Felix Gonzalez-Torres – “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)

Catherine Opie – Self-Portrait

Laura Aguliar – Nature Self-Portrait #11

Del LaGrace Volcano – Me Myself and Eye

Judy Chicago – Pasadena Lifesavers: Blue Series #2

Reni, Guido (possibly after). Salome with the Head of John the Baptiste. 1500-1700. Oil on canvas. 23 in. x 30 in. (58.72 cm. X 76.2 cm.) Bequest of the Honorable James Bowdoin III.

Despite ignoring the violence of a decapitation and the vulgarity of a seductive dancer, Reni’s deliberate understatement of such a scene is nearly just as lewd. Salome has bright blushing cheeks that match the rich, almost moving folds of her silks. She is the definition of life, especially in comparison to the near-blue color and numbness of St. John the Baptist’s bloodless face. His head becomes another object, detached from both his body—a symbol for his holiness as saints do not bleed viscera like regular mortals and for the destruction of ill-behaved women like Salome.

While there is uncertainty regarding the exact date and origin of the painting, it is in step with it’s Renaissance contemporaries in it’s representation of Salome as an Eve-like courtly lady. Rather suggestively, it bears striking resemblance via nonchalant but presenting pose, bespoke and turbaned attire, and physical likeness to Salome with the Head of John the Baptist by Circle of Guido Reni. While the attempt of Renaissance artists to erase Salome’s canonical sexuality by transforming the dancer into a courtly lady, they only succeed in sublimating it. This is, in part, because at the time, the rise of the merchant class saw a flood of instructional content—everything from explicit instruction manuals to didactic literature. Art becomes a method of both inducing and signaling moral, (and often gendered) virtues. In understating her sexuality, the artists reinforce the idea that female sexuality is so unspeakable that the decapitated head of a saint is more appropriate for viewing. Salome is a warning sign, warding off women from temptation and returning their focus to their own modesty.

Sources:

Jordan, William Chester. “Salome in the Middle Ages.” Jewish History, vol. 26, no. 1/2, 2012, pp. 5–15.

Karasick, Adeena. “Salomé: Woman of Valor.” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 26, 2014, pp. 147–57. JSTOR, doi:10.2979/nashim.26.147.

Kultermann, Udo. “The ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’. Salome and Erotic Culture around 1900.” Artibus et Historiae, vol. 27, no. 53, 2006, pp. 187–215. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/20067116.

Long, Jane C. “Dangerous Women: Observations on the Feast of Herod in Florentine Art of the Early Renaissance.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 4, 2013, pp. 1153–205. JSTOR, doi:10.1086/675090.

Reni, Guido Salome ||| Old Master Paintings ||| Sotheby’s L10035lot5tq8zen. https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.92.html/2010/old-master-and-british-paintings-l10035. Accessed 21 Dec. 2020.

Rodney, Nanette B. “Salome.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 11, no. 7, 1953, pp. 190–200. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/3257597.

Botticelli, Sandro, Portrait of a Lady (“Simonetta Vespucci”), 1480-1485, 32 x 21 in. (82 x 54 cm), tempera on wood, Stadel Museum, Frankfurt.

Sandro Botticelli, a leading Florentine painter of the Early Renaissance excelled at creating portraits of mythological creatures and scenes. In Portrait of a Lady, also known as Idealised Portrait of a Lady, Botticelli portrays a beautiful young nymph dressed in a fantastical wardrobe. The elaborate and embellished wardrobe of the woman includes magnificent ribbons, feathers, lace and beads detailed in her dress, jewelry and hair. Botticelli sexualizes the woman’s appearance through her long braids that fall on her chest. Furthermore, the nymph is not making direct eye contact with the viewer which makes her more desirable; Botticelli challenges the strict profile portraiture style by offering a glimpse of the young lady’s left eye and slightly positioning the young lady towards the viewer to emphasize her chest. The nymph wears a large medallion, believed to be Nero’s Seal, which belonged to powerful Italian statesman, Lorenzo de’Medici. Nero’s Seal depicts the mythological legend of the musical challenge between Apollo (God of Music and Sun) and satyr, Marsyas; the presence of Nero’s Seal further emphasizes the lady’s status as a beautiful mythological creature.

Scholars argue that the young nymph is actually an idealized portrait of Simonetta Vespucci who was known to be one of the most beautiful women in Florence during the Early Renaissance period. Historians contend that Botticelli was madly in love with Vespucci.

Sources:

Gabriela. “Sandro Botticelli – Portrait of a Young Woman (1480 – 1485).” Artschaft, 17 Jan. 2018, artschaft.com/2018/01/17/sandro-botticelli-portrait-of-a-young-woman-1480-1485/.

“Portrait of a Young Woman.” Portrait of a Young Woman by Sandro Botticelli, 2018, www.sandro-botticelli.org/portrait-of-a-young-woman/.

Saar, Alison, Girl with a Pearly Earring, 2018, 15 × 12 in. (38.1 × 30.5 cm), print, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

Made over three hundred and fifty years after Vermeer’s portrait of a slightly different name, this Alison Saar piece completely contrasts that of the Dutch master. Instead of an unnamed girl, Saar depicts Topsy, a character from Harriet Beacher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Topsy, a notoriously mischievous girl who often represents the opposite of ‘white goodness’, is a stereotype of a young and wild Black girl. Saar includes portraits of Topsy in a lot of her works, often in sculptures that contrast classical Greek statues, taking this stereotype and turning it on its head. She does so in this piece, evoking strong feminist themes but also an intersection with Blackness. Topsy was accused of stealing things, including earrings. Here, she wears her own, but holds up another as if to say, ‘hey, are you looking for this?’

In contrast to the fancy Oriental attire that Vermeer depicts his subject with, Saar depicts Topsy here with just a bare tank top. We see her collarbone, breasts, and nipples, yet she does not seem concerned. Even though Saar uses straight, hard lines to indicate shadow, she does so to create a perceived softness in other parts of Topsy’s skin. There is a nuanced balance; Topsy confronts us unapologetically, but also exudes a soft playfulness.

Work cited:

Tales Of The Unconfined: Alison Saar’s Defiant Women Warriors

Vermeer, Johannes, Girl with a Pearl Earring, 1665. 44.5 cm × 39 cm (17.5 in × 15 in), oil on canvas. Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands.

Veering from the majority of Vermeer’s works that depicted intimate scenes of daily Dutch life, this painting from the Dutch master brings us eye to eye with the subject. Often called the Mona Lisa of the North, it technically is not a portrait at all. It is a tronie, a painting style of the time in the Netherlands that showed a character or specific type of person with an exaggerated expression. The dark background and soft lighting helps to further the mysteriousness of the unnamed girl. Notice the softness of her facial features, and how the edges of her lips and her eyes do not come to a specific point; they are somewhat blurred. Does she smile at us? Or perhaps the opposite? It is up to us; Vermeer encourages the viewer to project their emotions onto the figure.

Under the surface, there is a deeper connection in this painting between wealth, colonialism, and an unidentified woman. The white girl wears a pearl, indicating wealth, and a turban that signifies the success of Dutch colonialist trade routes. Vermeer combines a lust for material affluence with longing for ‘the Orient’, all embodied in a tronie that evokes a desire for a mysterious, unidentified female body. It is a beautiful painting, but its evoked fantasy objectifies an idea of a woman who remains unnamed.

Work cited:

https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/explore/the-collection/artworks/girl-with-a-pearl-earring-670/

Raphael, La Fornarina, 1518-1519, 33 in × 24 in. (85 cm × 60 cm), oil on wood, National Gallery of Ancient Art, Rome.

The great artist Raphael was known for his love of sex. While working in Rome, he found his muse, Margherita Luti, and painted a portrait to commemorate her beauty.

Margherita is outfitted in draping red and translucent fabric, her pale breasts exposed in the harsh white light. She dons a coordinating oriental hat and armband, suggesting a degree of wealth as a result of her association with Raphael. Her armlet reads “RAPHAEL URBINAS” in gold letters. While her chest is ghostly white, Margherita’s face is flushed red with heat. Her left hand rests in her lap, while her right hand is drawn under her left breast.

This eroticized painting of a male artists’ muse is a theme stretching across centuries of portraiture. Studios are a male-dominated space where artists have artistic and sexual control over models. Carol Duncan notes that females in portraiture “usually appear as personal possessions of the artist, part of his specific studio and objects of his particular gratification.”

Margherita’s hand placement over her breast and her groin has strong sexual implications. Raphael claims ownership of his muse by posing her in the nude, but also by dressing her in expensive accessories, and depicting her in an armband with his name stitched in gold.

Sources:

“Biography of Raphael.” Raphael Biography | Life, Paintings, Influence on Art, 2002, www.raphaelsanzio.org/biography.html.

Duncan, Carol. “Virility and Domination in Early Twentieth-Century Vanguard Painting.” Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany, edited by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, Harper & Row, 1982, pp. 293–313.

Penny, Nicholas. “Raphael.” Grove Art Online. 2003. Oxford University press. Date of access 2 Dec. 2020, <https://www-oxfordartonline-com.ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000070770>

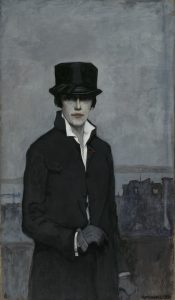

Romaine Brooks, Self-Portrait, 1923, oil on canvas, 46 1⁄4 x 26 7⁄8 in. (117.5 x 68.3 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the artist, 1966.

Born into a wealthy American family yet suffering a difficult childhood, Brooks moved to Europe in 1893, at the age of 19. As a gay woman in the early 1900s, she spent much of her time in Paris with other wealthy queer people, particularly those who fled England after the Oscar Wilde trials, when the famed writer was imprisoned for being gay. In this self-portrait, part of a series she painted of women in her social circle, Brooks subverts typical portraiture by challenging what it means to wear clothing that is coded to a gender other than one’s own. She wears a riding outfit and top hat, both signifiers of aristocratic masculinity, and juxtaposes these with feminine facial features and lipstick (notice how she makes that bright red pop by contrasting it to the subdued urban background).

This combination of the feminine and masculine replicates androgynous identity that was popular among many women in the 1920s. Does Brooks vouch for an identity formed of both feminine and masculine aspects, or does she indeed reject the validity and necessity of these codifications of gender altogether? Either way, Brooks asks questions of traditional representations of gender that still resonate almost a century later.

Work cited:

https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/self-portrait-2916

Unknown Artist, Maybe She’s Born With It, n.d. print on paper 18 in. x 24 in. (45.72 cm x 60.96 cm) Bequest of David P. Becker, Class of 1970 2011.69.375

There is little known about this print besides its name: Maybe She’s Born With It. The inclusion of those five words drastically changes the interpretations and meaning of the background image. Without the slogan, the print depicts a woman in a burqa, perhaps open to religious analysis, however, with the slogan, the woman in a burqa is meant to be viewed through an entirely different lens: that of Western beauty standards.

Maybelline came up with this famous tagline in 1990, and by 2013, it was declared “the most recognizable strapline of the past 150 years.” The common phrase is associated with a flawless white woman’s face. The woman upholds all of the stereotypical beauty standards, displays confidence, and shows some skin. The woman depicted in this print is quite the opposite. She is slouched over with sad, tired eyes, which are her only exposed feature.

Juxtaposing the Middle Eastern woman with the famous Western slogan serves multiple purposes, the most important of which is to highlight the exclusivity of the West’s beauty standards. These signifiers of beauty have been created and refined by men and have been present in art for centuries, leaving millions of women feeling neglected.

Sources:

Parsons, Russell. “Maybelline’s ‘Maybe She’s Born With It’ Strapline ‘Most Recognisable’.” Marketing Week, 16 Sept. 2013, www.marketingweek.com/maybellines-maybe-shes-born-with-it-strapline-most-recognisable/.

Gentileschi, Artemisia. Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandra. 1616. oil on canvas. 71.5 cm × 71 cm (28.1 in × 28 in). Located in the National Gallery, London.

Artemisia Gentileschi, an accomplished Italian Baroque female artist of the seventeenth century, portrays herself as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a Christian saint persecuted for defending her faith. During her career, Gentileschi painted many portraits of herself in the guise of strong female characters. Scholars argue that this pattern highlights Gentileschi’s resilience and self-promotion as an artist. At the age of seventeen, Gentileschi endured a prolonged trial against her rapist, Agostino Tassi. Tassi served as Gentileschi’s mentor. Gentileschi experienced brutal physical and psychological torture as she testified. Through the disguise of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Gentileschi alludes to her strength and perseverance that she exhibited during the trial.

Gentileschi illustrates Saint Catherine of Alexandria as courageous as she faces her dark fate. Under the reign of Maxentius, he commands Saint Catherine of Alexandria to death by spiked wheel. In the portrait, her body and left hand grasps the spiked damaged wheel which symbolizes her torture and death. The saint’s right hand clasps a palm branch which signifies martyrdom. In the portrait, Gentileschi’s application of dramatic lighting is prevalent as the light illuminates the spiked wheel and the fair skin of Saint Catherine of Alexandria.

Sources:

“Artemisia Gentileschi: Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria: NG6671: National Gallery, London.” The National Gallery, The National Gallery, www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/artemisia-gentileschi-self-portrait-as-saint-catherine-of-alexandria.

Patricia Simons, “Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders (1610) in the Context of Counter-Reformation Rome,” in Artemisia Gentileschi in a Changing Light, ed. Sheila Barker (London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publications, 2017): 41-58.

Sherwin, Skye. “Artemisia Gentileschi’s: Self-Portrait as St Catherine of Alexandria.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 8 Mar. 2019, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/mar/08/artemisia-gentileschi-self-portrait-as-st-catherine-of-alexandria-brutally-seeking-vengeance.

Titian. Venus of Urbino. 1534. Oil on canvas. 119 cm × 165 cm (47 in × 65 in). Located in Uffizi, Florence.

One of Titian’s greatest masterpieces, Venus of Urbino depicts Venus, the goddess of love, sex, and beauty, as a sensual figure gazing into the viewer’s eyes. Commissioned by the Duke of Urbino Guidobaldo II Della Rovere, this work served as a present to his betrothed, displaying how she would be expected to behave in their marriage. The painting itself represents the allegory of marriage, with the dog curled at Venus’s feet a symbol of fidelity and the woman and child in the background as a symbol of motherhood.

Venus herself reclines on a dark red cushion covered in a bright white sheet. Her pale body is encircled by a halo of white, representing her purity and perfection. Her gaze is piercing while her face remains soft, creating a sultry, lustful look that captivates the viewer. She lays back, her neck and shoulders relaxed submissively, prominently exposing her naked figure. Though her legs are crossed, her hand rests on her genitals as an overt cue to the viewer that she is a sexually mature woman, even insinuating that she is masturbating, scholars argue. In this work, Titian has created the quintessential renaissance woman, one of beauty, purity, and fidelity on display for all to see.

Sources:

“Venus of Urbino by Titian at Uffizi Gallery Florence.” Visit Uffizi, www.visituffizi.org/artworks/venus-of-urbino-by-titian/.

“Venus of Urbino by Titian: Artworks: Uffizi Galleries.” By Titian | Artworks | Uffizi Galleries, www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/venus-urbino-titian.

Johnston, Alfred Cheney. Julie Newmar. n.d. vintage photograph. 12 1/8 x 10 3/8 in. (30.8 x 26.35 cm). Gift of Francis A. DiMauro 2013.4.28

During the early 1900s, failed portrait painter-turned-photographer Alfred Cheney Johnston became known for his famous photographs of Broadway’s favorite girls: Ziegfeld’s Follies. His intriguingly sexualized depictions of these young, beautiful, successful Broadway women landed his name in Vanity Fair and made him quite well-known. As his career developed, he was recognized as one “of the creators of 20th century glamour photography, giving his sitters erotic allure while vesting them with dignity and power.”

As a so-called creator of glamour photography, he was catapulted into the celebrity realm. In 1950, he photographed rising actress Julie Newmar. Julie was 16 or 17 years old when the photograph was taken. Despite her young age, she is depicted very in a sexual light. She is reclining in her chair, similar to the pose seen in Venus of Urbino and other traditional Renaissance portraiture, however, she is clothed and brings a 20th century edge. Her perfectly done makeup highlights her high cheekbones, plump lips, and small, straight nose. Julie embodies the stereotypical qualifications for beauty: young, fair skin, perfect facial features, wealthy, and sensual, but not scandalous. Her personification of the timeless beauty standards allows Johnston to represent her with such “erotic allure.”

Sources:

Shields, David S. “Alfred Cheney Johnston.” Broadway Photographs, www.broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/alfred-cheney-johnston.

I Framed My Breast for Posterity. Cibachrome print. 19 5/8 in. x 27 1/2 in. (49.85 cm x 69.85 cm). Gift of Jo Spence Memorial Archive. 2001.18.10

The female nude has not historically provoked empathy, but that is the beginning of what Jo Spence accomplishes in this self-portrait. Spence, a british feminist who was renowned for her work focusing on ‘women’s work’ and it’s various forms in public and private spaces, took the photo as part of a series documenting her struggle with breast cancer. The title reveals all— the threat of a full mastectomy, the reality that her body, her breasts and her womanhood were to be forever altered and her profound sense of purpose.

From the title, which compels us to ask ‘for whose prosperity? why?’, to the fact that it is a self-portrait, there is no escaping her reclamation of her own body as a medium for her art or the assertion of her identity as artist over that of a patient or a woman. She is nude but the photo is nostalgic and clinical rather than strictly sensual. Spence may strike a vulnerable pose with closed eyes and hidden mouth, she is not being ‘looked upon’; she is deliberate with and responsible for every detail, each of which read like parts of one-half of a phone call. Her breasts hang heavy— asymmetrical, unevenly lit and bandaged unlike those of the Venus which are defined by faint shades and pale colors.

She depicts her breasts and thus herself not as an object for the viewing pleasure of others like Venus but a proper body of flesh that is vulnerable to illness, both vital to her life and marred by it. She questions then what it means to value her breasts as part of her body rather than an object of sexual titillation and ultimately, what it means to be a woman.

Sources:

Bell, Susan E. “Photo Images: Jo Spence’s Narratives of Living with Illness.” Health, vol. 6, no. 1, 2002, pp. 5–30. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26646406. Accessed 21 Dec. 2020.

Xiuwen, Cui. Angel No. 2. 2004. Photograph on paper. Gift, Joe Baio Collection of Photography. 2017.61.9. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

Cui Xiuwen, a revolutionary contemporary artist from China examines gender, sexuality and pregnancy through various platforms such as oil paintings, video and photography. As an impactful feminist artist, Cui Xiuwen reveals the anxieties and concerns of young pregnant Chinese women through the photograph, Angel no.2. Angel no. 2 is a photograph that captures twelve images of the same teenage girl who is positioned in a horizontal pattern. Cui Xiuwen challenges traditional portraiture by utilizing multiple images of the same teenage girl. The teenage girl is dressed in a white dress with bright red eyeshadow and lipstick. Through this feminine composition, Ciu Xiuwen emphasizes their doll-like features. Cui Xiuwen positions the subjects in differentiated and uncomfortable postures; the twelve girls are falling off the chairs while accentuating their pregnant bellies. The dramatic positioning of the teenage girl examines the relationship between control of the body (or lack thereof) and pregnancy.

The uncomfortable positioning and depressing facial expressions of the teenage girls alludes to greater anxieties in regard to gender and sexuality ideologies within China. Chinese ideologies such as population control and disapproval of female sexuality generate concerns for contemporary Chinese women. Cui Xiuwen further addresses Chinese womens’ suppression as the backdrop of the print is a location that resembles the Forbidden City in Beijing, China; the Forbidden City is a symbol of a suppressive, conservative and patriarchal society.

Sources:

“Cui Xiuwen.” Brooklyn Museum: Cui Xiuwen, Brooklyn Museum, www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/about/feminist_art_base/cui-xiuwen.

Lin, Sabrina. Object of the Month: Cui Xiuwen, “Angel No. 2,” 2004. Bowdoin College of Art Museum, www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum/news/2019/object-of-the-month-cui-xiuwen,-angel-no.-2,-2004,.html.

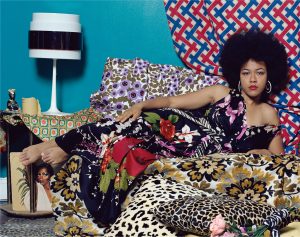

Thomas, Mickalene. Tell Me What You’re Thinking. 2016. Chromogenic print on paper. 39 3/4 x 49 1/2 in. (100.97 x 125.73 cm). Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund. 2018.8

Tell Me What You’re Thinking is a modern photograph by Mickalene Thomas, a contemporary multi-media artist who focuses on highlighting identity and representation of black women. Thomas herself is a queer black artist producing a body of work that intentionally places black women in spaces where previously they have been absent, empowering them in a genre where they have been historically exploited. She draws inspiration from the canon of European art in much of her work to highlight misogynistic tropes and turn them on their heads, updating female subjects to modern women.

Tell Me What You’re Thinking portrays a black woman reclining on a bed, surrounded by a multitude of loud, clashing patterns, looking the viewer directly in the eyes. Thomas is highly interested in fashion, and her choice of patterns are wild and distracting from the woman, as if to say that this woman is not reclining for the viewer’s pleasure and as such she will not be so easily digestible. The woman, though reclining, is sitting straight, her shoulders square to the viewer and head held tall. Her hair is styled in an afro and the table is adorned with tokens of Black culture, which is another way that Thomas is reversing the erasure of this culture and reintroducing it into the art historical narrative.

Sources:

“Mickalene Thomas: Origin of the Universe.” Brooklyn Museum: Mickalene Thomas: Origin of the Universe, 2013, www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/mickalene_thomas/.

“Mickalene Thomas.” Mickalene Thomas – 119 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy, www.artsy.net/artist/mickalene-thomas.

Back to Gallery

Saar, Alison, Blue Plate Special, 1993. Colour transfer lithograph and etching (soft-ground) with chine collé. Sheet: 24 x 24 inches (61 x 61 cm). Purchased with the Hunt Corporation Arts Collection Program, 1994.

Saar, Alison, Blue Plate Special, 1993. Colour transfer lithograph and etching (soft-ground) with chine collé. Sheet: 24 x 24 inches (61 x 61 cm). Purchased with the Hunt Corporation Arts Collection Program, 1994.

Given only a quick glance at her expression, it might seem like she’s only sleeping, but the reality of the etching is much more gruesome. A blue head, tilted slightly towards the viewer, lies in a white dish that sits on a low, black table. Wreathing the bowl is a long hand towel that had once guarded someone’s hands from the plate’s heat before being forgotten. The title ‘Blue Plate Special’ is a phrase historically used to refer to a cheap meal offered at North American diners, often part of the daily selection and served on pre-divided plates, but is at odds with the off-hand tone of the print. The ‘blue’ refers to the plate and the decapitated head of a nameless black woman and the title to a diner setting and a lonely, low table that is almost a stool, a meal and a body that is not a body. The head is offered up as a source of nourishment and an object to be taken apart and consumed— Saar literally represents the black female body, mind and very being (as represented by her head, the home of one’s personality, knowledge and humanity) as some strange fruit: of value but forgotten about, gruesome but bloodless, used but unwanted. That this woman is without a body, name or identity further flattens her; she is not an individual but rather a stand in for African American women at large, who permanently live in such liminal spaces.

Saar is well-known for this doublespeak; the re-appropriating of everyday objects, referred to as ‘found objects’, to offer many new and often conflicting meanings. Her depictions of the black body are almost never in earnest but rather ironic; black bodies are never in full but disembodied and decapitated. She said herself that the “floating heads may also be an act of denial of the self”. She is unable to render the black body fully as our ‘found objects’, given meaning by their history, are incapable of providing enough nuance.

Sources:

Farrington, Lisa E. “Reinventing Herself: The Black Female Nude.” Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 24, no. 2, 2003, p. 15. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2307/1358782.

Reclaiming Histories: Betye and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood. 2020, p. 41.

Schur, Richard. “Post-Soul Aesthetics in Contemporary African American Art.” African American Review, vol. 41, no. 4, Dec. 2007, p. 641. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2307/25426982.

Back to Gallery Martine Gutierrez, Demons, Tlazoteotl ‘Eater of Filth,’ p92 from Indigenous Woman, 2018, C-print mounted on Sintra, hand-painted artist frame. 41 1/2 x 28 1/2 x 1 1/2 in. (105.41 x 72.39 x 3.81 cm). Museum Purchase, Greenacres Acquisition Fund. 2019.43

Martine Gutierrez, Demons, Tlazoteotl ‘Eater of Filth,’ p92 from Indigenous Woman, 2018, C-print mounted on Sintra, hand-painted artist frame. 41 1/2 x 28 1/2 x 1 1/2 in. (105.41 x 72.39 x 3.81 cm). Museum Purchase, Greenacres Acquisition Fund. 2019.43

Tlazoteotl is an earth goddess of the Aztecs who both encouraged and cleansed people’s immoral behavior. Literally translated, ‘Tlazoteotl’ means ‘Filth Diety’ which captures both facets of her domain: inciting “filthy” behavior, typically sexual, and subsequently punishing it. She is often portrayed with blackened lips, representing the dirt that she consumes in her role of “eater of filth.” Gutierrez chooses to represent that filth as a black line that trails down her chin, originating in her mouth. That black appears again under her eyes, here representing both those sins that she consumes as well as the tears that she may shed for those sinners. Showing mercy, she would offer people one chance within their lifetimes to confess their sins in a complex ritual involving the offer of molten gold, represented in this work by her golden shoulders and hands.

When considered alongside Gutierrez’s other works in this series, much of the adornment covering Tlazoteol functions as a criticism of colonization, as she now bears what was sought after by those conquerors who laid waste to Aztec land which, in effect, purifies their sin. Here, Gutierrez depicts herself as Tlazoteol, breathing new life into the story of the goddess. Gutierrez, a bi-racial queer woman, focuses on identity as a form of art rather than something reduced to a few descriptive words. She is as she presents herself, not as we choose to describe her.

Sources:

Mansur, Reid. “Tlazoteotl, Eater of Filth.” Martine Gutierrez’s “Demons” and the Queer Latinx Experience, 2019, scalar.usc.edu/works/martine-gutierrezs-demons-and-the-trans-latinx-experience/tlazoteotl-eater-of-filth.

Mingren, Wu. “Tlazolteotl: An Ancient Patroness and Purifier for All Things Filthy.” Ancient Origins, Ancient Origins, 20 July 2018, www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-americas/tlazolteotl-0010400.

“Martine Gutierrez.” RISD Museum, 2018, risdmuseum.org/art-design/collection/demons-tlazoteotl-eater-filth-p92-indigenous-woman-201941.