The Bowdoin College Museum of Art is home to a series of ancient Assyrian stone panels, one in particular which is the focus of this webpage. Studying the relief and its context reveals two controversies—one thousands of years ago, and the other just about 180 years ago. By looking at the controversies and audience responses to the memorial across time, we can look at the memorial in a new light.

The panels are huge, and date back to more than 2,500 years ago. They were discovered during an excavation of the ancient city of Kalhu, the capital city built by Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II. The palace was excavated by a Brit named Austen Henry Layard, who secretly stole the discoveries in hopes that they were of the Biblical city Nineveh. Bowdoin Professor James Higginbotham describes the local controversy surrounding Layard’s excavation in a 2007 New York Times article: “It’s possible the locals were not happy Layard was there… his tools were taken and he kidnapped a man to get them back.” Evidence seems to indicate that Layard made enemies out of the people living in what is now Iraq by stealing their artifacts. The specific relief pictured above was claimed by Dr. Henri Byron Haskell, a Bowdoin alumnus who took it form Kalhu and shipped it back to Bowdoin.

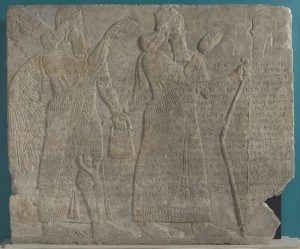

Only more recently, in the mid 2000s, did Bowdoin’s curators discover indications of another controversy: the carving’s disfigurements, crudely repaired with plaster filling. The relief is an image of King Ashurnasirpal II, but closer inspection reveals slashes in the stone across his bow, his wrist, and his ankles. The curators have concluded that members of the Medes tribe likely disfigured the image of Ashurnasirpal specifically as a symbolic gesture against the king who had subordinated their tribe 200 years prior. We can only guess what these specific disfigurements were intended to communicate, but we can grasp the broader idea—the Medes were intentionally seeking symbolic revenge against the king’s power, two centuries later in retrospect.

These two controversies surrounding the relief of Ashurnasirpal illuminate the context of the commemoration. By studying the response from both modern Iraqis and ancient Medes to the monument, we can deepen our understanding of the world in which it was discovered, and in which it was created. In ancient times, the Medes were deliberate in how they chose to disfigure the commemorative monument, weakening the power of a monument originally intended to communicate that power. In more modern times, the local Iraqis fought against imperialist archaeologists stealing their history. Looking at the monument on its own reveals little information, solely about Ashurnasirpal and his society. However, if we instead focus on the stories of controversy and audience reaction to the monument, we gain a better understanding of how the commemoration itself was intended, and subsequently received.

References

Moonan, Wendy. “Assessing the Wounds of an Ancient Assyrian Ruler,” The New York Times, 31 Aug 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/31/arts/design/31anti.html?ex=1189224000&en=d67792373663979f&ei=5070&emc=eta1. Accessed 23 May 2021.

Porter, Barbara N. Assyrian Bas-reliefs at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College, 1989.

“Relief Timeline,” Bowdoin College Museum of Art. bowdoin.edu/art-museum/exhibitions/2016/timeline.html. Accessed 23 May 2021.