Trouble or Trauma? Support & Resilience in Urban Schools & Communities

These articles discus how schools, communities, and institutions respond to “disruptive” students with punitive punishments who need support and medical assistance (Carter, Calvo, Abraham, & Ukeje 8). Sad, Not Bad Katharine Carter provides innovative approaches to student discipline, which recognize and react to traumatized students more effectively. In Trauma-Informed & Resilient Communities: A Primer for Public Health Practitioners, Calvo et. all “trauma-informed” policies and practices provide solutions to challenges posed in Sad, Not Bad. The articles suggest schools, communities, and state institutions lack an understanding of trauma and its impact, which has detrimental effects on low-income youth.

Trauma

Carter defines “trauma” as a “deeply disturbing experience or response to a terrible event” (Carter). More specifically, Calvo et. al borrow a definition from The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA):

“Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual wellbeing” (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 4).

Carter and Calvo et. al break down the phenomenon of trauma based research of the health risks of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The study identified three types of ACEs:

- Abuse: physical, emotional, or sexual

- Neglect: physical or emotional

- Household Dysfunction: mental illness, abusive or abused parent, divorce, incarcerated relative, or substance abuse

Health Implications of Trauma

Trauma negatively affects the undeveloped neural pathways in a young person’s brain, impacting their “responses to danger, impulse control, and memory” (Carter). This can put children in a “state of hyper-arousal,” which can lead to overreactions. Internal reactions to trauma include: loss of motivation, reduced class participation, and depression and their external reactions include: “outbursts, violence, and defiance” (Carter).

The effects of trauma prevail into adulthood. Studies show links between ACEs and behavior, physical, and mental health deficiencies. Further, the more ACEs one experiences, the greater their risks are of disease, substance abuse, and overall poorer health (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 3).

Trauma-Induced Health risks include:

- Diabetes

- Depression

- Suicide

- STDs

- Heart disease

- Cancer

- Stroke

- COPD

Trauma in Low Income Urban Communities

Communities of color are susceptible to ACES due to the combined effects of “community violence, poverty, incarceration and institutional and overt racism” (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 6). Urban poverty is itself “independently associated” with greater exposure to traumatic events because these communities experience the most traumatic stress and have the least resources combat the effects.

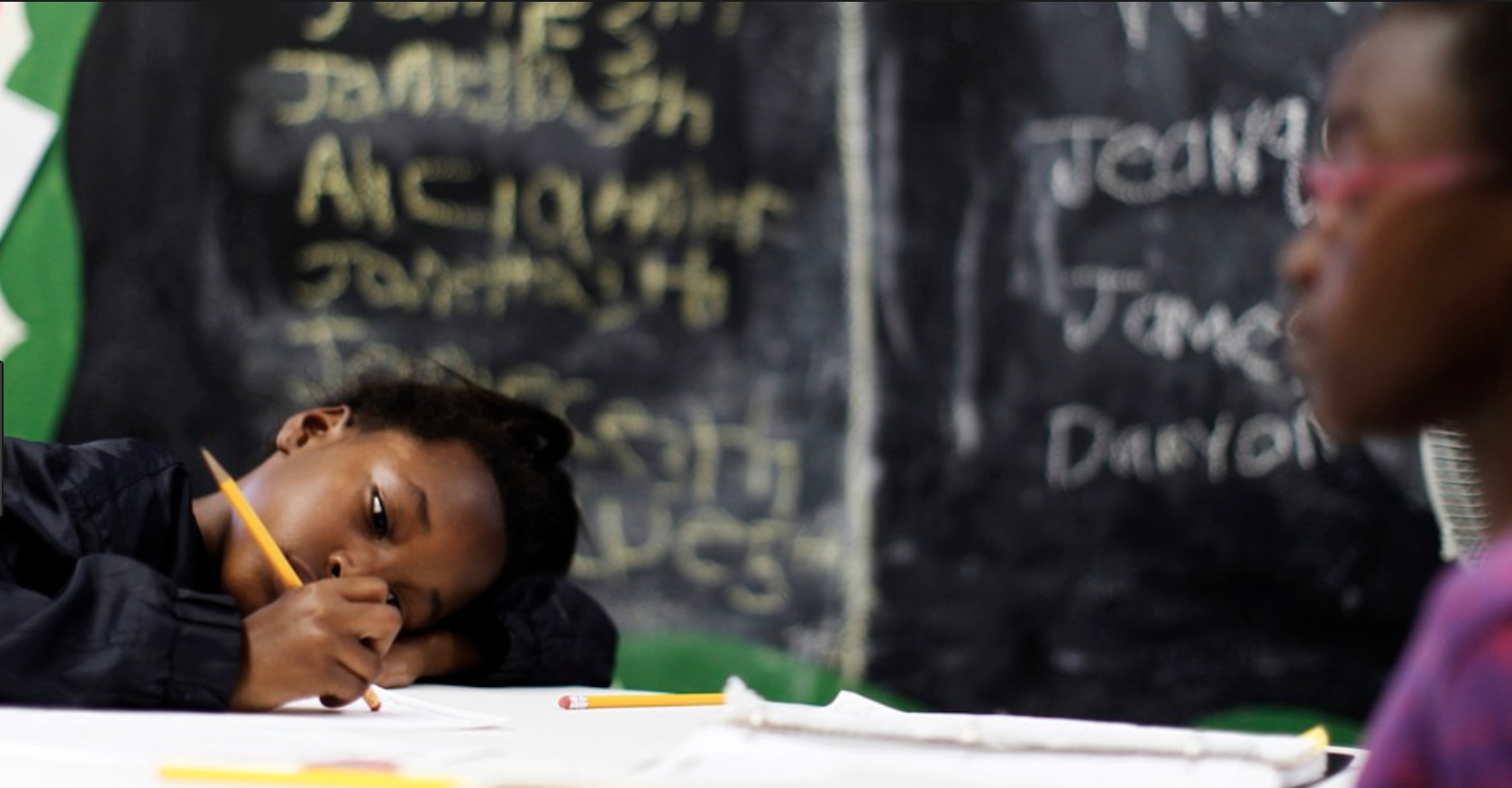

Recognizing Trauma in Urban Schools

Trauma is prompted by individual, familial, community, and environmental factors, as well as personality, past traumatic experiences, family history, coping skills, and cultural beliefs (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 5). These factors also shape a person’s capacity to recognize the effects of trauma by distorting their perceptions of “normal” life experiences (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham6). One’s perception of “normalcy” effects how they expressively respond to and understand trauma. This also makes identifying traumatized individuals challenging since pain may be disguised (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 6).

In poor urban schools, punitive and exclusionary disciplinary policies magnify the problem by training teachers to interpret disruptive students as “trouble-makers” who deserve strict punishment. The focus on punishment authorizes teachers to read hostile behavior as a choice that derives from anger rather than pain. Carter suggests schools adapt “trauma-informed” policies and procedures, which educate teachers and administrators about trauma so they can more appropriately respond and support traumatized students.

A Trauma-Informed Approach

Calvo, Ukeje, Abraham, and Carter promote “trauma-informed” practices in schools, organizations, and communities. A “trauma-informed” system is defined as one that “recognizes and responds to the effects of trauma – and which avoid re-traumatization” (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 8).

A “trauma-informed” approach (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 9):

- Creates a psychologically and physically safe environment.

- Decisions and actions plans made with the students and community

- “Peer Support” Individuals who’ve experienced trauma are included in decision-making process and serve as mentors

- Cultivates strong relationships between all involved entities

- Recognizes and builds upon individuals’ strengths and experiences.

- Fosters belief in resilience and the ability to heal and recover from trauma.

- Empowers traumatize youth

- Organization “moves past cultural stereotypes and biases” by incorporating policies respond to the “racial, ethnic and cultural needs of the individuals served.”

- Recognizes and addresses “historical trauma.”

- Fosters resilience: “the capacity to cope with stress, overcome adversity, and thrive despite, and perhaps even because of, challenges in life.” (Calvo, Ukeje, & Abraham 11)

Trouble or Trauma? It matters.

Youth from poor urban communities experience trauma at higher rates than any other demographic of students because they are disproportionately exposed to violence, poverty, and punitive systems of control (Carter, Calvo, Abraham & Ukeje 6). Under these conditions, students are labeled “trouble-makers” and punished for behaviors that aren’t actually threatening (Carter). As a result, trauma-induced behaviors are misinterpreted, resulting in punishments that suspend, expel, and isolate students in need of attention and support.

Students who do not receive the medical and community support are at risk for negative health effects, reduced academic opportunities, and the school-to-prison pipeline. As such, these articles insist schools implement “trauma-informed” practices that foster more awareness of trauma so that schools and communities can see that being a “trouble-maker” is not a choice.

Calvo, Michael, Ukeje, Chideraa, and Abraham, Rebecca. (June 2016). “Trauma-Informed & Resilient Communities: A Primer for Public Health Practioners” Advancing Prevention Project. http://www.advancingpreventionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Trauma-Primer-Final.pdf

Carter, Katharine. (June 2017). “Database: Sad, Not Bad.” National School Boards Association. https://www.nsba.org/newsroom/american-school-board-journal/asbj-june-2017/database-sad-not-bad.