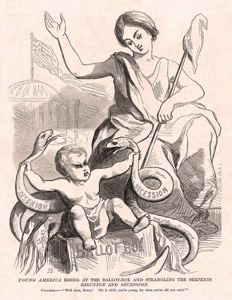

This engraving is attributed to 19th-century painter and printmaker Winslow Homer, although there are sources that cite an unnamed cartoonist as the artist. Regardless, the image was printed for mass distribution in 1860 and featured in Harper’s Weekly just weeks before the 1860 election and the outbreak of the Civil War. The cartoon alludes to the Greek myth of Hercules’ birth, upon which Hera sent snakes to kill Hercules. Homer imprints this story onto one of 19th century America, casting Hera as Mother America, a Statue-of-Liberty-esque woman who represents the bitter fragmentation of the country. Her snakes, “Disunion” and “Secession,” try to kill Hercules, who represents a “Young America,” or the American youth. The benign depiction of Hera reveals how the notion of America as strong and protected by her values is deceiving.

Young America encourages young people to vote and maintain the nation, and Homer seems to suggest that they will overcome the snakes of division. The quote at the bottom of the cartoon, “Well done, Sonny! ‘Go it while you’re young, for when you’re old you can’t,’” reveals the antagonistic dynamic between young and old. Suddenly far from the ideal, mothers represent the disillusioned and the fragmented. America’s mother figure is no longer a proud Lady Liberty, but a deceitful Hera, representing a fading way of life. This fading way of life signifies the youth leaving their immigrant roots and mothers behind so they may assimilate to American culture. It seems that mothers must make room for the new generation and sacrifice their past and future goals for the greater good. The children, rather than their mothers, are the future, empowered and accelerated by the American voting system.

William Holman Hunt, the founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, illustrates the beauty and fragility of life in this etching of his second wife, Edith, holding their child, Glady, above her arms in a moment of intensity. Set amongst columns and a domestic scene in the doorway behind, Hunt is alluding to the Renaissance— an era strongly associated with an appreciation of history paintings, particularly about the life of Jesus Christ.

Hunt, (especially during his time spent in the holy land of Jerusalem), regularly combined religious iconographies, alluding to classics and historical trends. Specifically, this etching echoes the familiar image of the Madonna of Humility, which are characterized by depictions of Mary seated on the ground. This kind of depiction is generally meant to highlight the piety, fragility, and volume of sacrifice of the Virgin. By placing common folk in a scene typically reserved for Christ, Hunt universalizes this sacrifice, suggesting perhaps that sacrifice and piety might, or should, characterize all good mothers. This advertent placement of undistinguished people in traditional poses of Christ and Mary was controversial yet somewhat typical of Hunt and his fellow Pre-Raphaelites.

Thought of as an atheist by many in his early life, Hunt is turning towards a more religious portrayal of family after losing his first wife, Fanny Waugh, during childbirth. Hunt portrays the sacrificial undertakings of the body that mothers endure during pregnancy and childbirth. Especially in times before medicine focused on maternity and female health, many women died in labor.

This piece by German artist Egon Schiele is part of a larger series of (dead) mothers and their children. Schiele depicts the tragic loss of a mother after childbirth, and the sacrifice women endure to bring in new life. This lifeless mother, etched in cool earthy tones, is contrasted by her newborn child who exudes life and warm, vibrant color. Schiele connects the figure of the mother and child through technique and attention to subject matter. Schiele often used his mentor, Auguste Rodin’s, technique of continuous drawing, maintaining the connection between pen and paper, and artist and subject. Remnants of this technique are visible within this piece, as Schiele connects the bodies of mother and child through the curved, fluid lines of the blanket

Schiele imagines the remorse and sadness of a mother who has to leave her child so soon after bringing them into this world. The lack of clear distinction of the separate bodies of mother and child also highlights their unparalleled bond.

Created four years before WWII, the piece seems a darker take on motherhood, perhaps betraying the tremors of a society on the verge. Inaugurating a century characterized by tremendous loss and enormous sacrifices of everyday people, this piece envisions a future with a lifeless mother, more a memory or lost potential of motherhood than the thing itself.

In Dorothea Lange’s efforts to capture the impacts of the Great Depression, she familiarized herself with Western farming culture in America and its response to the Dust Bowl. Lange advocated for social advancement and change to aid the suffering American during the 1920s and 30s. She also worked to publicise the success or failure of government agencies to uplift these rural families. In this image, Lange captures the difficulties of motherhood and nurturing children amidst economic and social disaster. Considering how the two daughters mirror the mother in dress and stance, Lange suggests the mother is a role model for her daughter, leading by example through difficult times. The daughters’ reflection of their mothers’ sustained femininity through dress reveals how the mother is specifically supposed to model femininity for her daughters.

A man leads his family of six through this barren, unforgiving landscape, and a few yards behind, a woman, seemingly the mother, wearily pulls her two children forward, suggesting the pressure and responsibility placed on mothers during these extraordinarily difficult circumstances. Given how far ahead the father is, it is clear that it is because of the mother that the children are keeping pace, not left behind. With scarce resources the Depression-era mother is meant to protect and nourish children, the hope of a better future.

The art historical canon is flush with images of mothers holding or carrying their children, but here all she can manage to do is pull them along, ushering in a new understanding of motherhood for common, working people that is characterized not by idealization but hard work, pain, and sacrifice.

Elinor Carucci, a young Israeli-American mother of two, here depicts herself rushing across a street with her two children in a photograph taken by a trained assistant. The piece is is part of a series of photographs in a book she created called Motherhood, which shows her intimate, and at times difficult relationship she has with her children.

Here, Carucci clutches one of her children, and though mother-holding-child is a recognizable trope in the art historical canon, the way she holds her, unaware of any viewer and only for practicality’s sake–her child certainly could not keep her brisk pace by walking beside her–is new, illustrating the fast pace of contemporary life and the working woman’s role in it. In a society that expects good mothers to raise their own children but also demands that all productive members of society work, Carucci seems faced with the dilemma of bringing her children with her or leaving them behind. Notably, she cannot carry them both, and the shadow of her son chases after her, reaching out to be in her arms. In 2010, it seems to be a mother is to make sacrifices.