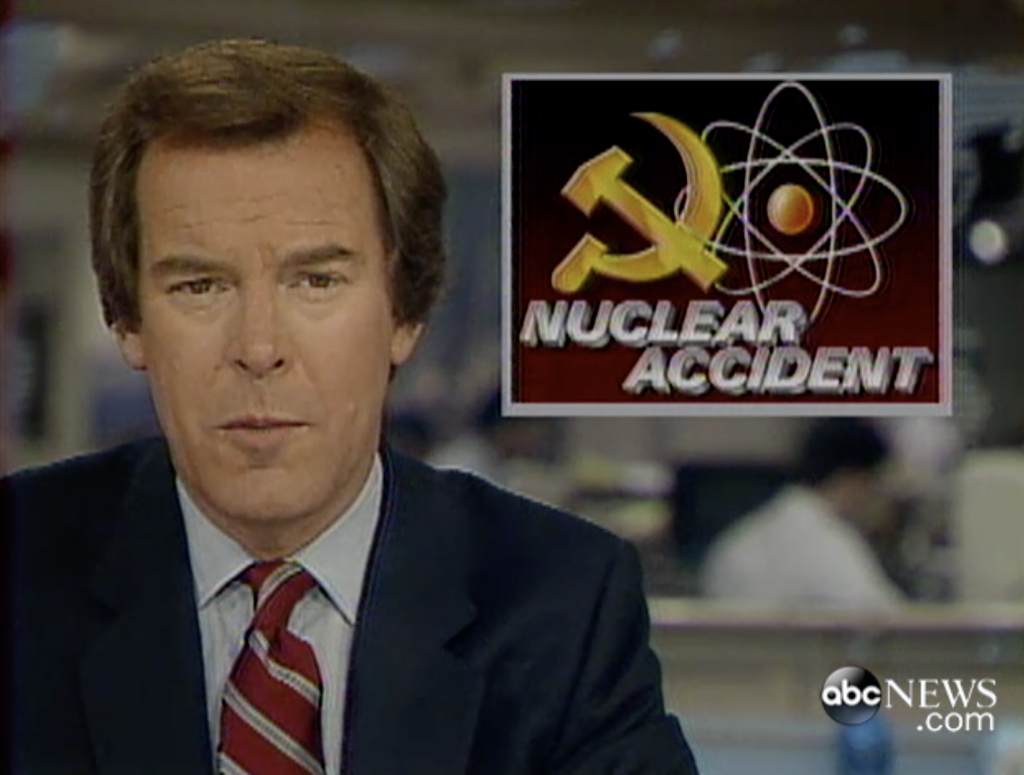

CLICK the image or the link below to watch a short abcNEWS segment from April 28, 1986 about the Chernobyl accident.

CLICK HERE: April 28, 1986 Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster abcNEWS clip

Excerpt from the International Herald Tribune May 2, 1986 (Schmemann and New York Times Service 1986). Click image for link to full article (on Bowdoin network).

Outside of the Soviet Union (USSR), the world was unaware of the Chernobyl accident until April 28, 1986, two days after the meltdown of Reactor No. 4. At the Forsmark nuclear reactor in eastern Sweden, a worker arrived for his shift and set off an alarm indicating abnormally high radiation levels. Subsequent analysis revealed that the “radioactive dust” on the Forsmark reactor worker’s shoes was not due to a malfunction at Forsmark—or any other nuclear reactor in Scandinavia. Instead, the radioactive materials had come from 900 miles away in Ukraine (Browne 1986).

According to Malcolm Browne, a journalist for The New York Times, “Sweden was ideally situated to peek under” Moscow’s “veil of secrecy” surrounding the Chernobyl accident due its close proximity to the USSR. Swedish nuclear physicists utilized European nuclear radiation data to trace the source of radiation to the Chernobyl plant (Browne 1986). But, only after Sweden “spent a full day demanding information” from the USSR, did Moscow issue a 44 word statement regarding the Chernobyl accident (Schmemann and New York Times Service 1986). The Western world was largely dissatisfied by the lack of detail in Moscow’s statement. On May 2, 1986, one journalist demanded “the most basic facts: What happened? When? How much radioactivity has escaped and over how broad an area? How many people have been exposed? Is the leak continuing?” (Schmemann and New York Times Service 1986).

The English-speaking international press was particularly focused on the lack of information surrounding Chernobyl. Although Polish scientists were aware of abnormally high radiation levels on April 27, 1986, before Sweden sounded international alarms, Polish scientists later shared that they were fearful of sparking mass hysteria (Kaufman and New York Times 1986). Similarly, Finland—another country that had measured abnormally high radiation levels—refrained from condemning the USSR’s failure to release detailed information. As a result, one Finnish citizen, Jorma K. Miettinen a Helsinki University professor, lamented: “‘Americans think Finland is subservient to the Soviet Union’” (Kaufman and New York Times 1986). Some European countries attempted to take neutral stances on the Chernobyl accident, but these neutral stances sparked even more anxiety in light of a major nuclear accident and the Cold War.

Quote from Mieczyslaw Sowinski, head of the Polish atomic energy agency, explaining why Poland refrained from mentioning high radiation levels measured on April 27, 1986 (Kaufman and New York Times 1986).

Quote from Jorma K. Miettinen, a Finnish Helsinki University professor, lamenting Finland’s failure to condemn the USSR (Kaufman and New York Times 1986).

The Cold War was also a significant part of the news cycle in both the USA and the USSR. On April 29, 1986, the International Herald Tribune ran a front-page headline “Nuclear Accident At Soviet Plant Causes Injuries.” Much of the article described what was known about the Chernobyl accident, but the concluding paragraph shifts the narrative to the Three Mile Island accident, termed “The worst commercial nuclear accident in the United States” (Compiled by Our Staff from Dispatches 1986). Additionally, reports from the USSR suggested that Soviet government officials “issued assurances that nothing all that terrible had happened,” and the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) issued “a far longer dispatch detailing the Three Mile Island accident” (Schmemann and New York Times Service 1986). After the Chernobyl accident, both the USA and the USSR had major incidents involving civilian nuclear power. Both Cold War superpowers attempted to draw emphasis away from their own technological failings by criticizing their counterpart’s nuclear programs.

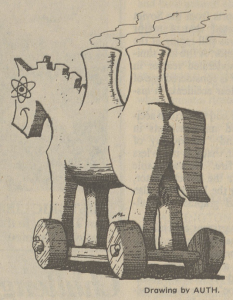

“The Nuclear Trojan Horse” drawing by Arthur H. Purcell calling for increased, international safety measures to the nuclear power industry (Purcell 1986).

Moreover, the Chernobyl accident reignited calls, for increased safety regulations on nuclear energy, that received significant attention after the Three Mile Island accident. Arthur Purcell, director of the Washington Resource Policy Institute, emphasized Chernobyl’s “damning contribution to the international nuclear policy debate;” the Chernobyl accident demonstrated that nuclear power is “inherently unsafe” (Purcell 1986). In the Cold War era, as the world waited anxiously for a potential nuclear war, the Chernobyl disaster confirmed for many that the nuclear energy industry posed significant threats along with nuclear weapons.

Ultimately, news stories published in April-May 1986 illustrate global uncertainty and fear surrounding the Chernobyl accident. After the accident occurred, the USSR was reluctant to share relevant details even though the international press and many countries demanded information. Adding to these anxieties—stemming from the lack of information about the nuclear disaster—was the backdrop of the Cold War and fear of a nuclear war. Many news sources pointed to the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in the USA, and both the USA and the USSR aimed to de-emphasize their nuclear technology failings. Yet in response to these accidents more calls for stringent international nuclear safety measures entered public narratives of nuclear power. Chernobyl may have confirmed that the USSR’s nuclear technology was with many faults. But the media refused to forget similar failings in the USA. Therefore, the West’s understanding of Chernobyl was largely framed by the Cold War and technological failings on both sides.