In Dorothea Lange’s efforts to capture the impacts of the Great Depression, she familiarized herself with Western farming culture in America and its response to the Dust Bowl. Lange advocated for social advancement and change to aid the suffering American during the 1920s and 30s. She also worked to publicize the success or failure of government agencies to uplift these rural families. In this image, Lange captures the difficulties of motherhood and nurturing children amidst economic and social disaster. Considering how the two daughters mirror the mother in dress and stance, Lange suggests the mother is a role model for her daughter, leading by example through difficult times. The daughters’ reflection of their mothers’ sustained femininity through dress reveals how the mother is specifically supposed to model femininity for her daughters.

A man leads his family of six through this barren, unforgiving landscape, and a few yards behind, a woman, seemingly the mother, wearily pulls her two children forward, suggesting the pressure and responsibility placed on mothers during these extraordinarily difficult circumstances. Given how far ahead the father is, it is clear that it is because of the mother that the children are keeping pace, not left behind. With scarce resources the Depression-era mother is meant to protect and nourish children, the hope of a better future.

The art historical canon is flush with images of mothers holding or carrying their children, but here all she can manage to do is pull them along, ushering in a new understanding of motherhood for common, working people that is characterized not by idealization but hard work, pain, and sacrifice.

This image has all the elements of what makes Sally Mann controversial. Mann is supposed to be a role model for her children, specifically her daughters. Allowing her daughter to pose naked and expose her body without shame, even if she’s just a child, suggests Mann is failing as a role model. Perhaps we can understand this as a criticism of how Mann is not setting a good example for how mothers are supposed to protect their children, something society expects and demands mothers to do. Critics accuse Mann of exploiting children by photographing them nude. Many attack Mann as a mother, claiming she has a responsibility to protect children from harm, in this case the eyes of the viewer.

The relationships between nudity, body, motherhood, and sexuality are all central themes in Mann’s work. Women are not supposed to be sexual beings but are expected to be mothers, an ironic contradiction rooted in oppression. When women are mothers, specifically when they are pregnant, their bodies are not regarded as sexual objects, but as holy vessels. Babies are often depicted in the nude, affirming that the presence of motherhood negates the sexuality of the body. As women move farther away from motherhood, they are no longer seen as sexually viable. In this image, the oldest woman is the most clothed, representing her sexual expiration. The other woman depicts the young mother figure, still sexually available as a mother and an object. The girl’s nudity symbolizes her eventual sexualization, noting the societal trajectory forced on women’s bodies, from the pureness of childhood, to the objectification as vessels and sexual beings, to the eventual discarding. The evolution of femininity, from generation to generation, in this photo signifies each mother modeling motherhood for her daughter.

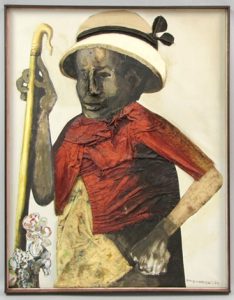

Benny Andrews grew up in the rural South of America in Plainview, Georgia to an impoverished family that worked on a cotton picking farm. In this piece Andrew depicts his mother with a cotton plant snaking up her cane, a nod to the family’s humble roots. Viola Andrews held her son in high regard his entire life and, against the odds, made all ten of her children go to school. This emphasis on education allowed Andrews to become the first in his family to graduate high school, as well as college. Andrews claims his mother emphasized education above all else, and as a sharecropper, pushed her children towards education as their way towards a better life. We see the representation of mother as a role model who overcame her own struggles to support her children.

Andrews depicts his mother as a strong, stalwart woman who, despite her slight frame, is not fragile but enigmatic, commanding. This is its own kind of idealization, but it is not her beauty that is emphasized, but her strength. She is admired for the way she protected and aided her family in overcoming unforgiving odds, and Andrew’s use of geometric forms lends her stature this solidity and strength. Andrews honors his mother as a role model and memorializes her as a strong woman who could do it all, while still fulfilling the societal expectations of motherhood.

This photograph is a part of Weems’ Kitchen Table Series. Weems chose to photograph herself and others sitting at her own kitchen table in an attempt to construct her own image, saying “I realized at a certain moment that I could not count on white men to construct images of myself that I would find appealing or useful or meaningful or complex.” Weems also suggests her body is a “stand-in” to represent all women. In this scene, the daughter mirrors the actions of her mother, presenting a younger and miniature reflection. The mirror in front of the mother is positioned toward the viewer, inviting us to join them and fill the empty seat.

Weems comments on the dynamic between femininity, motherhood, and the relationship between mother and daughter. As the daughter mimics the mother, she does not look to her senior for guidance. This suggests the transfer of femininity is innate. The mother serves as a role model for her daughter, teaching her to perform femininity and adopt the expected traits of the contemporary mother who can “do it all.”