The Principles of Organizing and Education as Studied Throughout the Year

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:President_Barack_Obama.jpg

http://images.huffingtonpost.com/2014-12-22-EllaBaker.png

Organizing and Education

There is a symbiotic relationship between educating and community organizing that makes it increasingly difficult to define and distinguish each individual component. A group can educate by organizing, as well as organize to educate. Attempts to separate and define these two activities and their complex relationship can be difficult to understand. I believe the best model to describe this relationship can be drawn from a hierarchy. A group must first realize its power and beliefs, and organize in the process. This group must then educate itself through research and reflection. After this process has been completed, the group may educate others through activism. Finally, the group may implement actual institutional change.

Leadership

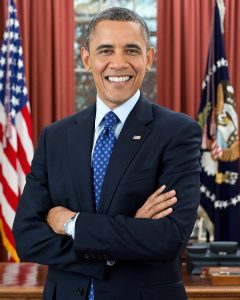

It is important that effective leadership comes from the people themselves rather than solely from a leader. Leaders must have experienced firsthand the causes they wish to advocate for. Two of the community organizers discussed this year that stood out to me were Ella Baker and Barack Obama. One of Baker’s most famous quotes is that “strong people…don’t need strong leaders” (Payne, 893). Maybe people don’t need leaders, but that isn’t to say they aren’t a useful asset for oppressed people. Figures like Barack Obama, who embraced some of Baker’s principles, while gaining recognition from a larger public, were ultimately more influential and successful. It is acceptable to allow a specific leader to stand out in a movement, and for that leader to seek large masses of followers for the movement, because that is the way that power is built.

Obama agreed that effective leadership would come from the people themselves rather than solely from a leader. “A viable organization can only be achieved if a broadly based indigenous leadership–and not one or two charismatic leaders–can knit together the diverse interests of their local institutions” (Obama, 29). Obama also believed that masses were important for a movement to have power. While Baker was a proponent of looking at all the individual groups within a public, Obama believed that many interest groups must band together to create a powerful base. “This means bringing together churches, block clubs, parent groups and any other institutions in a given community to pay dues, hire organizers, conduct research … once such a vehicle is formed, it holds the power to make politicians, agencies, and corporations more responsive to community needs” (Obama, 29). Baker’s approach was more about mobilizing each of those forces individually, and Obama expanded that idea to include a mass of forces.

Instead of completely opposing a charismatic leader, maybe the public should be aware of how it can use media to undo a leader if necessary. Understanding this could allow people to exploit their leader, rather than be exploited by a leader. The public can create a leader, instead of letting someone rise up and dominate a cause. If the public knows how to use media effectively, it can make a leader essentially an extension of the public. It is possible for a leader to be a figurehead for a movement and assist the movement in gaining support and membership without overshadowing the power of the public itself.