As demonstrated above, many Bedford residents are quick to dismiss inclusionary zoning policies due to preconceived notions that simply are not true, or are convenient excuses to keep Bedford the way it currently looks. Before I offer suggestions of my own, I want to show what steps other communities across the country have taken towards housing justice, how it has affected the education in these areas, and what impacts it has had on these communities as a whole. By showing how inclusionary zoning has affected other communities similar to Bedford, I would hope that this would warm people to the idea that it is not only possible in Bedford, but beneficial for the town, too.

The area I will largely focus this section of the case study on is Montgomery County, Maryland. Montgomery County is located right outside of Washington D.C., and is one of the wealthiest counties in America (US Census 2019). Before I dive into the specific inclusionary zoning policies the county has in place, I want to first compare the demographics and income levels of this county to Hillsborough County, the county that includes Bedford and New Hampshire’s two largest cities. Although Montgomery County is over twice as racially diverse as Hillsborough County, it is much wealthier and rent is much more expensive, suggesting that income inequality is far greater. Minority populations represent 40% of the people in Montgomery County, whereas they only make up 17% of the population in Hillsborough County (US Census 2019). That said, the median household income in Hillsborough County is $81,460, compared to Montgomery County’s $108,820 (US Census 2019). In addition, the average monthly rent in Hillsborough County is $1,190, while in Montgomery County, it is $1,768 (US Census 2019). Some may argue that greater inequality and rent prices in Montgomery County make for a greater need for affordable housing there, but the issue is still a significant problem in New Hampshire, and atop the governor’s list of priorities. Just last month, he put together a Council on Housing Stability to address the issue (Sununu 2020). My hope is that by highlighting what Montgomery County, MD has done in terms of inclusionary zoning policies and the effects they have had on education, I can show the people of Bedford how successful these actions can be without negatively impacting the community in the ways people currently think they will.

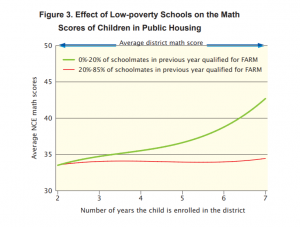

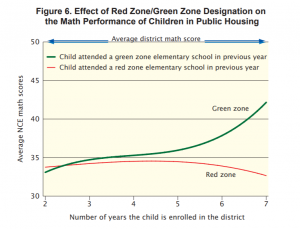

I have found a substantial amount of information on the inclusionary zoning practices of Montgomery County and their impact on education in a study conducted by Heather Schwartz, of The Century Foundation. In her report, “Housing Policy Is School Policy: Economically Integrative Housing Promotes Academic Success in Montgomery County, Maryland,” Schwartz writes extensively on the inclusionary zoning policies of the county and their explicit relation to education. Her findings show that students living in public housing in more affluent areas of the county performed better in reading and math than students in public housing assigned to schools in poorer districts (Schwartz 2010). She continues to explain that the students in low-poverty schools remained in that district for an average of eight years, providing a sense of often-needed stability (Schwartz 2010). Schwartz’s research proves that if more students from low-income families were given the opportunity to attend schools in a district like Bedford, it would go a long way towards closing the achievement gap.

Anyon, too, discusses this issue at length. She highlights the success of Albuquerque, New Mexico’s inclusionary zoning practices on education. The city’s zoning policy requires housing projects to be evenly dispersed throughout the city, thus resulting in a diverse mix of students in schools in middle class neighborhoods (Anyon 2014). Anyon cites a study from the Urban Institute that shows the test scores of children living in public housing increase by 32% when they attend a school over the 80th percentile in test scores as opposed one below the 20th percentile (Anyon 2014). Anyon goes on to mention the Gautreaux Program in Chicago, a very successful housing justice movement from which many lessons can be learned.