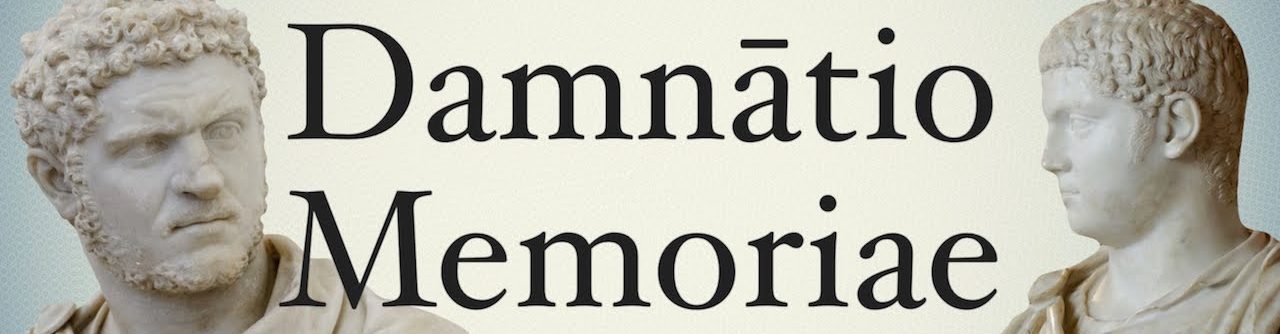

Figure 1. Example of Damnatio Memoriae in Rome where an emperors’s image was disfigured on a coin in an attempt to erase any trace of the individual (Forvm Ancient Coins).

Everything we learn about the past through history, artifacts, or oral tradition has been carefully crafted by those of the time. How one will be remembered has been a topic of interest of several societies including the Romans. The Romans, however, did not only add their stories to the histories, but they removed them too. In a practice known as Damnatio Memoriae, the Roman government would set out to condemn the memory of a person and, in this way, erase the person from the histories. By this order, the person was written out of inscriptions, their images were disfigured and destroyed, and even their homes could be taken down. Although this practice was directed at “enemies of the state”, emperors were also common targets of the practice and the ramifications of the practice towards these men were even more severe. Throughout Roman history, a total of 26 emperors were victims of this practice and in addition to what has been said, these emperors’ laws could be overturned as well as any coins with their faces recalled (Figure 1).

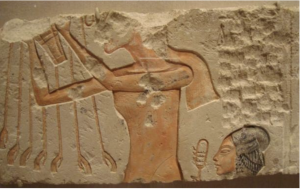

Figure 2. Relief from Ancient Egypt circa 14th century BC depicting King Akhenaten and his daughter. The relief has been defaced as evidence of his successors attempt to condemn his memory (Neil R/ CC BY NC 2.0 ).

While this practice was an aspect of the Roman Republic and Empire, similar practices have been seen across place and time. The Ancient Egyptians, for example, also attempted to condemn a person’s memory in the removal of Akhenaten circa 1300 BC, “The Heretic King”, wherever he was mentioned or pictured (Figure 2). Chosen to be forgotten due to his religious upheaval of Ancient Egypt, Akhenaten was only added to the history in the 19th century due to the thorough job his successors did to condemn his memory. The official act of forgetting has also been seen in modern times. An example of this happened in 2011 when President Hosi Mubarak of Egypt was removed from office and his name, as well as his wife’s, was removed from all official Egyptian Monuments.

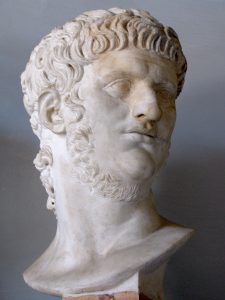

Figure 3. Bust of Emperor Nero of Rome from 1st century CE. An example of how despite the efforts to condemn his memory, his image and name persisted throughout history (Italofile).

These attempts to condemn a person’s memory were not as one might think. The most obvious evidence of this is that we know and learn about many of the individuals who were subject to this practice. Nero, arguably one of the most prominent figures in Roman history, has always been a common topic of discussion in the classroom despite being a victim of Damnatio Memoriae (Figure 3). Moreover, the fact that Rome wanted to permanently censure any trace of Nero only adds to his memory and history.

A recurring theme in the aftermath of any variation of Damnatio Memoriae is that instead of diminishing a person’s history, the practice actually supplements it by adding curiosity and mystery to the circumstances surrounding this person’s “forgetting”. Moreover, the condemners never truly intended for the victims of Damnatio Memoriae to be forgotten, but rather remembered for the dishonor that was bestowed upon them. An examination of Geta and Caraculla of Rome, King Ashurnasirpal of Assyria, and Jefferson Davis’s history with Bowdoin will be illustrated to further the point that the attempted removal of commemoration only amplifies a person’s place in history with the true intention of them being remembered as a victim to this practice.

References:

“NumisWiki – The Collaborative Numismatics Project – Thousands Of Online Numismatic Books, Articles And Pages. Damnatio Memoriae.” Forum Ancient Coins, www.forumancientcoins.com/numiswiki/view.asp?key=Damnatio+Memoriae.

Flower, Harriet, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace & Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

Gill, N. S., 2014. Damnatio List. [Online] Available at: http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/romannames1/a/EmperorsErased.htm

Lendering, J., 2006. Damnatio Memoriae. [Online] Available at: http://www.livius.org/da-dd/damnatio/damnatio_memoriae.html

Varner, Eric, Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (E.J. Brill, 2004).