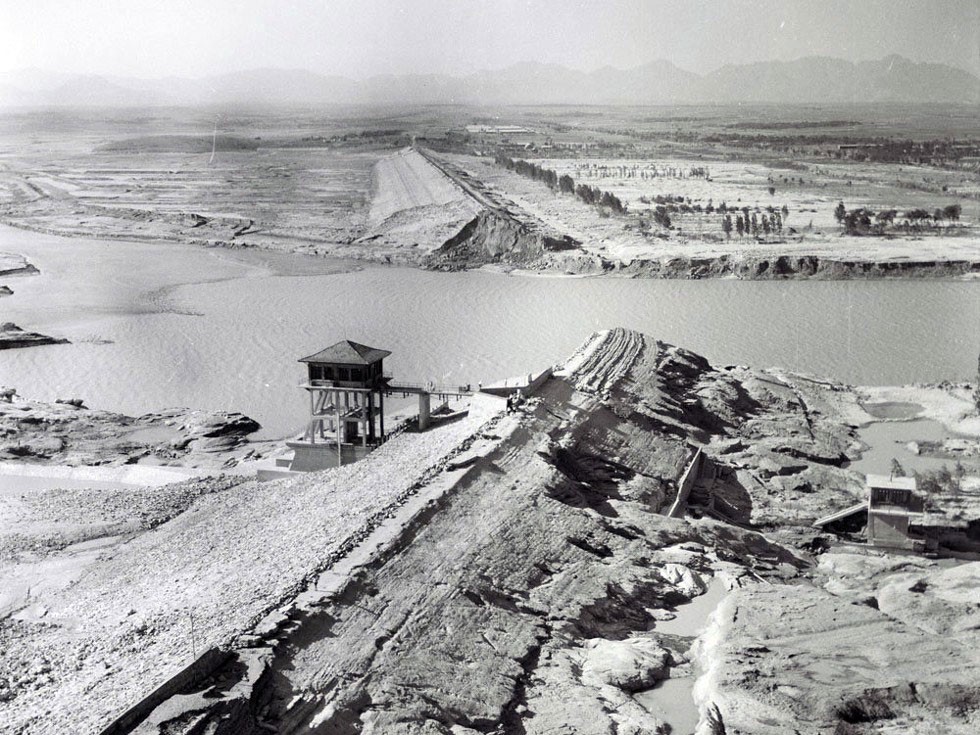

In the upper reaches of the Huai river system, on the Ru River, the Chinese built the Banqiao Dam in 1951. Built under Soviet supervision with a new design, “the iron dam,” and it was assumed to “be unbreakable,” even in the worst floods (Dam Failure). As rain fell throughout the region, many dams began to reach capacity and the reservoir management bureau tried to limit flood as much as possible. Typhoon Nina had disrupted the telephone connection to the Banqiao Dam, so downriver no messages were received it was assumed that the great dam had contained the floods (Si).

On the evening of August 7th, some smaller dams started to break below the Banqiao Dam. But dam workers furiously tried to shore up the other dams, trusting that the Banqiao dam would hold (Human Rights Watch). However, late that night on the seventh, floodwaters overtopped the Banqiao dam and the entire Banqiao reservoir began rushing down the Huai river valley (Dam Failure). The Chinese engineers had neglected to maintain or even removed flood mitigation measures to improve water retention and farmland access since the construction of the dams in the 1950s (HRW). This made it so the water continued to build and build as an increasing cascade down stream. In the torrent of water, there was a domino effect, water numerous smaller and mid-sized dams collapsed below the Banqiao dam added to the intensity of the flood. That night 62 total dams failed in the Huai river system (HRW).

Impacts and Aftermath

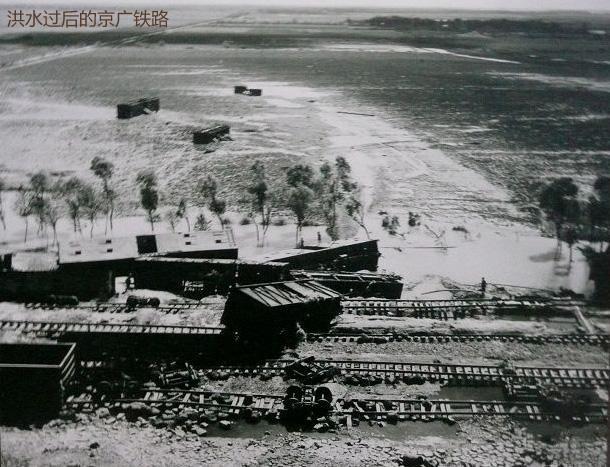

The impacts of the Banqiao and related dam failures were enormous. As the cascade of water tore through the province “it obliterated nearly everything in its path.”(HRW). Over ten million people were displaced, three million acres of farmland were destroyed, and 85,000 people died in the flooding (Si). In the city of Suiping, right along the Ru River, an estimated 200,000 people were overwhelmed by the flood and had to float through flowing water to survive (Si). The flooding destroyed sixty miles of the Beijing-Guangzhou railway, the primary rail system through the region (Si). Service was shut down for eighteen days and no cargo was transported for another thirty after that.

The recovery was a slow further disaster. Ten days after the flood began, 1.1 million people were still trapped by the water, disease was running rampant through the population, and most sources of food and shelter were destroyed (HRW). Medical and relief teams couldn’t reach most of the affected regions until two weeks after the disaster (HRW). So the Chinese government airdropped food and supplies in a haphazard manner, where “fifty to sixty percent of food supplies parachuted in by air have all landed in the water,” (HRW). All told, the death toll would increase to an estimated 230,000 as people in the region died from famine and disease (HRW). Across China and the world, no information was spread about the disaster. The only people who knew about it outside Henan province were within the “confines of China’s top party leadership and elite hydrological circles,”(HRW).