By Camille Amezcua ’22

Art has the power to be contagious. The exhibition, There is A Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art opens up a space in which art imbues a conversation with the constructions of gender, sexuality, and identity of women of color to reimagine stereotypical assumptions of personhood. Through the mediation of images, the exhibition actively begs its audience to grasp art as a constant challenging of social performance and as a way to confront a cultural memory rooted in racism and sexism. In my essay, I will examine artist Betye Saar and her piece Now You Cookin’ With Gas featured in the exhibition. Saar is an American artist known for her work in the medium of assemblage. She is a storyteller, crafting visual biographies with found objects to recollect narratives of identity, history, and memory. Now You Cookin’ With Gas is a part of series of six silk-screened collages that correspond to author, anthropologist, and filmmaker Zora Neale Hurston’s short stories. Saar threads together her artistic vision and Hurston’s words to create a visual language that seeks to tell of both feminine and racial realities.

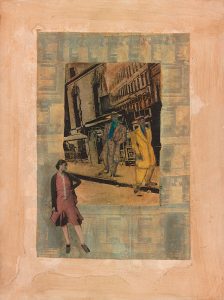

Now You Cookin’ With Gas is the last story in Hurston’s and Saar’s book, Bookmarks in the Pages of Life: A Selection of Short Stories. Hurston’s original, unedited short story appeared as the “Story in Harlem Slang,” which was published in The American Mercury (1942). Saar portrays a woman, her hand propped up on her jived hip and her profile turned in a slight direction toward two men. Hurston begins the story, “Wait till I light up my coal-pot, and I’ll tell you about this Zigaboo called Jelly.”[1] Jelly is a “seal-skin brown and papa-tree-top-tall… skinny in the hips” built man.[2] He dresses in his “zoot suit with the reet pleats” to peruse 132nd Street where he meets up with his colleague Sweet Back.[3] Together they see a girl, stating “this one looked prosperous.”[4] The two men speak loud enough for her to hear down the avenue, and as she halts and braces her hips with her hands–as Saar has illustrated–she says, “A Zigaboo down in Georgey where I come from asked a woman that one time and the judge told him ‘ninety days’”[5] The men continue their degrading talk, claiming she’s good for the money, but the girl simply laughs and snorts, “Nobody ain’t pimping on me. You dig me.” (239). Her laughter heightens, her tone of amusement growing harsher and harsher as the men make a greater mockery of themselves. She retorts back at them, threatening their advances, “touch me and I’ll holler like a pretty white woman!”[6] She is the one who walks away. She leaves the men to squander in their foolish swag. They try to boast again of the women who feed their riches and yet leave to go scrap a dime from running another’s errands, their ears still ringing from the girl’s roar.

Saar curates Hurston’s language to visually depict the prosperous woman to exist on the edge of the imagined Harlem sidewalk. She is physically independent of the men who look upon her. She is self-possessive, unaffected by their glares of desire. The identity of the woman is at the center of the piece. Saar creates a space that grounds itself in familiar aesthetics while also pushing its audience into an imaginative space in which implicit tensions can be further seen and discussed.

Driven by the need to communicate knowledge through the intimacy of experience, it is through Saar’s art that one finds the ability to assert themself beyond bias. She understood how to be a woman, how to be Black, and how to be an artist all separate from one another. Saar then wove these identities together in order to reimagine stereotypes, and to break assumptions–such as the meanings of “women” and “Black.” Now You Cookin’ With Gas exposes the racial and feminine implications of imagery to present a subversive telling. How does the physical placing of the girl, separate from the male gaze –reversing the power dynamic– overturn the subservient role that Black woman usually play in imagery? The work refigures fetishes in order to reclaim imagery that help them be seen differently. Saar commands a sense of power, while also infecting it. Her artwork is a part of a great continuum of Black history in America. In 1998 Saar wrote a poem in which she says, “By shifting the point of view / an inner spirit is released / Free to create.”[7] Her work in Now You Cookin’ With Gas, along with every artwork in There is A Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art, has the ability to transgress social and historical boundaries, for the art will never end in its performance as a social movement.

Bibliography

Hurston, Zora Neale, Henry Louis Gates, Sieglinde Lemke, Alice Walker, and Zora Neale Hurston. “Now You Cookin’ With Gas.” Essay. In The Complete Stories, First ed., 233–41. New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2008.

Saar, Betye. Betye Saar: as Time Goes By. Georgia, GA: Savannah College of Art and Design, 2000.

Endnotes

[1] Hurston, Zora Neale. (2008). “Now You Cookin’ With Gas.” In The Complete Stories, First ed., 233.

[2] Ibid, 234.

[3] Ibid, 234.

[4] Ibid, 237.

[5] Hurston, Zora Neale. (2008). “Now You Cookin’ With Gas.” In The Complete Stories, First ed., 238.

[6] Ibid, 240.

[7] Saar, Betye. (2000). Betye Saar: as Time Goes By. Georgia, GA: Savannah College of Art and Design, 9.