Pretty privilege saturates all aspects of TikTok. Individuals who are “TikTok stars” are often beautiful (I will be using the term “TikTok stars” to describe individuals who have attained their fame exclusively through TikTok and have over 20 million followers) TikTok stars often gain their following through videos that accentuate their physical features (usually their body and face) through dancing and  voice-overs. While many of the most popular TikTokers are famous due to manipulating their appearance, there are many renowned TikTokers who have established careers separate from TikTok. For instance, Will Smith (right), an American actor, producer, and rapper, has 40.8 million followers, and Jason Derulo (left), an American singer, songwriter, and dancer, has 39.1 million followers. Still, their fame came from avenues other than TikTok, such as television and music. I would not categorize these individuals as TikTok stars because of the talent they showcase apart from TikTok content. Not to be harsh, but most TikTok stars do not have exceptional talent. It is solely their appearance and aesthetic that is desirable to the viewers. They gain followers by smiling, dancing poorly, and flexing their abs, while individuals like Will Smith and Jason Derulo spend hours outside of TikTok producing original work. Don’t get me wrong, both Derulo and Smith gain many followers by smiling and flexing muscles, but they have an extensive portfolio of work that set them apart from the app, proving that their following is not solely based on their beauty.

voice-overs. While many of the most popular TikTokers are famous due to manipulating their appearance, there are many renowned TikTokers who have established careers separate from TikTok. For instance, Will Smith (right), an American actor, producer, and rapper, has 40.8 million followers, and Jason Derulo (left), an American singer, songwriter, and dancer, has 39.1 million followers. Still, their fame came from avenues other than TikTok, such as television and music. I would not categorize these individuals as TikTok stars because of the talent they showcase apart from TikTok content. Not to be harsh, but most TikTok stars do not have exceptional talent. It is solely their appearance and aesthetic that is desirable to the viewers. They gain followers by smiling, dancing poorly, and flexing their abs, while individuals like Will Smith and Jason Derulo spend hours outside of TikTok producing original work. Don’t get me wrong, both Derulo and Smith gain many followers by smiling and flexing muscles, but they have an extensive portfolio of work that set them apart from the app, proving that their following is not solely based on their beauty.

Don’t get me wrong, there are undoubtably TikTok stars who produce original content, but most of the content that fills TikTok stars’ pages are produced by a “nobody!” When a lesser-known TikToker makes quality content and receives some buzz, what do the beautiful influencers do? They take it. It goes viral. And the “nobody who produced the content? They are forgotten. While TikTok does provide the opportunity for TikTokers to give credit to producers of original audio (via a small feature in the bottom right corner), the platform does not require credit to be given to the producers of the content of the video. That means that TikTok stars do not have to give credit to the individuals who choreographed the dance or masterminded the trend they are doing in their TikTok, even when it is a direct copy of someone else’s post. Every so often, a TikTok star will put “d/c” (dance credit) in the caption of one of their posts, acknowledging the unoriginal content of their video, giving credit to the choreographer, but this infrequently occurs and only with dance TikToks. Once the post has been recreated enough times, credit often falls on the individual who is seen doing it the most: the beautiful TikTok star whose popularity sprinkles them throughout everyone’s “Discover” page. TikTok celebrities are stealing the content of others. No consequence.

You may be wondering “What’s the big deal? Who cares if they do not give credit?” The issue with neglecting to provide credit to original producers is that TikTok stars are making enormous sums of money on their posts. TikTok stars are turning a profit and not providing royalties to the original producers of the content. TikTok stars get most of their money through sponsorships directly influenced by followers and engagement rates. Jason Derulo makes quite a lot of money on Tiktok. When confronted about whether or not he makes $75,000 per TikTok video, Derulo states that he thinks “it’s tacky to say what I do make from them, but it’s far more than that. I’m not going to say what it is’”. The thought of making $78,000 per post is shocking! But his profits don’t come strictly from TikTok and sponsors. He receives royalties for many songs that have gone viral on TikTok, receiving money each time they are used. He is getting credit for the original content he creates!

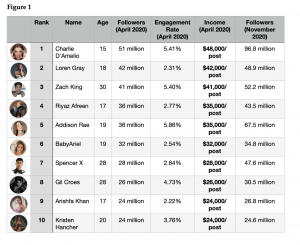

I created a chart that lists the highest-paid TikTok stars, titled Figure 1. Of the top ten earning TikTok stars, Zack King and Spencer X are the only producers of original audio and content. The other eight’s range consists of almost exclusively voice-overs and dancing music and audio producers by others. Zack King specializes in illusions, which takes so much time, effort, and money, and Spencer X is a very talented beatboxer, which must have taken him years to master. Given that these two individuals make up the third and seventh most profitable TikTok stars, TikTok seems to be rewarding the beautiful, not the talented. As of April 2020, the two creator’s of original content in the top ten earners account for only 20.6% of the total $335,000 per sponsored post earned by the top ten, whereas the remaining eight “pretty” TikTok stars account for 79.4% of the the total $335,000 per sponsored post made by the top ten (Figure 1). TikTok who are not considered hot or sexy must put in infinitely more effort and time into their content and are rarely financially compensated. Their content contains creative edits, helpful tips, or specific talents.

Meanwhile, pretty privilege allows beautiful TikTokers to be compensated with money, fame, popularity with minimal effort or time. Honestly, they do not even use creativity. They do their hair, put on some makeup, toss on a trendy outfit, and lip-sync. Some videos go viral of them just goofing off in front of the camera, gaining millions of views and hundreds of thousands of likes. Their laziness is rewarding not only socially but financially. Given that the data mentioned earlier was taken in April of 2020, the number of followers of each of the top TikTok stars increased. It is not super far-fetched to assume that so made their profits!

So you might be wondering, what’s the big deal? Who cares if these pretty kids are making a little money? Well, let’s unpack this. According to Daniel Hamermesh, an economics professor at the University of Texas in Austin, attractive people earn an average of 3-4% more which adds up to more than $230,000 in a lifetime (Shellenbarger). So there is a long history of beauty financially rewarding beautiful people. The financial benefits of being beautiful are manifesting themselves on TikTok.

Additionally, pretty privilege is allowing TikTok stars to steal the content of others. In academia, plagiarism like this has serious consequences. Trademarks, patents, and copyrights are all established to protect producers of original content from the effects of capitalism, ensuring profits are given to producers not reproducers of material. TikTok has gotten around all of these protections, allowing pretty privilege to flourish, costing “normal” TikTokers potential profits. Jason Derulo’s large income via royalties on TikTok is proof that financial compensation is available to producers of original content on TikTok. TikTok is rewarding appearance and not content. TikTok stars can take someone else’s content without giving credit to the original producers of that content, make it go viral, and profit from this popularity. The more famous they become, the more followers they acquire. TikTok stars receive more public engagement, they receive sponsors who pay them to endorse their products. Pretty privilege allows stolen content to go unchecked, robbing original and typically “not-as-beautiful” TikTokers of tremendous potential profits.

Given that TikTok is already such an established and popular social media platform, I am not sure how we could correct this theft and provide credit for producing the original. Ideally, I would hope that if brought to the attention of TikTok stars, they will begin to acknowledge the accounts who created the trend/content they are using in their videos, but I doubt that. Why would they change a system that is rewarding them for minimal effort? I guess my other hope would be that enough attention is brought to this issue that TikTok will be forced to add a requirement that users must acknowledge the use of content that is not theirs!

Again, the police broke up the party and issued them a second citation and court date. On August 19, the

Again, the police broke up the party and issued them a second citation and court date. On August 19, the  d caring. The halo effect means that fans who find Hall and Gray attractive have already colored their

d caring. The halo effect means that fans who find Hall and Gray attractive have already colored their