Overview

The Arctic is not a solely definable place—especially when you consider the vast array of people and cultures that call the Arctic home. The issues that face the Inuit people in Canada are different than those that the Sami in Scandinavia are facing, and thus we want to acknowledge outright that the issues, policy proposals, and background we will be discussing on this website is limited in focus. The majority of this research focuses on the indigenous peoples of Canada and their experiences and hardships with infrastructure, particularly healthcare infrastructure.

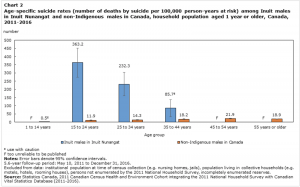

The health of indigenous Arctic communities is a topic that has been vastly researched, and for good reason: indigenous communities are suffering. In Northern Canada alone, the infant mortality rate is four times greater than Canada’s national rate. Additionally, the suicide rate for Inuit populations in Canada is about 11 times higher than the international average.This is a crisis in every sense of the word.

When considering these facts, a large theme emerges: the lack of healthcare infrastructure in Canadian Inuit communities is causing significant harm. For many of these communities, the nearest hospital is hours away or is only accessible by air, meaning individuals who face emergency health situations may not get the proper care they need in the time they need. This also causes problems for pregnant Inuit people, who, should they want to give birth in a hospital, have to fly hundreds of miles away from their home in order to do so. Finally, the suicide rates for Canadian Inuit youth beg a change, and in communities where youth centers have been built, the suicide rate has dropped off significantly.

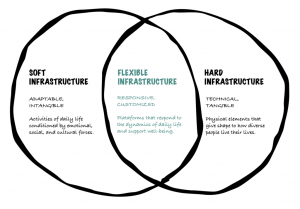

The problems facing these communities extend beyond inadequate hard infrastructure; soft infrastructure is necessary, too. Doctors in these communities are few and far between, as is training for new mothers on how to prevent infant mortality. Further, suicide prevention training is a necessary yet hard service to come by, a service that could save hundreds of lives. In short, the lack of physical infrastructure is not the only barrier to healthcare, the lack of soft infrastructure poses a real problem, too.

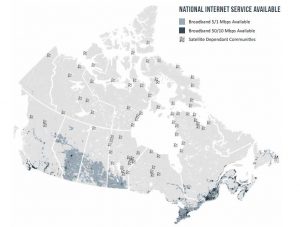

In thinking about all of this, it’s also important to consider the role of internet access in aiding these services. Increased internet access provides a strong, physical platform to build upon. Hard infrastructure like telecommunications and electric grids allows for future construction of clinics, education programs, and telehealth opportunities while also offering a pathway for Inuit communities to engage with their culture and traditions alongside the rest of the world. There is no world in which healthcare infrastructure in the Canadian Arctic can be improved without also improving internet access.

So, how do we fix this? Who pays for these services and buildings? How do we collaborate with indigenous voices on these projects? Our policy proposals go in-depth on these questions. Explore our policy proposals here. You can navigate between subsections on certain issues such as infant mortality, suicide, doctors and hospitals, and internet access.

But what about indigenous understandings and approaches to health? How does that intersect?

All of this being said, we want to acknowledge that how we understand “healthiness” is a Western construction. Traditional knowledge has kept indigenous communities alive and healthy for centuries, and we are under no pretenses that suddenly adhering to Western notions of health will suddenly improve indigenous communities’ healthiness. Rather, Western understandings of medicine and infrastructure are a supplement to traditional knowledge, and we want to be sure that our research acknowledges this.

Can this research be applied to other regions?

There is no “one size fits all” to health infrastructure. As we addressed earlier, much of our research focuses on Canadian Inuit communities. Therefore, applying the research we’ve done to other Arctic communities should be done in a manner that considers the nuances and needs of each community. Action plans must be crafted on a case-by-case basis, ensuring that each voice is heard and that special attention is given to Indigenous issues caused by colonization.