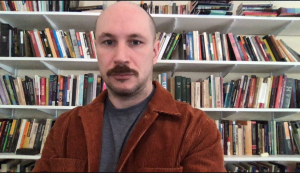

Nolan Gerard Funk as Conrad Birdie in Roundabout Theater’s 2009 production. Source: New York Times

“For he’s a fine, upstanding, patriotic, healthy, normal American boy.”

This is a glowing description given to Conrad Birdie, the title character in the classic American 1960s musical Bye-Bye Birdie. In the song “Normal American Boy,” Birdie’s staff and fangirls extoll his virtues for a crowd of tabloid reporters who are eager to learn about the teen idol’s response to being drafted in the army. The song does the work of promoting the straight value of normativity, alongside glorifying the military and patriotism. However, the conceit of the song is that Birdie is actually none of these things, and his staff are telling these outrageous lies in an effort to maintain Birdie’s reputation while they try to preserve their jobs and save their production company from bankruptcy. The song successfully promotes normativity while also teaching us that anyone who is deliberately calling themselves normal is some kind of scammer or con artist.

Normativity is an American value, but it only works when we don’t talk about it. If a person who is truly normal exists, we have certainly never heard of them, and they will never identify themselves, because in the moment of identifying someone as normal, they lose their normal status. Normativity takes on a shadowy role, much like that frustrating elementary school game, creatively named “the game,” where as soon as you remember that you’re playing, you’ve lost.

Like normativity, queerness is another mythological idea that is impossible to imagine or invoke in our present time. But that hasn’t stopped corporations and institutions from pulling their own con – trying to steal the word queer and co-opt its meaning, taking it away from the future utopia by assuring us that it can be folded into straight time. When a corporation assures you that they are queer, look for the publicists behind the curtain, just like the ones in Bye-Bye Birdie, who are only trying to make money for the boss and save their own skins.

Multnomah County Sheriff car decorated for pride month. Source: katu.com