Naming Ourselves: Reflections on Representing and Being Represented

Introduction

There Is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art examines Black women’s representation in American art over the past three centuries.[1] The exhibition aims to answer a relatively simple question: where can one find Black women in art? This question may seem novel to some, but people of color have asked similar questions as they reckoned with their continued absence on gallery walls. In an attempt to answer this question, the exhibition examines visual art from the nineteenth century to today to share the nuanced histories and lived experiences of Black women. Additionally, the exhibition incorporates artwork by Black women to highlight their approaches to art making and their responses to the issue of portraying their race and gender. By centering Black women’s experiences and art, There Is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art integrates marginalized histories into mainstream art historical discourse and public understanding, reflecting a shift that calls for more inclusive narratives in exhibitions and scholarship. This essay will examine three particular concerns that underscore the exhibition’s themes: the problems of representing, being represented, and the burden of representation.

In the history of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA), there have been few exhibitions that focused specifically on representations of Black or African American people, African American art, or the African diaspora. Of note is the museum’s 1964 exhibition, The Portrayal of the Negro in American Painting. This exhibition, groundbreaking at the time, introduced audiences to “positive” depictions of African Americans during the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the fight for racial equality. Representations of women, however, made up a small percentage of the works on view.[2] Since this 1964 exhibition, there have been a small number of exhibitions at the BCMA that have delved into the representation of African Americans, especially in the recent past.[3] Despite this step forward, less than one percent of the permanent collection includes works by Black women artists or features representations of Black women, as recorded at the time of this booklet’s publication. This gap in representation is not an issue that is unique to the BCMA. Most mainstream museums do not have large holdings that examine the portrayal of Black women, or Black people generally, in visual art.

While Black women are largely absent in museum collections, within the last two decades, there has been more of an effort to explore Black women’s representation and womanhood in the art historical sphere. One noteworthy exhibition is Dr. Denise Murrell’s Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (2018), first exhibited at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery.[4] Bringing Black women out from the margins of modern art, this exhibition centered on the models’ lives, networks, and roles in the development of European and American art. Thelma Golden’s groundbreaking exhibition, Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary Art (1994) offered another example for how to examine the nuances of gendered representation.

These two exhibitions and their curatorial approach served as models for the interpretations present in There Is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art. The exhibition positions Black women as the central subject and traces how art has documented their existence and lived experiences. It also places Black women artists in conversation with one another – a first for the BCMA – to showcase their diverse artistic practices. There Is a Woman in Every Color brings these overlooked perspectives to the fore, demonstrating the importance of Black women’s representation and participation in the visual arts while integrating them into our understanding of the history of art.

(In)Visibility in Scholarship

In seeking to answer the question posed at the beginning of this essay – where can one find Black women in art? – there was unsurprisingly a dearth in art historical scholarship that surveyed Black women’s representation and histories. Furthermore, there is no single compendium that examines the image of the Black woman in art. One can find select examples inside illustrated volumes such as The Image of the Black in Western Art, but most of the entries overwhelmingly depict male subjects.[5] One wonders whether this gap in scholarship and women’s limited inclusion in these surveys is due to difficulties in finding examples in public institutions. Artworks that depict Black women are often buried under incomplete cataloging information, or a lack of keywords and finding aids that would make these works more discoverable. But their absence from scholarship is not attributable to this factor alone; the representation of Black women in art has been a subject often ignored, with the women seen as peripheral figures to the “central” subject of a work of art.

How might one attempt to rescue these women from the margins and analyze these works when existing scholarship leaves much to be desired? Given the subconscious and intentional exclusion of Black women from art historical discourse, it is necessary to adopt an interdisciplinary lens when considering the representation of non-Euro American subjects. Texts in the fields of Africana Studies, Cinema Studies, English, Gender and Women’s Studies, and History offered relevant theories, research, and analyses that proved beneficial in researching for this exhibition. Scholars in these disciplines examined representation through the lenses of visual culture, literature, and film, which resonated with conventions of depicting Black women in visual art. Of crucial significance were Black female critics and scholars who wrote about the arts as they pertained to fashioning identity and Black female subjectivity.[6] This essay represents a critical intervention in the art historical discipline and offers scholarship on the subject of Black women’s representation, building on the foundation provided by recent publications and exhibitions.

If we are unaware of Black women in nineteenth-century America, it is not because they were not here…It is because their lives and their work have been profoundly ignored. – Jean Fagan Yellin, 1982

Patterns of Visibility

The experiences of Black women in the United States have been at times recorded and also intentionally excluded. Historian Jean Fagan Yellin wrote: “If we are unaware of Black women in nineteenth-century America, it is not because they were not here; if we know nothing of their literature and culture, it is not because they left no records. It is because their lives and their work have been profoundly ignored. Both as producers of culture and as the subjects of the cultural productions of others, however, their traces are everywhere.”[7] Yellin’s astute comment is a reminder that one must intentionally search for Black women’s history in the visual and historical record.

These records appear in numerous forms such as slaveowner’s diaries and probate records; enslaved women’s memoirs and extant material culture; and paintings and photography. Still, for every extant record that reveals an aspect of Black women’s lives, many accounts are yet to be discovered, and many more will never be known. For the materials that do exist, one must scrutinize them for implicit biases of the period. These prejudices and stereotypes were prevalent in visual culture, literature, and art in the Americas in the eighteenth century and circulated widely throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. The legacies of these representational conventions have imprinted themselves on American society and continue to inform our perception of Black women.

Euro-Americans – Americans of white European descent – often confined Black women to three primary tropes: Jezebel, Mammy, and the Tragic Mulatto. The Jezebel was often depicted as a “middle-aged or young woman governed by her libido” who gained agency through seducing white men.[8] Euro-Americans used this stereotype to depict Black women as immoral and justify acts of interracial sexual assault. While the Jezebel often appeared in printed materials and literature, the Mammy and Tragic Mulatto stereotypes, discussed below, appeared most often in visual art.[9] By the nineteenth century, these tropes were deeply ingrained in the American imagination and embedded in American visual art and popular culture. Many Euro-American artists played a role in disseminating and perpetuating depictions of Mammy and the Tragic Mulatto.

The term “mammy” existed as early as the sixteenth century as a colloquial word for “mother” but gained currency in the early nineteenth-century as southern Euro-Americans began using the word to describe enslaved Black women who cared for their white children and household.[10] In art and visual culture, Mammy was often figured as dark-skinned, obese, and elderly and took on masculinized features that emphasized her ability to endure hard labor while also taking care of the southern plantation.[11] Most times she wore a jolly expression, which distracted and convinced viewers that all was well in the slave-owning South and that she welcomed her subservient status. Enslavers employed this characterization of Mammy as a “happy slave” to combat the condemnation they received from abolitionists advocating for the eradication of slavery. This characterization permeated the material and visual culture of the period and had a lasting presence, with a legacy that endures to this day. The Mammy archetype was found in films such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone with the Wind (1939) and appeared in various household figurines and decorative items.[12]

One artist engaged in this convention of representation was American painter Eastman Johnson (1824-1906). Art historians often describe Johnson’s portrayals of African Americans as “sympathetic,” offering sensitive and humanistic views of African Americans that countered the belief then expressed in the Constitution that they amounted to three-fifths of a human being.[13] However, while evidence of the artist’s sympathy to the plight of Black Americans is visible in his canvases, his views of African Americans were nevertheless embroiled in the negative representations circulating in the period. While the implicit bias operating in Johnson’s paintings may not have been evident to the painter, his 1867 painting Dinah (Portrait of a Negress) (fig. 1) provides an opportunity to analyze more critically his representations of African Americans. The lone figure in the painting fits the typecast of Mammy based on her dark complexion and stocky build. She appears to be in a fleeting moment of rest, perhaps taking a break from grueling labor. Gone is the jovial expression often expected from the Mammy; her somewhat dejected expression leaves the viewer wondering if she is contemplating her status in the United States. Despite the title, it is unclear whether Johnson painted this subject from life or whether this work is a genre scene projecting a persona from his imagination. Unlike many of Johnson’s depictions of African Americans, he forgoes background details entirely, giving the viewer no context as to the narrative behind this “portrait.”

Johnson incorporated African Americans into his paintings between 1861 and 1873. It is unclear the initial motivation that prompted Johnson to take up this subject matter, though art historian Patricia Hills suggests that he was swept up in the surrounding discourse of anti-slavery and racial equality.[14] Like most of his contemporaries, Johnson all but abandoned the subject after the Civil War, and Dinah was one of his last works that pictured African Americans. Interestingly, the painting was never sold or publicly exhibited, and it remained in Johnson’s studio for the remainder of his career.[15]

It is tempting to conclude that Johnson’s portrait of “Dinah” advocated for her humanity as he chose to represent her in oil, the most esteemed medium of the period. However, there is more to consider beyond this surface-level interpretation. Although Johnson, unlike most of his contemporaries, depicted African Americans in his work he still relied on conventional modes of representation. He often employed familiar tropes, such as the Mammy in Dinah, to portray his African American subjects. Perhaps “Dinah’s” forlorn expression reflected Johnson’s consideration of the Mammy in the post-Civil War era: out of place and uncertain of her status. Was his depiction a genuine attempt to draw attention to the difficult circumstances she faced in the United States, or was he simply documenting the highly contentious discourse around slavery? Dinah may not feature overtly racist visual tropes circulating contemporaneously, but Johnson’s work was not unaffected by the negative stereotypes of Black women circulating in the period. His use of the Mammy archetype, even if to invoke the humanity of his subjects, still perpetuated harmful views of Black women and African Americans generally.

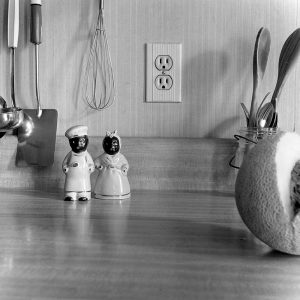

Images of Mammy persisted well into the twentieth century. Capitalizing on this history, conceptual artist Carrie Mae Weems H ’12 (born 1953) incorporated the Mammy into her series American Icons, 1988-9, where this figure often appears with her male counterpart Sambo in mundane domestic scenes. In contrast to Eastman Johnson’s perpetuation of the Mammy archetype, Weems intentionally incorporated figurines of Mammy to challenge historical associations and representations of Black women. In Untitled (Salt and Pepper Shakers), for example, we see the Mammy and Sambo figurines placed on a kitchen countertop with a cantaloupe nearby (fig. 2).

The photograph calls into question the relationship between Blackness, labor, and domesticity, all without the presence of a human subject. Decorative and functional objects depicting the Mammy, such as in Untitled (Salt and Pepper Shakers), continue to be all too common, even, until recently, on the shelves of grocery stores. While a cursory glance at the photograph may suggest that these figurines are harmless, their presence demonstrates that the legacy of slavery and racism in fact pervades every facet of American life—a harmful influence made all the more powerful by its very invisibility. By placing the Mammy figurine in the kitchen, Weems brings to mind the Black women’s labor during the antebellum period. Weems reminds us of the legacy of Black women’s labor in service to their enslaver. Her critique and intervention problematize the ongoing appearance of the Mammy, and other derogatory archetypes, in mainstream society and commercial products such as Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix.

![DESIDERIO LAGRANGE (French-Mexican, 1849-1926), [Wet Nurse of African Descent and White Infant], mid-to-late 19th century, cabinet card, 4 1/4 x 6 1/2 in. (10.8 x 16.51 cm), Museum Purchase, Gridley W. Tarbell II Fund, 2020.22.1. Artwork in the public domain.](https://courses.bowdoin.edu/there-is-a-woman-in-every-color-2021/wp-content/uploads/sites/502/2021/05/LaGrange_Booklet-192x300.jpg)

The pose of the individuals in the photograph suggests an intimacy and familiarity between the infant and the woman. However, this intimacy was cultivated through the exploitation of the woman’s body. Throughout North America, it was a popular convention to include the wet nurse in photographs of wealthy Euro-American children. On a practical level, this may have reflected care required by the children during the studio session. Yet, even if the warmth of familial bonds were to be cited as an explanation for the presence of Black women in such photographs, these relationships reflected a form of coercion and their poses signal her subservient status in society. Relegated – quite literally – to supporting roles, the appearance, even in a nurturing role, of the women in such images served as a visual record of the slaveowner’s wealth, status, and property.

The Tragic Mulatto was the offspring of illegal miscegenation; she was considered Black due to the “one-drop rule,” which asserted that anyone with even one-eight African ancestry was considered Black. She was forever at odds with her identity, existing on the outskirts of her Blackness and whiteness. The term “mulatto” was originally developed by Spanish and Portuguese colonizers to describe people of “mixed breed,” the literal translation being “young mule,” which included those of mixed European and African descent. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the term spread throughout the British and French colonies, used to describe any persons of mixed race.

Images of “mulatto” women are also found throughout American art and visual culture. Often depicted as fair skinned, these individuals of mixed race are typically identified with African origins through dress.[18] These artworks’ main priority was to emphasize her exotic qualities while acknowledging her Blackness through stereotypical accoutrements. Such is the case in French artist Deschamps de la Talaire’s (active 1760) Portrait of a Biracial Woman, 18th century (fig. 4).

Working in the tradition of portrait de fantaisie, an artistic genre that features imagined sitters, Deschamps tells us more about his own views of multiracial women than about a real individual.[19] The fictitious woman’s mixed heritage is emphasized through her costume, particularly the headwrap, which was often worn by Black women across the African diaspora. Although the impetus behind this pastel is unknown today, Deschamps may well have encountered women of African descent through his travels in the Caribbean or France. Perhaps he drew inspiration from visual representations of “mulatto” women that circulated in visual and print culture.

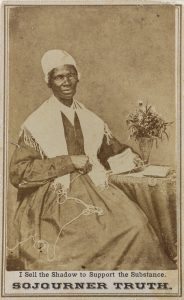

If Black women were all too often subjected to stereotypical representations, some women pushed back. Sojourner Truth’s carte de visite exemplifies her efforts toward self-representation and personhood, a feat achieved by few African Americans in the antebellum period (fig. 5). Unlike the cabinet card of the wet-nurse, Sojourner Truth holds a steady gaze with the viewer, daring the viewer to challenge her confidence. The carte de visite features her well known statement: “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” informing the viewer that Truth – and her alone – can have authority over her likeness. By copyrighting her cartes de visite, she supported her abolitionist and suffragist efforts. Sojourner Truth and other Black women used portrait photography to portray their dignity, individuality, and combat negative images circulating in the dominant visual culture of the period.[20] In this way, Truth’s assertion of agency over her own representation bears comparison with that seen of African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who is considered the most photographed man of the nineteenth century.[21]

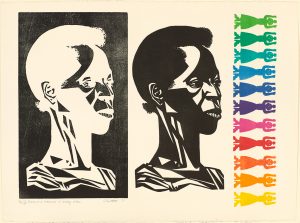

In recent years, artists have continued to grapple with the issue of representation. One artist who often wrestled with these challenges was Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012). In There is a Woman in Every Color (fig. 6), a print created in 1975, Catlett experimented with several techniques to figure the Black woman. She intentionally renders the same Black woman’s face twice using tonal opposites. Catlett prioritizes the individual Black subject featured in the positive/negative images, and her presence overwhelms the composition. This positive and negative dichotomy plays on the never-ending contrast between black and white in America’s racialized society. The duality of the prints may suggest the desire for racial equality. Catlett couples these two figures with a band of multicolored Black women on the right, their race signaled through their hairstyle and not the colors of the ink. Instead, their colorful array evokes multiple identities. Observing these components together, Catlett’s work can be read as a metaphor for the artist’s commitments to global civil rights, equality, and feminism across racial and ethnic lines – an early expression of intersectionality. At the same time, her repeated use of Black women as the subjects of the work suggests that for Catlett, Black identity and experience are central to the framework of inclusion and equity. This act of centering Black women echoes the spirit of this exhibition.

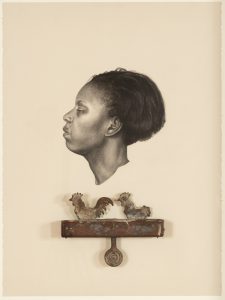

For Whitfield Lovell (born 1959), the challenge to represent Black women fully asserts itself in his work, Kin XLVI (Follie), 2011 (fig. 7). We encounter the profile of a woman’s face rendered above a shooting gallery target featuring two roosters. Kin XLVI provides a glimpse into Lovell’s practice as an artist, namely, his focus on questions related to African American invisibility and representation in the historic record. Lovell often works from portraits of African Americans produced within the period between the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil Rights Movement. He scours photographic material and ephemera ranging from studio portraits, IDs, and mugshots, quite literally revealing African Americans’ presence in plain sight.

In Kin, as with most of Lovell’s works, he gives the viewer limited information about the subject, making it difficult to situate her in the historical record. Based on her straightened hairstyle – either chemically relaxed or pressed by hot comb – the woman depicted likely lived in the early- to mid-twentieth century. While her portrait suggests her dignity and stoicism, the presence of the shooting gallery target evokes the past and present violence experienced by Black women in the United States. Lovell’s assemblage delivers a multifaceted view into the lives and experiences of Black women, holding space for both their grace and dignity while acknowledging their hardships. Lovell’s work is an inspired take on representing Black women in art, and his nuanced view of their experience is likely informed by his understanding of the visual legacy of their representation and his own life as an African American male.

Black Bodies: Past and Present

While several conventions of representation existed in the nineteenth and twentieth century, one subject was mostly absent from art: the Black female nude. The (mostly white) female nude has appeared in art across culture and time, as early as antiquity. While the subject has been tackled by many artists, as art historian Lisa E. Farrington observes, there exists a “paucity of images of the black female nude in the history of Western ‘high’ art.”[22] Indeed, Black women’s nude presence is exceedingly rare in American fine art before the twentieth century. This is underscored by the absence of early nude depictions in the exhibition. Black artists largely avoided depicting the Black female nude, which arguably did not appear in African American art until the beginning of the 1960s.[23] When they did, the subject was often taken up by male artists.

When the Black female nude does appear, it is found less in works of art than in anthropological and ethnographic photography of the nineteenth century. Such images often resulted from the subject’s coerced subjugation to the “objective” study and documentation of their race and physiognomy. Some well-known examples of these photographs include those taken by Joseph T. Zealy at the behest of Harvard zoologist Louis Agassiz in 1850.[24] Reflecting the racism that shaped science, the depiction of Black women’s bodies instead reinforced the stereotypical views of Black women associated with the Jezebel figure. Black women’s bodies were, as art historian Lisa Gail Collins suggests, “too entangled in [their] charged flesh” to reflect their humanity or take on new meanings in society, a direct contrast to the Black male body’s prevalent use for abolitionist messaging and notions of freedom.[25] Society deemed Black women’s bodies hypersexual, exotic, and libidinous.

The legacy of the sexually charged Black body existed well into the twentieth century, and it forces one to question the intent behind the images by William Witt (born 1921) in the 1940s (fig. 8). Here, the woman’s gaze is not directed at the viewer or the camera, but her body is on full display. There has been no attempt to conceal her body for modesty’s sake by the staging of the photograph or the positioning of the camera. Witt’s oeuvre was influenced greatly by the documentary photography produced during the Great Depression under the Farm Security Administration, and he is mostly known for his scenes of New York City life. However, Witt seems to have had a brief fascination with the nude figure between the 1940s and ‘60s.

Of the examples of Witt’s photographs in the BCMA’s collection, most of the nude photographs feature white women. A clear distinction in Witt’s images of white and Black nude bodies is that his images of white women feature the names of the sitters, whereas those taken of Black women identify them by race alone. The absence of the Black sitters’ names may have been an unconscious decision on the part of Witt. However, given his penchant for documentary photography, perhaps his focus was to record the Black body abstractly, void of any individuality or personal recognition. One wonders what power dynamics are at play between the white photographer and the Black subject and how these photographs were meant to function. Did he see these women as deserving of their humanity when he made the image, or were they to function as pseudo-scientific documentation? There has been no attempt to individualize the subject, as the title suggests that this is simply a “Black Nude” figure.

To name ourselves rather than be named we must first see ourselves. For some of us this will not be easy. So long unmirrored in our true selves, we may have forgotten how we look…And we – I speak only for black women here – have barely begun to articulate our life experience. – Lorraine O’Grady, 1994

Contemporary women artists have incorporated the Black woman, and her nude body, into their work to reclaim agency over their bodies and insert new modes of representation into the art historical canon. Deana Lawson’s (born 1979) Sharon, 2007, which has a similar composition to Witt’s photograph, is one such example. However, Lawson’s photograph deviates from the unnamed, documentary style of Witt’s photograph and presents an intimate portrayal of a woman named Sharon. Much like Lawson’s entire oeuvre, Sharon captures a vision of Black women that Lawson could access due to her identity. Her ability to relate to her subjects from a level of shared community allows her to use her portraits to document and insert new views of Black people and their culture into American art.

Lawson’s works counter the distorted images and connotations ever-present in the dominant culture.[26] However, Lawson’s oeuvre does not exist in a vacuum. As artist and critic Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934) reminds us in her 1994 essay “Olympia’s Maid: Black Female Subjectivity,” quoted above.[27] Black women have been exploring their subjectivity in a variety of art forms for decades, as a way to reckon with the absence of their physical presence but also their experiences and voices. This searching for themselves is present in the works by novelists Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) and Toni Morrison (1931-2019) to artists such as Alison Saar (born 1956) and Mickalene Thomas (born 1971).[28] In exploring what it means to be a Black woman and depict their experiences, these writers and artists have started to articulate the intricacies of Black women’s lives. It is this personal reflection on Black women’s experiences, as presented by a Black woman, that makes Lawson’s work function differently from William Witt’s photograph.

In analyzing several conventions used to portray Black women, it becomes clear that visual art produced in the Americas during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries often perpetuated limited and biased views of Black women. However, Black artists also figured Black women into their work, often times countering mainstream images.

This role [as a representative] has fallen on the shoulders of black artists not so much out of an individual choice but as a consequence of structures that have historically marginalised their access to the means of cultural production. – Kobena Mercer, 1990

The Burden of Representation

While artists struggled to capture the multifaceted nature of the Black woman, Black women entering the art world in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were met with a unique challenge: the expectation that they “correctly” represent their race in their art. As art historian Kobena Mercer suggests, this expectation results from the demand for more representation of people of color in art as well as structural inequalities that have placed Black women artists and other artists of color on the margins.[29] Working against both racial and gender injustice and experiencing exclusion and marginalization, they also had to fight against the assumption that their work should address the longstanding history (including its absences) of Black women’s representation in art. Was it their responsibility to produce art that countered these historical images, or could they explore other facets of their creativity? How did they navigate their experiences, artistic production, and identity?

The burden of representation has been a constant issue and debate within the discourse on African American art. Questions around the function of art and its place in Black liberation has often prompted rebuttals advocating for Black creativity and freedom of expression. The women artists featured in There Is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art have responded in various ways to this perpetual expectation of simultaneously representing their race and gender and countering racial and gendered stereotypes. And yet, not all Black women artists think alike or respond similarly. While this may seem to be an obvious statement, it is important to reiterate given assumptions in mainstream society that people within a marginalized group operate as a monolith. The artists included in the exhibition span several centuries and generations and have different lived experiences that inform their artistic responses.

Black women artists have long battled the tendency of audiences to want to read the artist’s identity in their work. Art historian Charmaine Nelson, for example, investigates sculptor Edmonia Lewis’s (1844-1907) penchant for figuring her sculptures with European physiognomy, even when depicting subjects of Native American or African American origin. In Lewis’s sculpture Minnehaha (1868), the subject’s clothing is the primary indicator of her indigenous identity (fig. 9); her facial features are not sculpted in ways that overtly reference her own ethnicity. Perhaps by depicting Native American and African American peoples with European facial features, Edmonia Lewis attempted to suppress her own identity as an African American and Anishinaabe/Ojibwe woman, distancing it from her works and her practice as an artist. As Edmonia Lewis was navigating predominately male Euro-American artist circles, her choice to render all her subjects with European features might have been a way to place her work on equal footing to her white male contemporaries.

In the early twentieth century, many African American women artists such as Augusta Savage (1892-1962) dedicated themselves to countering stereotypical representations of African Americans that circulated in print and visual culture. Some of this work aligned with Alain Locke’s insistence that “black artists had to do more with the black experience and, especially, with their heritage.”[30] This corrective agenda was fueled by respectability politics of the period and was often done in collaboration with community reform movements. Savage, one of the leading figures in the Harlem Renaissance, focused her career on producing noble views of African Americans. Her sculpture Gamin is one such example (fig. 10). Savage took great care to sculpt this bust of a young child, dressed in a wrinkled shirt and flat cap. The painted sculpture embodies the spirit of Augusta Savage’s works in that it represents the dignity of African Americans that many Black artists sought to promote during the Harlem Renaissance.

Around the mid-twentieth century, some artists turned their practice into a form of activism. Elizabeth Catlett often explored themes of race, identity, and the African American experience in her work. She was inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and socio-political events in Mexico. An African American artist, she moved to Mexico in the 1940 and pursued dual citizenship. In her article, “The Role of the Black Artist,” she made clear her opinions on the role of Black art: “The how-to and whereby of reaching the mass of black people through their art. This is the principal preoccupation of all artists who consider themselves first black and then artists. I cannot speak for the others who are artists first and black when it is convenient to be so.”[31] Catlett found it crucial that black artists participate in the movement for Black liberation and that their art reflect their social engagement. Catlett held firm to her activism and was ultimately barred from returning to the United States until 1971 due to her participation in leftist organizations in Mexico. She created socially engaged work that “transcended the geographic distance” and resonated with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.[32]

Not all artists shared Savage and Catlett’s belief that their art should reflect social or political matters of the moment. Artists such as Alma Thomas (1891-1978) delved deeply into abstraction as a way to distance herself from the expectation that Black artists’ work should deal directly with social justice and critique (fig. 11). Abstraction provided a level of freedom and unburdened creativity, allowing one to forge their own path and expand the possibilities afforded to Black artists. Thomas once stated: “I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People struggling, having difficulty. You meet that when you go out, and then you have to come back and see the same thing hanging on the wall. No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at.”[33] The “ugly things,” as Thomas put it, might be described as the suffering and hardships faced in the African American community. And when asked whether she considered herself a Black artist, she answered: “No, I do not. I am a painter. I am an American.”[34]

This refusal of categorization echoes similar sentiments held by assemblage artist Betye Saar (born 1926). Saar’s work often moves beyond depicting Blackness in a monolithic form and draws inspiration from history and multiple religions. In 1990, she chose to distance herself from exhibitions that emphasized her race or gender, stating: “Midway through 1989 I made a decision not to be separatist by race or gender. I decided not to become involved with shows that had ‘woman’ or ‘black’ in the title. What do I hope the nineties will bring? Wholistic [sic] integration – not that race and gender won’t matter anymore, but that a spiritual equality will emerge that will erase issues of race and gender.”[35]

Unfortunately, the “spiritual equality” that Saar hoped for has yet to be realized. American society has yet to move past race and gender inequality and giving women of color a platform to express themselves is still necessary. Although Saar did not want her work to be contextualized on the basis of her race or gender, her inclusion in this exhibition is intentional. By including her work and outlook in the exhibition, we gain multiple, and differing, perspectives on what it means to be an artist who is both Black and woman. Differing opinions on the function and role of art are also demonstrated in Betye Saar’s denouncement of Kara Walker’s silhouette work and their display of stereotypical features and graphic events.[36]

In today’s art world, artists such as Mickalene Thomas, Deana Lawson, and Amy Sherald (born 1973) often center Black women and their experiences in their artistic practices. This centering reflects a commitment to privileging individuality in representations of Black women, casting aside the monolithic view of the Black community. They simultaneously counter negative associations present in the visual sphere while showing nuanced experiences of Black women and expressions of their Blackness.

In Mickalene Thomas’s Tell Me What You’re Thinking, the artist references the paintings of European male artists who frequently placed women in suggestive, even submissive, postures (fig. 12). In this photograph, however, the model reclining in an odalisque pose exudes confidence and commands attention. Thomas’s work is black female subjectivity on full display, allowing the viewer to engage meaningfully with the changing representations of Black women in art.

Some contemporary artists gravitate towards conceptual and abstract art for the freedom it allows for investigating multiple avenues. Artists such as Leslie Hewitt (born 1977) and Julie Mehretu (born 1970) find inspiration in sites of memory, history, and personhood. Hewitt brings her conceptual approach to still lives, investigating, as she puts it, “the fragile nature of quotidian life.”[37] In Riffs on Real Time (8 of 10), Hewitt combined print ephemera, personal iconography, and textual surfaces to reflect the passage of time, memory, and experience (fig. 13). While she often sources archival material from African American communities, the themes she explores are universal.

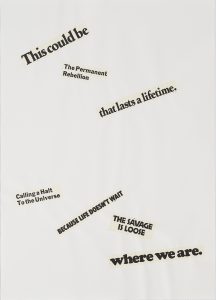

Other artists such as Nyeema Morgan (born 1977) and Lorraine O’Grady seek inspiration from literary sources, providing them an opportunity to experiment with, engage, and challenge the histories of print culture and literature in American society. In O’Grady’s Cutting Out the New York Times, she scanned the Sunday New York Times over a 26-week period in search of words from which she would develop poems that reflected the political and social moment. In 2017, O’Grady returned to the 1977 series, making new meaning of the phrases she cut out forty years before. In the series’ statement piece (fig. 14), the beginning of the poem – “This could be/ The Permanent Rebellion/ that lasts a lifetime” – encapsulates the spirit of O’Grady’s series and its haiku-like poems. Her 2017 series express personal thoughts and ideas in response to social issues and societal changes through the vehicle of public language.

Today’s Black women artists produce art that, taken collectively, acts to dismantle expectations placed on them even if their approaches vary greatly. Past and recent calls for inclusivity in exhibitions and collections are finally being acknowledge by white audiences and mainstream cultural institutions.[38] As museums scramble to address the gaps in their collections, the demand for works by Black women artists has increased, and as a result, the value of these works has risen. At the same time, however, contemporary Black women artists are still being judged for whether they choose to represent Black experiences or tackle other subjects. Julie Mehretu summarizes it best: “Black artists are too often expected to explain who they are in their work, which is based on racist ideas of authenticity.”[39] The same expectations are not placed on white male artists to represent their race or, to the same extent, on white women artists to represent their entire gender. Black women artists will continue to produce art that challenges the demands and expectations placed on them, at least for the foreseeable future. It is the responsibility of art historians, curators, gallerists, and cultural workers to give these artists the platform to share their vast and varied perspectives, stand in their subjectivity, and allow them the freedom to create and produce art as they please. The exhibition creates space for their differing approaches to art making, placing equal value and emphasis on the artists’ practices.

Conclusion

The representation of Black women in art has evolved since the nineteenth century to today. Narrow, and often negative, views of Black women appeared in print and visual culture, and their legacies are still present in American culture today. While these stereotypes have persisted, Black women have had a parallel history of countering these views through their self-fashioning in photography and producing art that combated negative perspectives on their lives and experiences. Black women artists have also explored their artistic prowess, gravitating toward a variety of subjects that allowed them to express their creative freedom even against pressures to speak for their entire race or for Black women everywhere.

While much progress has been made, there is always more work and learning to be done. Some artists of the twentieth century are just now experiencing widespread recognition late in their career, as demonstrated by recent and upcoming retrospectives. Emerging artists are standing in their creative freedom and demanding more from the art world in terms of equal representation in museums, galleries, and the art market. They also understand the role and impact of their art. In speaking about her work, artist Amy Sherald (born 1973) stated: “The more museum spaces that I can fill up, the more change these paintings can project. They can be employed in many different ways but hanging them on walls in accessible public spaces is essential. If you know African-American history, then you recognize the power of their presence.”[40] With the “power of presence” in mind, it is my hope that this exhibition, with its attention to historical representations and its insertion of their artistic voices, will make space for Black women in art and advocate for their permanent inclusion moving forward.

Endnotes

[1] The term “Black” is used here to encapsulate the breadth of identities tied to the African diaspora, as seen throughout the exhibition. Where possible, terms to further specify race and ethnicity are used, such as “African American.”

[2] For more on these exhibitions, see Guy C. McElroy, Facing History: The Black Image in American Art, 1710-1940 (San Francisco, Bedford Arts; Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1990); Bowdoin College Museum of Art, The Portrayal of the Negro in American Painting (Brunswick: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 1964).

[3] For recent exhibitions see Fifty Years Later: The Portrayal of the Negro in American Painting – A Digital Exhibition (2014), This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Representation in American Art, 1913 to the Present (2016), Second Sight: The Paradox of Vision in Contemporary Art (2018), and African/American: Two Centuries of Portraits (2019).

[4] Relevant exhibitions also include Black Womanhood: Images, Icons, and Ideologies of the African Body (2008-9, curated by Barbara Thompson, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College) and Beyond Mammy, Jezebel, & Sapphire: Reclaiming Images of Black Women (2016-17, curated by Jessica Hunter-Larsen and Megan Valentine, IDEA Space, Colorado College).

[5] Several surveys examine the representation of Black people in Western and American art. See Benjamin Griffith Brawley, The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States (New York: Duffield and Company, 1921); Alain Locke, ed., Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art (Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1940); Ellwood Parry, The Image of the Indian and the Black Man in American Art, 1590-1900 (New York: G. Braziller, 1974); David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, The Image of the Black in Western Art, vols. III, IV, and V (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010-2014).

[6] Some relevant authors are Coco Fusco, bell hooks, Kellie Jones, Michele Wallace, and Judith Wilson.

[7] Jean Fagan Yellin, “Afro-American Women, 1800-1910: Excerpts from a Working Bibliography,” in All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave, 1st ed. (New York: The Feminist Press, 1982), 221.

[8] Mahassen Mgadmi, “Black Women’s Identity: Stereotypes, Respectability, and Passionlessness (1890-1930),” Revue LISA/LISA E-Journal 7:1 (2009), para. 5, https://doi.org/10.4000/lisa.806.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “mammy, n. (and int.),” Oxford English Dictionary Online, March 2021, Oxford University Press, https://www-oed-com.ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/view/Entry/113188?redirectedFrom=mammy (accessed March 1, 2021).

[11] Maythee Rojas, “Embodied Representations,” in Women of Color and Feminism (Berkeley: Seal Press, 2009), 35; Patricia Morton, “Myths of Black Womanhood,” in Disfigured Images: The Historical Assault on Afro-American Women (New York: Praeger, 1991), 7.

[12] The California African American Museum recently installed the exhibition, Making Mammy: A Caricature of Black Womanhood, 1840-1940, curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, Taylor Bythewood-Porter, and Brenda Stevenson. The exhibition was on view from September 2019 – March 2020.

[13] Patricia Hills, “Painting Race: Eastman Johnson’s Pictures of Slaves, Ex-Slaves, and Freedmen,” in Eastman Johnson: Picturing America, by Teresa A. Carbone and Patricia Hills (New York : Brooklyn Museum of Art, in association with Rizzoli International Publications, 1999), page numbers?

[14] Ibid, 121.

[15] Ibid, 157.

[16] Historian Sally G. McMillan suggests that one-fifth of white women in the South relied on enslaved women to breastfeed their children. E. West and R.J. Knight, “Mothers’ Milk: Slavery, Wet-nursing, and Black and White Women in the Antebellum South,” Journal of Southern History 83:1 (February 2017), p. 42, https://doi.org/10.1353/soh.2017.0001.

[17] Juan Javier Pescador, “Inmigración femenina, empleo y familia en una parroquia de la ciudad de México: Santa Catarina, 1775-1790,” Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos 5:3 (September-December 1990), 744, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40315397. For information on Mexico’s wet-nursing practice, see Juan Javier Pescador, “Vanishing Woman: Female Migration and Ethnic Identity in Late-Colonial Mexico City,” Ethnohistory 42:4 (Autumn 1995), p. 617-626, https://www.jstor.org/stable/483147.

[18] The Tragic Mulatto stereotype mostly appears in literature such as Lydia Maria Child’s The Quadroons (1842) and Slavery’s Pleasant Homes (1843), and in films such as the highly controversial The Birth of a Nation (1915).

[19] This interpretation derives from the label inscription found on the back stretcher. Based on the condition of the label and its wear, it is likely that this was added around the time of the pastel’s creation.

[20] For additional examples of self-fashioning, see Unidentified Artist, Untitled (half-length portrait of African American woman, seated and leaning against tapestry-covered table), 1840s-1850s, hand colored sixth-plate daguerreotype, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, 2008.305; Unknown Artist, Portrait of a Biracial Woman, c. 1855-60, quarter plate ambrotype in thermoplastic case, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME, 2020.22.4.

[21] Celeste-Marie Bernier, “A Visual Call to Arms against the “Caracature [sic] of My Own Face:” From Fugitive Slave to Fugitive Image in Frederick Douglass’s Theory of Portraiture,” Journal of American Studies 49: 2 (2015): 323-57, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24485634.

[22] Lisa E. Farrington, “Reinventing Herself: The Black Female Nude,” Woman’s Art Journal 24:2 (Autumn 2003 – Winter 2004), 15, http://www.jstor.com/stable/1358782.

[23] Judith Wilson, “Getting Down to Get Over: Romare Bearden’s Use of Pornography and the Problem of the Black Female Body in Afro‐U.S. Art,” in Black Popular Culture, eds. Gina Dent and Michelle Wallace (Seattle: Bay Press, 1992), 112–22; Jessica Dallow, “Reclaiming Histories: Betye Saar and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood,” Feminist Studies 30:1 (Spring 2004), 76, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3178559.

[24] For more on this collection, see Ilisa Barbash, Molly Rogers, and Deborah Willis, eds., To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (Cambridge: Peabody Museum Press; New York: Aperture, 2020) and Carrie Mae Weems’s work From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995-6, Chromogenic color prints with sand-blasted text on glass, 28 works: 26 ¾ x 22 in.; 4 works: 22 x 26 ¾ in.; 2 works: 43 ½ x 33 ½ in., Museum of Modern Art, New York.

[25] Lisa Gail Collins, “Economies of the Flesh: Representing the Black Female Body in Art,” in The Art of History: African American Women Artists Engage the Past (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 40-41.

[26] Janell Hobson, “The ‘Batty’ Politic: Towards an Aesthetic of the Black Female Body,” Hypatia 48:4 (Autumn-Winter 2003), 89, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3810976

[27] Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” in New Feminist Criticism: Art/Identity/Action, Joanna Frueh, Cassandra L. Langer, and Arlene Raven, eds. (New York: Harper Collins, 1994).

[28] Ibid.

[29] Kobena Mercer, “Black Art and the Burden of Representation,” Third Text 4:10 (1990), 65.

[30] Alain Locke (1885-1954) was a formative American writer, educator, and patron of the arts. He became known as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance.” See bell hooks, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: New Press, 1995), 5.

[31] Elizabeth Catlett, “The Role of the Black Artist,” The Black Scholar 6:9 (June 1975), 10-11.

[32] Dalila Scruggs, “Activism in Exile: Elizabeth Catlett’s Mask for Whites,” American Art 32:3 (Fall 2018), 5.

[33] Munro, E., “The Late Springtime Of Alma Thomas,” The Washington Post (1974-Current File), 15 April 1979, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1979/04/15/the-late-spring-time-of-alma-thomas/f205cbf7-3483-4cc4-8a52-7f5eacda7925/

[34] Ibid.

[35] Jessica Dallow, “Reclaiming Histories: Betye Saar and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood,” Feminist Studies 30:1 (Spring 2004), 87, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3178559.

[36] See Arlene R. Keizer, “Gone Astray in the Flesh: Kara Walker, Black Women Writers, and African American Postmemory,” PMLA 123:5 (October 2008) Special Topic: Comparative Racialization, p. 1649-1672. For Saar’s letter writing campaign against Walker, see Hilton Als, “The Shadow Act: Kara Walker’s Vision,” The New Yorker, 8 October 2007, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/10/08/the-shadow-act.

[37] Leslie Hewitt, “Artist’s Statement,” December 2009, Foundation for Contemporary Art, https://www.foundationforcontemporaryarts.org/recipients/leslie-hewitt. Accessed 7 January 2021.

[38] For recent discussions of museums attempting to diversify their collections, see Brian Frye, “The Baltimore Museum Wants to Diversify Its Collection; It Should Be Allowed to,” Hyperallergic, 25 November 2020, https://hyperallergic.com/600604/the-baltimore-museum-wants-to-diversify-its-collection-it-should-be-allowed-to/; Naomi Rea and Eileen Kinsella, “As Museums Desperately Try to Diversify Their Collections, They Now Face Another Problem: How to Pay for It in a Financial Crisis,” Artnet News, 11 February 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/art-museum-diversity-collections-1942997; Emma Jacobs, All Things Considered, ‘Can I Make Sure That I’m Not The Only One?’ Artist Helps Museum Diversify Collection, National Public Radio, podcast audio, 16 September 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/09/16/912930694/how-can-i-make-sure-that-i-m-not-the-only-one-artist-helps-museum-diversify-coll.

[39] Fawz Kabra, “Julie Mehretu on the Right to Abstraction,” Ocula Magazine, 16 December 2020, https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/julie-mehretu/

[40] Tiffany Y. Ates, “How Amy Sherald’s Revelatory Portraits Challenge Expectations,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/new-work-amy-sherald-focuses-ordinary-people-180973494/