In the 7th century, the Neo-Assyrian empire was very expansive reaching from present day Cyprus to Egypt with some of the largest cities at the time. The Neo-Assyrian Empire was in an important alliance with Egypt that helped their influence and expansion. Unfortunately, in the 7th century, there were a series of civil wars that continuously threatened the stability of the empire. Taking advantage up the uprisings, Cyaxares, who was the King of both the Medes and the Persians, made several alliances with other empires including the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Scythians, and the Cimmerians. With this strong alliance, the Babylonians and the Medes were able to overpower the Assyrian-Egyptian alliance in 610 BC when they conquered the city of Harran. After this, the Neo-Assyrian empire faded away into history

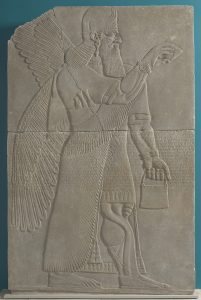

Figure 6. Assyrian Relief from Kalhu, Iraq gifted to Bowdoin College. The Relief depicts the winged spirit known as Apkallu (Bowdoin College Museum of Art).

Ashurnasirpal was king of the Neo-Assyrian empire in the 7th century BC. King Ashurnasirpal was not a god himself, but he was considered to be chosen by the gods. As a result, he was the closest thing to a god and therefore was described to rise to a level of “god likeness”. As king, Ashurnasirpal was responsible for communicating with the gods to ascertain their wishes in order to rule over the humans and maintain the god’s realm properly. These divine entities were represented in the seven demi-gods known as Apkallu. The Apkallu were protective spirits symbolizing wisdom that were depicted as part man and part animal (Figure 6). On reliefs and illustrations, they were frequently pictured with the king or as a blending with the king in order to demonstrate the deities’ approval of the king’s rule. Reliefs were often displayed in the palace in prominent positions for all to see.

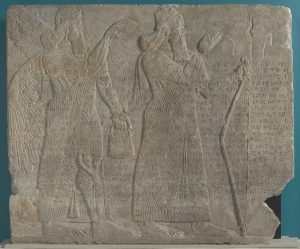

Figure 7. Assyrian Relief from Kalhu, Iraq that was gifted to Bowdoin College. The Relief shows defaced images of King Ashurnasirpal and an Apkallu. The timing of the damage coincides with the invasion of the Medes and Babylonians (Bowdoin College Museum of Art).

In the collection of Assyrian Reliefs given to Bowdoin College, there is one relief that has been disfigured with the Apkallu and King Ashurnasirpal having severed hands and feet with carved out faces (Figure 7). The damage to the relief coincided with the invasion of the Medes and the Babylonians so it is suspected that the invaders of the palace were responsible for this. The mutilation of the king and deity’s image can be seen as a form of Damnatio Memoriae with the invaders attempting to condemn the king’s memory. However, seeing that only the face was carved to be unrecognizable, it is evident that the invaders wished for the audience of this relief to know who had been disfigured. Like other examples of Damnatio Memoriae, the damage done to the king’s image is a complete dishonor and insult to his image. The invaders only defaced one image and not the other reliefs because their point could get across without defacing every image of Ashurnasirpal. Their intention was for history to remember King Ashurnasirpal with this dishonor and as a weak ruler who could not protect his kingdom from invaders.

While this case does not hold the government approval that Damnatio Memoriae had, the defacement of the Assyrian relief remains an example of memory sanction and how the intention of these sanctions were never to erase the memory of a person. The true goal always remained to intertwine the memory of a person with dishonor.

References:

Bedford, Peter R. “The Neo-Assyrian Empire.” The dynamics of ancient empires: state power from Assyria to Byzantium (2009): 30-65.

Thomason, Allison. “The Materiality of Assyrian Sacred Kingship.” Religion Compass 10.6 (2016): 133-148.