We often hear of experiences that are “better than sex,” e.g. chocolate or jumping out of a plane. But what’s weirder than sex? What human (or beyond human) experiences make us question how pleasure, desire, and fantasy structure our social world. Queer theory has often turned to study sex as an important cultural practice where people elaborate both their desires and their sense of self. Sex is an important site to study because of the many incoherent narratives that people construct around it. By looking at why each one of us has the pleasures, desires, and fantasies that we do, free of a moral structure around those dispositions, we better understand the human condition. Sex can be exciting, scary, affirming, harmful, unexpected or monotonous. But it is above all else weird—a space where alternative ways of encountering our own bodies and the world can be explored (or avoided). Yet sex is not the only site to explore the weirdness of human experience. We use the language of pleasure, desire, and fantasy to narrate our relationships to food, consumerism, “the good life,” activist politics, and fan fiction. What do these experiences tell us about the ambivalent, overwhelming, or incoherent character around desire (+pleasure + fantasy)?

Author Archives: Jay Sosa

Gender…Alone Together

Do we enact gender alone or together? Gender in one aspect, highly individual. Feminist and trans* activism has made respecting the autonomy of one’s gender a key political act. Under this paradigm, we each present gender based on how we intuitively feel about ourselves and express those feelings outward through clothing, gesture, voice, etc. But gender is also incredibly social. We don’t invent gender spontaneously, but rather rehash it through codes that are given to us. Our set of gender intelligibility is limited by the citations of previous gender norms and how we interpret them. To what extent, then, is gender something we have, something we are, or something we do? How do we contend with the “forcible citation of the norm” (Butler 1993), as something that both breaks us and makes us?

Can there be norms in utopia?

Are there social norms in a queer utopia? Can or should there be? Normativity (the social imposition to fit the norm) is often conceptualized as the basis of much anti-LGBTQIA+ existence. Yet norms are often necessary for some of the very liberation goals of LGBTQIA+ people. The turn to utopian thought as a horizon of what queer life could be raises the question of how such utopian social relations might be cultivated or sustained without norms (or laws, or some mode of “discipline”). Using the spatializing language of orientation, we might also question how norms (and their temporal existence in the ‘now’ and spatial existence in the ‘middle’) might be compatible or incompatible with utopic queerness as a horizon (with its orientation towards the ‘not yet’ and the ‘far off’). Further, queer theory treats norms as an object of critique and utopia as an object for imagination. Is the very desire to combine critique and imagination itself utopic?

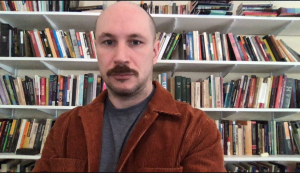

I fretted as I tried to decide the background for a Zoom panel where I would be the center of attention for a three hour presentation. Usually, I consider myself a zoom naturalist (or maybe a minimalist?), presenting as neutral a background to my Zoom room as I can. Occasionally, I opt for to position myself in front of a bookcase, a prop that I had learned during “Skype interviews” on the academic job market and that now corresponds to the professor drag persona I try to play. For zoom-based classes I taught on Brazil, I occasionally experimented with digital backdrops where I appeared amidst various Brazilian cities.

Of course, I am not alone. Over the past two years of the COVID pandemic, self-presentation on zoom has become an almost daily professional and personal concern of the white-collar class, as others see us (and we see ourselves) on Zoom. This doubleness of self-presentation—seeing ourselves in the same window as others see us, has created a weird sense of self online. Zoom users have reported not liking seeing themselves online and zoom dysmorphia. Zoom backgrounds are, undoubtedly part of this new presentational style, as online guides help users find the background that is right for them. In another sense, Zoom has redefined what is in our background—what we can hide or display about our everyday domesticity and reproductive labor.

Can the transformed self-presentations brought on by the Zoom-from-home work era be said to be queer in some way? How might Zoom have “re-oriented” our sense of self as well as self presentation? In her “Towards a Queer Phenomenology,” Sara Ahmed (2006) asks how the study of orientation can expand the theoretical purchase of queer studies. Ahmed focuses on the who and what towards which we are oriented as the basis to question certain normative trajectories of heterosexual desire, procreation, and relationships. To ground phenomenological study, Ahmed draws on philosopher Edmund Husserl’s description of sitting at a table as an orienting experience. She draws attention to how Husserl identifies the background as that to which he doesn’t face. It is by turning his back that a background is created. In Husserl’s case, creating a background means ignoring the reproductive labor his wife does in order to allow the time and space for Husserl’s scholarly writing.

Of course, the contemporary mode of intellectual labor production around the digital meeting upends this analog relation between foreground and background. Not only do we see (and begin to curate) that which we have turned our backs towards, others see past our careful professional presentations and into our domestic space. In the first few months of COVID, this window into reproductive labor was more acute, as the unsophisticated techniques of self-presentation revealed the obscene luxury of celebrity homes or the chaos of middle class parents trying to exclude the non-professional sensoria. But even now that we have found ways to hide or alter our backgrounds, can we ever say again that we ignore them (or that they are backgrounds as such)? A queer look at Zoom backgrounds might reveal how we are now exposed (and performing) in new ways.