The AIDS crisis is an infamous event in American History; nearly 700 thousand Americans have died of AIDS-related causes since the start of the epidemic, and around 1.2 million people living in the United States are infected with the disease today (CDC, “HIV Basic Statistics”). The event has been portrayed in numerous culturally significant works spanning the genres of literature, film, visual art and theater. It sparked massive political and cultural controversy, expressed both through loud and eye-grabbing demonstrations and equally impactful silence.

(A scene from Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, a play addressing the AIDS Crisis)

The earliest case of AIDS verified through a blood sample was in 1959 in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, though a modern “‘family-tree’ ancestry of HIV transmission” suggests the first infection occurred circa 1920, as a mutation from a Simian Immunodeficiency Disease commonly found in chimpanzees (Avert, “HIV Origins”). The disease spread from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to Haiti in the early 1960s (Ibid).

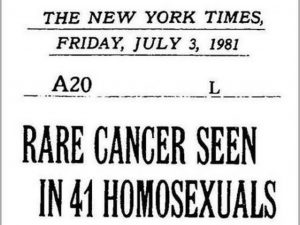

The first cases of AIDS reported in the United States are sourced from the CDC’s 1981 “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,” in which it was reported that “five young, white, previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles” developed a rare type of pneumonia from what we know was a symptom AIDS; the same day this report was published, a prominent New York-based dermatologist reported an aggressive and rare cancer associated with weakened immune systems in both New York and California (HIV.gov, “Basics Overview”). All the affected individuals died. By the end of the year, the number of cases (and deaths) had entered the hundreds, with 94% of victims identifiable as gay or bisexual (Ibid.).

The prevalence of the disease in the MSM (men who have sex with men) community within the United States meant AIDS was a stigmatized illness from its conception. Initially, the dominant medical discourse surrounding the illness was that the disease only existed within gay and bisexual communities; while New York doctor Arye Rubinstein recognized the disease in five infants whose mothers were involved in sex work in 1981, his “diagnoses are dismissed by his colleagues”(Ibid.). The notion that the disease only affected gay men lead to both official and colloquial use of terms such as “gay plague,” “gay cancer,” and “gay-related immuno-deficiency” (GRID) (Avert, “HIV Overview”).

(Source: https://www.tenement.org/hiv-aids-rising-panic-and-community-activism/)

In September of 1982 the CDC first used the term AIDS to describe the disease, which by this time had infected thousands within the United States, with cases emerging globally as well (Ibid.). (AIDS is a descriptor of the numerous ways the body is impacted by the reduced immune capacity caused by the virus now known as HIV; this virus was not named HIV until 1986) (Ibid.). This official nomenclature did little to mitigate the growing stigmatization within the AIDS discourse. The CDC identified “homosexuals, people who inject drugs, hemophiliacs and people who have recently been to Haiti” as the four at-risk groups for AIDS; this announcement lead to the disparaging colloquial practice of labeling AIDS victims as the “4-H Club” — homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin addicts, and Haitians (Avert, “HIV Origin”).

While medical discourse was far from progressive in the early days of the AIDS crisis in the United States, medical institutions responded to AIDS as early as 1981. That year, the National Cancer Institute and CDC cosponsored the first conference to discuss the new epidemic and possible treatments. Likewise, a clinic in San Francisco founded by Dr. Marcus Conant began treating AIDS patients in 1981 and went on to become one of the dominant medical clinics in the response to AIDS in San Francisco (Bazar).

On the contrary, the American political establishment was far more reactionary in its response to the AIDS crisis. Reagan and his administration presided over the first eight years of the AIDS’ spread in the United States, and his response (or lack thereof) to the epidemic is nearly as infamous as the disease itself. When Reagan Administration Press Secretary Larry Speakes was asked about the disease in a series of press conferences spanning from 1982 to 1984, he responded with “a mix of laughter, homophobic jokes and general indifference” (Gibson). Reagan stayed silent on the epidemic for a majority of his presidency; his first earnest address regarding AIDS was in 1987, after almost 23,000 Americans had died of the disease (Gibson). In this address, Reagan rhetorically asked “don’t medicine and morality teach the same lessons?” furthering the notion that AIDS was a disease that punished “unsavory” individuals and contributing to the stigma which dramatically worsened the disease’s impact.

The passionate and impactful work of numerous activists combated the ignorance and bigotry that defined the government’s response to AIDS. In 1981, Larry Kramer, playwright and prominent gay activist, hosted a meeting in his apartment to discuss “the ‘gay cancer’ that was affecting their friends and lovers;” this meeting evolved into the formation of the group “Gay Men’s Health Crisis,” which raised money, established hotlines, and even performed medical research. Teenage AIDS victim Ryan White, who was initially banned from attending school after contracting AIDS from an infected blood transfusion in 1985, became a vocal advocate for AIDS awareness and destigmatization (UW Health, “Ryan White Overview”). Following his death, Ryan’s name was given to the largest federally funded program for those living with AIDS in America today, called the “Ryan White Care Act” (UW Health, “Ryan White Funding”).

Despite the massive number of Americans living with HIV today and the thousands of individuals who continue to be infected with the disease each year, the AIDS Crisis is largely seen to be over in the United States. This is partially the result of the development and widespread use of antiretroviral drugs, which control the viral load of HIV positive patients and have drastically reduced the lethality of the virus, and PReP, a pill which high-risk HIV negative individuals can take to reduce the likelihood of contracting the disease. In spite of scientific advancements, the United States Government’s problematic and slow response to AIDS has been ongoing since the height of the AIDS crisis; it was not until 2010 that the United States lifted the ban on HIV-positive non-citizens from entering the country, and Donald Trump recently praised scientists for a non-existent AIDS vaccine while cutting funding to many HIV programs in the administration’s 2018 budget (Lovelace).