This exhibition is the final product of months of thinking about how society conceptualizes motherhood. When we first looked at the BCMA’s collection of images of women or by women, we realized many of the pieces related to the idea of woman as mother. Spanning most of Western art history, there were dozens of images of pregnant women, women with their children, women with their families, artists as mothers, artists’ renderings of their mothers. Women and their bodies have been metaphorized so thoroughly over the centuries in Western art that we felt that these depictions of motherhood must reflect something of the priorities of the societies that produced them. We began to ask ourselves: what did these changing illustrations of mother tell us about the way Western society has evolved? What societal concerns and priorities of their time did the images illuminate?

This understanding of women as essentially a sign in art is rooted in the linguistic concept of semiotics. Semiotics proposes that images are signs made up of a signifier and a signified. Signs are any unit that conveys value or meaning between people. The signifier is the vessel we use to communicate the sign, and the signified is the idea the sign represents. In the case of art, the image is the signifier and the idea it represents is the signified. These signifiers can be thoughts of as symbols representing a larger idea, the sign.

Scholar Elizabeth Calle puts forth the idea that artistic renderings of women have represented something besides a human woman, writing that it is “possible to see ‘woman’ not as a given, biologically or psychologically, but as a category produced in signifying practices…The form of the sign—the signifier in linguistic terms—may empirically be woman, but the signified is not “woman” (62). As such, women in art often signify something other than themselves–goodness, piety, temptation, modernity–and what we see women as representing seems to reflect something of our societal values and preoccupations. In the same vein, we attempted to figure out what these varied representations of motherhood told us about the societies that produced them, viewing renderings of mother as a sign. Images of mothers can help us to understand the values, preoccupations, and interests of the societies from which they originate.

As such, we looked at images of mother across time, paying attention to the historical context and systems of representative imagery that surrounded them. Our story starts in the Renaissance, when images of the Virgin Mary and child exploded in popularity, spreading an idealized conception of motherhood that linked fertility with piety and salvation. The prominence of religious images of motherhood is challenged by increased secularization and Enlightenment values during the 18th century, but the idealizing of the mother which Mary catalyzed is not. Eschewing renderings of Mary herself, some artists began to depict her and her values in the image of common, contemporary people, and some turn to pre-Christian traditions to build upon idealized motherhood.

The late 18th century and early 19th century brought the Industrial Revolution, ushering in a new modernity and a new understanding of the roles of mothers. Modernity brought technology, jobs, access to goods, but fast production and factories also came grueling working conditions, scheduled workdays, dangerous conditions, child labor, and a glaring absence of labor laws. Such a world was scarier, more dangerous, unpredictable, and one that demanded unsung sacrifices from everyday people, and this began to be depicted in art. Sacrifice has, of course, been a part of Western culture far before the industrial revolution, but previously we saw the lionzing of heroic sacrifices by important and extraordinary people, mostly in history paintings and religious paintings. In this period, sacrifice is depicted as widespread, and the mother, raising vulnerable children in a scarier world, is depicted as a tragic figure, one who must make sacrifices, or as a sacrificed figure.

If industrialization ushers in a more violent world, one where children can endure dangerous conditions working in factories, their vulnerability is highlighted, and they require protection. Traditionally, men have taken on the role of protectors, as far back as premodern times, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, as war pulls men away from home, women began to take on more and more of traditionally male roles in society. With men away at the front, women worked in factories and also perhaps take on the role of protector. We witness this in depictions of motherhood, in which mother’s physical proximity to their children is emphasized, a tactility highlighted.

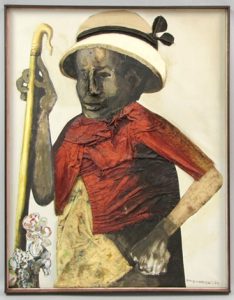

Women begin to legally and socially cement these wartime roles for peacetime during the 20th century, creating a new space for women in society. In the U.S., women win the right to vote in 1920, shortly after WWI. In 1960, the FDA approves the birth control pill, in 1963 Kennedy signs the Equal Pay Act, and in 1971 Bowdoin College, from whom we sourced most of the collection for this exhibition, began to matriculate women. As women become more full members of public society they begin to be seen not only as innate nurturers, good at feeding babies and making them laugh and keeping them alive, but also as role models. They begin to be seen as capable of passing down lessons, values, and ideas to their children beyond how to cook and clean. No longer simply idealized beauties who raise pretty children, or bodies who shield or sometimes die for their children, they become full people, role models rather than supporting players.

In this exhibition we categorize representations of mother into four signified themes, investigating the mother as idealized, mother as sacrificed, mother as protector, and mother as role model. Each allows us a glimpse at the evolution of Western visions of motherhood over time, and allows us to consider why motherhood signified these values at certain historical moments.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman and daughter with makeup), 1990, printed 2003, 20 in. × 20 in., platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman and daughter with makeup), 1990, printed 2003, 20 in. × 20 in., platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.