Sea Ice in Nunavut, Canada (Fiona Paton, 2018, https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/how-i-wrote-symphony-about-changing-canadian-arctic).

Background:

Although climate change is the hot button issue these days, global pollutants, such as Mercury—a human neurotoxin, which is symbolized with an “Hg”—POPs, Black Carbon, and Microplastics pose more serious and immediate health concerns to indigenous peoples and animals living throughout the Arctic

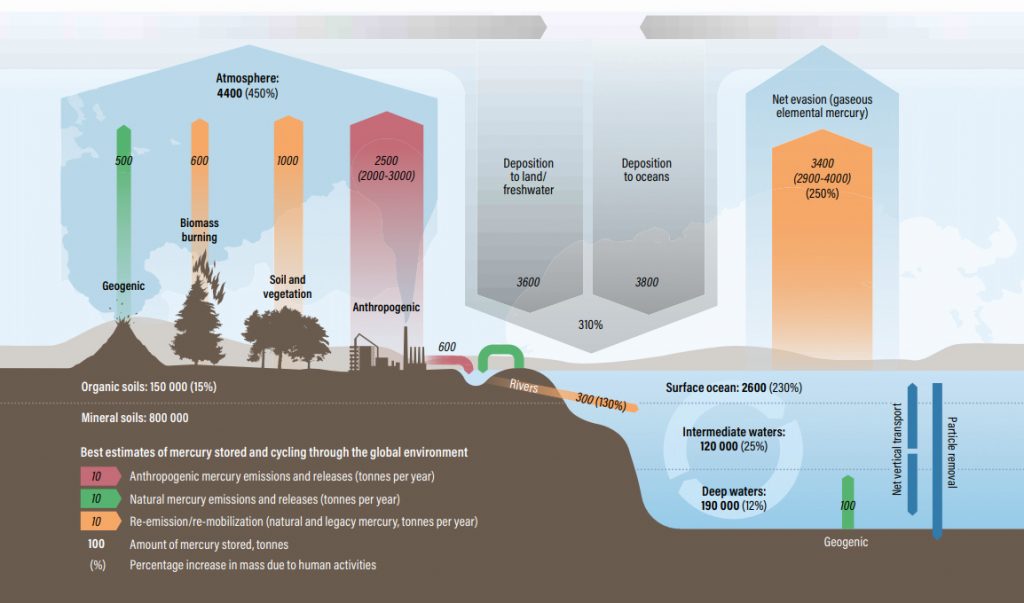

Despite limited Mercury emissions in the Arctic, atmospheric transportation and river discharge brings Mercury emitted from around the world by anthropogenic (human) sources to the Arctic, where it accumulates or, as scientists call it, sinks.

UN Environment 2019

As a result, dangerous levels of Mercury have been recorded in the Arctic ecosystem and environment which have caused adverse health effects on the most vulnerable populations: newborns and pregnant mothers. Mercury transport and its effects have been studied in depth in the Canadian Arctic.

However, through the Minamata Convention, the world has a blueprint for a strong effort to decrease the amount of Mercury circulating in the environment, yet the convention is relatively new, its impacts and effectiveness are unclear, and while it is legally binding, it does not force remediation.

Yet, sadly, like other pollutants in the Arctic, remediation is not a likely solution for Mercury with our current technology despite being possible elsewhere in the world, and because of the way Mercury enters the human body, the effects of decreasing emissions will not quickly and immediately solve the problem.

Below, you’ll find a presentation on Mercury within the Canadian Arctic. In it, you will find three sections:

- A scientific study of how Mercury speciates and moves throughout the world, the Arctic environment, and the Arctic ecosystem with a specific focus on how it enters humans through a case study of the Canadian Arctic

- A discussion of the policy solutions with specific emphasis on the Minamata Convention, its effectiveness and its shortcomings

- Two policy recommendations, one at the global level and one at the local level

Presentation:

[ensemblevideo version=”5.6.0″ content_type=”video” id=”58911af9-fee0-4440-9f1c-2f18705cc494″ width=”848″ height=”480″ displaytitle=”true” autoplay=”false” showcaptions=”false” hidecontrols=”true” displaysharing=”false” displaycaptionsearch=”true” displayattachments=”true” audiopreviewimage=”true” isaudio=”false” displaylinks=”true” displaymetadata=”false” displaydateproduced=”true” displayembedcode=”false” displaydownloadicon=”false” displayviewersreport=”false” embedasthumbnail=”false” displayaxdxs=”false” embedtype=”responsive” forceembedtype=”false” name=”Mercury in the Canadian Arctic: Sources and Solutions”]

Policy Suggestions:

In order to solve Mercury pollution in the Arctic, there needs to be a two front approach: global and local. The solution to mercury pollution in the Arctic cannot be solved on just the global or just the local level because a global solution will decrease emission but not solve immediate health issues of local indigenous populations, and a local solution would not be a long-term fix.

Global:

We must continue the global effort to decrease anthropogenic sources of mercury by involving scientists and continuing to have retrospective analyses of the state of Mercury production, transportation, and speciation. Environmental treaties can help expand research opportunities which in turn can support implementation of those treaties and feed into policy-making and management (Selin et al. 2018, 210), so we must continue to use and hold the Minamata Convention as a central, especially the section about monitoring (use bioindicators as they are the slowest to change!) as well as study atmospheric transport of mercury and reemergence of mercury from sea ice (that’s a gap in a lot of this research). This global effort could and should also monitor the other pollutants mentioned on this site: POPs, Microplastics, and Black Carbon.

Local:

The Canadian federal government must fund local studies and organizations that can make recommendations about the possibility of substituting traditional foods with western foods. There needs to be a focus on studying adverse health effects of long-term exposure to mercury in adults, especially in communities with elevated mercury levels (Pirkle, Muckle and Lemire 2016, 1021), and further research into food security, malnutrition (including obesity), micronutrient deficiencies and mercury toxicity needs to be funded (Pirkle, Muckle and Lemire 2016, 1021). Finally, at the local level, Inuit leaders and community members must be involved in conversations to educate them and their communities about the benefits and risks behind a possible transition to western/imported food.