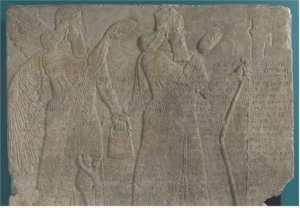

On display in Bowdoin College’s Museum of Art are several Assyrian Reliefs that were carved more than two thousand years ago. Originally excavated from the ancient city of Kalhu, located in modern day Northern Iraq, they were donated to the college by Dr. Henri Byron Haskell— a Bowdoin alumni. The relief is one of two hundred panels resected from the ruins of the Northwest Palace that the Assyrian King Assurnasirpal commissioned. This particular relief depicts a winged deity gifting the Assyrian King with what has been interpreted as a fertile gift.

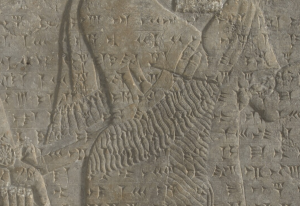

However, covering the relief is a lengthy message written in cuneiform, which has come to be known as the ‘standard-inscription.

Written by King Assurnasirpal, the standard inscription is an autobiography that details the triumphs of the mighty ruler. Below is an abbreviated translation of a section from the inscription that details his efforts in rebuilding the city of Kalhu.

“I rebuilt the city [of Kalhu]. I took people which I had conquered from the lands

over which I gained dominion. […] I settled them therin. I cleared away the old

ruin hill [and] dug down to water level. I sank [the foundation pit] down to a depth

of 120 layers of brick. I founded therin a palace of cedar, cypress, […] and tamarisk

as my royal residence for my lordly leisure for eternity. […] I decorated it in a splendid

fashion I surrounded it with knobbed nails of bronze. I hung doors of cedar, cypress,

dapranu-uni, and meskannu-wood in its doorways. I took in great quantities and put

therein silver, gold, tin, bronze, iron, booty from the lands over which I gained dominion.”

Porter, Barbara (1989). “Assyrian Reliefs at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art” Accessed May 9, 2021, https://www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum/pdf/Assyrian%20Bas-reliefs%20at%20the%20Bowdoin%20College%20Museum%20of%20Art.pdf

Bowdoin College, Art Museum. Explore Ancient Assyrian Reliefs. Accessed May 9, 2021, https://www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum/education/young-learners/assyrian.html