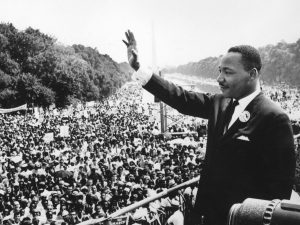

Defining an organization as grassroots can be challenging. What comes to mind when you think of a grassroots organization? Is it a group of people marching with signs and chanting catchy slogans? A charismatic leader making an inspiring (or over-the-top) speech to a crowd of hundreds? How about a sit-in or a walk-out? While these are all significant parts of organizing, my research on communities of color in education has shown me what the full spectrum of grassroots organizing looks like.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/08/protests-vigils-decry-white-supremacism-170813232011259.html

https://www.npr.org/2010/01/18/122701268/

Archetypal Grassroots Organizing

I have learned that the work of grassroots organizers in education is far less glamorous than the this archetype. Instead, it often looks like a group of teachers, parents, students, and other community members simply talking to each other.

- Organizers take up seemingly mundane and menial roles that are just as important as making televised speeches or holding a rally. Community organizers:

-

- Expand their social networks and strengthen the connections within the community through simply engaging with each other. When oppressed people share their experiences–their successes, failures, dreams, and fears–they participate in what Paulo Freire calls “liberation education,” and learn how they are connected in a racist system (Martinson & Su 2012, p. 66). With this comes communal resilience.

- Learn about and actively become part of school and local politics. They sit in on school board meetings, read about policy, and even run for local positions. They get involved in education: Parents may help their children do their homework, volunteer in the classroom, or join the PTA.

- Build Coalitions: they connect to other groups organizing around similar or divergent reasons, identifying how systems of oppression link different communities and interest-groups. They may build connections with local institutions (schools, houses of worship, colleges, local governments) to strengthen their impact.

- Of course, on top of the nitty-gritty, grassroots organizers will still hold rallies and make publicized speeches. However, this project has taught me to look into the small-scale work of community organizers.

What grassroots community organizing often actually looks like (http://www.apano.org/programs/community-organizing/)

My research has taught me carefully to consider if an organization actually fits into the category of “grassroots,” and to look at what type of impact a group has.

- Some groups that are positively affecting change aren’t necessarily grassroots. For example, one group I researched is Encuentros Teachers Academy, an annual program hosted by CSU San Marcos to inspire and to assist high school-aged Latino boys in embarking on the path to becoming teachers. While the organization succeeds in putting these young men of color on the track to becoming educators (93% of their participants go on to earn college degrees), it was unclear to me whether or not the organization was grassroots or simply an education non-profit (Warth 2017). On one hand, the institute’s leadership and membership is made up of teachers and school faculty at the high schools that participate in the program; on the other hand, it was founded by a professor at a university with university funding (Warth 2017). While I believe their work should be celebrated as inciting social change, it ultimately does not fit into the category of a grassroots educational organization.

https://nycmenteach.org/

Through my research, I learned about organizations that compete with grassroots groups to “solve” the systemic injustices in urban education.

- Neoliberalism–the idea that privatization, competition, and choice yield excellence–often infiltrates the realm of urban education when wealthy philanthropists pour money into what they see as “solutions” to urban issues that do not target systemic injustices (Lahann 2011).

- For example, I researched The Fellowship: Black Male Educators for Social Justice. This Philadelphia non-profit has helps men of color become teachers–something that seems good on the surface. However, at the same time, it supports charter schools, which take power away from communities of color (to read more about the problems with charter schools, click here). This is unsurprising, considering that the organization receives its funding from the philanthropic wings of large corporations.

- Neoliberal reform perpetuates the myths of the economic status quo:

- that those with the most money rightfully earned that money

- that those with money must be smart and therefore have the solutions to society’s problems

- that those with money should keep making money because they are so generous to those without money

- Astroturf: Then there are organizations that pose as grassroots (Barkan 2012). These lobbying groups often take money from well-funded interest groups, and chanel their influence to shape the narrative on social problems and their solutions–ultimately preventing the true grassroots from having their voices heard (Barkan 2012). While I couldn’t find evidence of an astroturf organization that speaks specifically on the issue of a lack of teachers of color, many exist in the realm of education, and threaten to shape the narrative on systemic injustices. In doing my research, I had to keep my eyes peeled for organizations like the Alliance for Educational Excellence that promote neoliberal ideas like standardized evaluation of teachers–which hurt teachers of color.

True grassroots organizations have a lot to go up against; not only must they work to fix the problems their communities face, but they must also fight those who implement “solutions” to these problems that only work to perpetuate systemic injustice. We must learn about and honor the work of grassroots organizers, who often do the nitty-gritty work of social change in the shadows of flashy neoliberal reform.

https://www.therenewalproject.com/the-power-of-role-models-how-male-teachers-of-color-can-make-a-difference-in-young-mens-lives/

Works Cited

Barkan, J. (2012). Hired Guns on Astroturf: How to Buy and Sell School Reform. Dissent Magazine, (Spring 2012). Retrieved from https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/hired-guns-on-astroturfhow-to-buy-and-sell-school-reform

Lahann, R., & Reagan, E. (2011). Teach for America and the Politics of Progressive Neoliberalism. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(1), 7-27. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23479639

Martinson, M., & Su, C. (2012). Contrasting Organizing Approaches: The ‘Alinsky Tradition’ and Freirian Organizing Approaches. In M. Minkler, Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare (1st ed.). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Warth, G. (2017). Why young Latino men don’t think of becoming teachers. The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/education/sd-me-latino-teachers-20170713-story.html