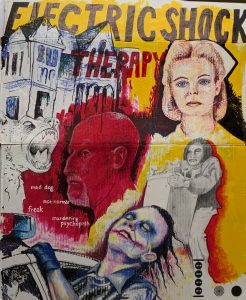

Madness on Cardboard represents an exploration into the roots of my subconscious stigmatization of severe mental illness (SMI), mental health treatment, and the role media plays in creating this stigma. Widespread research initiatives affirm the media’s significant influence on the stigmatization of SMI and mental healthcare (Edney, 2004). Analysis of film and print involving individuals with mental illness identify three salient themes that contribute to stigmatized attitudes towards mental illness: a fear-based perception of people with mental illness as homicidal maniacs, that those with SMI maintain childlike perceptions of the world, or that their mental illness stems from weak personal character (Corrigan and Watson, 2002). I portray my own stigmatized, fear-based perception of SMI artistically to uproot my hidden fears and find a more significant understanding of what creates such stigma.

Using a mixture of acrylic paint, oil pastels, graphite, and marker, I reflect on three highly awarded film and television depictions of individuals diagnosed with SMI and their healthcare providers. At age 13, I viewed the television program American Horror Story: Asylum. Despite its campy nature, the show’s horrific brutality solidified a traumatizing association with mental health care and violence. Years later, the narrative of the film The Dark Knight exposed me to the Joker: an individual with SMI portrayed as a criminal, animalistic, homicidal maniac. My education regarding the deinstitutionalization movement involved examining the 1975 film depiction of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. My decision to represent this film artistically examines how biases against SMI and mental health care often persist in society despite widespread public education regarding SMI (Link et al., 1999). Despite educating myself regarding the societal stigma mapped onto SMI, I wanted to examine the persistence of my inner biases despite this education and themes in the prolific film that contributed to societal stigmatization.

Completed on a white piece of cardboard, primary colors and black comprise the mixed media project’s color scheme. While the piece does not explicitly address childlike mapping stigmatization onto individuals suffering from mental illness, One Who Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest utilizes this theme in its plot. For example, the hospital transports its psychiatric patients on a yellow school bus and shapes the patient’s childlike portrayal in the film. The vibrant blue, red, and yellow of the piece inverts the childish nature inherent in the color scheme and binds it with themes of darkness ingrained in the black marker work. The oil pastel portraiture employs the same primary colors, thus tying together all three portraits’ identity in a shared state of insanity. Despite their different roles as criminals and mental health care professionals in their narratives, each character represents collective media narratives that impinge upon reality to demonize mental healthcare and mental illness.

Outlined in black in the upper corner, the prolific Nurse Ratchet stares emotionless into the distance. To her bottom left, red portraiture depicts criminal Dr. Arthur Adren, of American Horror Story: Asylum. Their positioning near Briarcliff Manor represents their connection with the flawed idea of mental health treatment, based on manipulation, violence, and control. The predominantly white portrait of Nurse Ratched maintains her mechanic, unfeeling exterior. Tinged red highlights subtly represent her manipulative, emotional violence, while the black marker work shrouding her image symbolizes her internal wickedness. Arden’s violence is far more apparent, consuming his identity as the “mad doctor.” Unlike Nurse Ratched, the dark outline around his face defines the portrait just as Arden’s internal evil defines his character. While Adren’s experimental “treatment” involving graphic surgeries of asylum patients lacks basis, in reality, the strong association between violence and mental healthcare creates a fear-based narrative, especially traumatic and distressing for younger, impressionable viewers attracted to the show.

The themes inherent, particularly in Arden’s character, exist in haunted asylums or straight jackets as Halloween costumes, all of which exploit stigmatized representation of mental illness and mental healthcare treatment with overtones of horror and brutality. Above the heads of Arden and Ratched reads the epitome of the stigmatization of mental health treatment: electric shock therapy. A central theme in any haunted asylum narrative is that the giant block letters command the viewer’s attention and evoke a feeling of discomfort. The red lettering of therapy summons unsettling feelings of violence as it coalesces with the murderous red used in both Ratched and Arden’s portraiture.

Depicted in both One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and American Horror Story: Asylum, the stigmatization of electric shock therapy, medically referred to as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), misrepresents its modern use in treating mental illness. The violent image of Randel P. McMurphy or American Horror Story: Asylum characters Lana and Jude receiving ECT criticized its early use from the late 1930s into the mid-70s in asylums such as Briarcliff Manor and the Oregon psychiatric hospital depicted in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. After receiving extensive ECT, McMurphy and Jude behave as if in comatose, suggesting that the treatment destroyed their cognitive abilities and true, human nature. Despite the factual accuracy of the past ECT abuse, the celebration and preservation of these narratives demonize ECT by presenting it as a central theme in horror stories that stigmatize mental health treatment and fail to represent the modern administration of ECT.

In reality, many psychiatrists use ECT as a highly effective treatment recognized by the American Psychiatric Association, the American Medical Association, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Present-day ECT involves trained medical professionals briefly stimulating the brain of an anesthetized patient with an electrical current. ECT treats severe mental illnesses, such as severe major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. The stigmatization of such treatment impacts patient treatment choice, patient consent, and provision of and referral for ECT (Griffiths and O’Neil-Kerr, 2019) that can potentially influence an individual’s access to ECT-aided recovery.

Positioned under nurse Ratched’s omnipotent portraiture, representing the power dynamic presented in the novel and film, Chief Bromden lifts the water fountain in his final escape scene from the psychiatric hospital. While Kesey spends time developing complexities and nuances in Bromden’s identity, the film falls short in its portrayal of his character. By failing to explain Bromden’s reasoning behind hiding his cognitive abilities, the film suggests “Chief” (as he is referred to in the film) is “faking” mental illness. This oversimplification of Bromden further contributes to the themes of “faking and pretending ” mental illness, ideas identified as mapping stigma on individuals with mental illness (Crumb et al., 2019). Furthermore, Bromden’s belief that he is weak and damaged further plays into the narrative that mental illness is the result of personal inadequacies instead of actual sickness.

Bromden represents the only central character of color in the film, yet he is drawn in black and white graphite. His colorless depiction speaks to the film’s failure to address the prevalence and reality of SMI in individuals of color. Native American populations are 2.5 times more likely to experience severe psychological distress (National Center for Health Statistics, 2017) and far less likely to access medical treatment (Gone, 2004). His red outline refers to his final act in which he kills a comatose McMurphy in a gesture of mercy, further shadowing mental illness narratives in themes of violence. In lifting the massive water fountain, Chief Bromden must overcome the weight of his racist film depiction, his oppression in the psychiatric facility, and his mental illness that Kesey describes in the novel.

Beneath Chief Bromden, the Joker, as portrayed in the film The Dark Knight, throws his head out of the window of a cop car. Regarded as the ultimate villain, actor Heath Ledger described the character as a “psychopathic, mass-murdering schizophrenic clown with zero empathy.” As the Joker, Ledger captures certain behavioral components of mental illness that demonstrate the “mad-dog” theme associated with the villain, an identity depicted above the Joker. The Joker’s tongue movements, a manifestation of tardive dyskinesia, and occasional growling further solidify this characterization. White words used to describe the Joker in the film connect the Joker’s portraiture and his mad-dog identity. These words further clarify the Joker’s stigmatized portrayal that characterizes individuals with SMI as inherently inhumane, unpredictable, dangerous, and criminal.

The embodiment of narratives disparaging mental health in the three highly acclaimed and popular television and film programs suggest my analysis might reflect stigmatization embodied not only in myself but in the American public. This artistic recording of enhanced self-reflection and following academic analysis represent the importance of unrooting inner stigma against mental illness within the general public, academia, law enforcement, and most importantly, among future and present mental healthcare professionals. Effectively devising and implementing a policy aimed at ending mass incarceration and persecution of those diagnosed with SMI requires individuals of the aforementioned groups to reflect upon their subconscious, foundational biases against those with SMI.