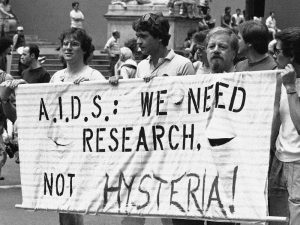

The other salient political legacy of AIDS is AIDS as a catalyst for gay politics on a national level. The omnipresent, inescapable impact of AIDS on the gay community in the United States coupled with the Reagan administration’s silence on the disease and the bias within the medical community forced gay men to mobilize politically; for the first time in American politics, the “gay vote” was a substantial and impactful political base, with election day estimates in 1992 expecting the gay vote “to exceed the Jewish turnout of four million voters, with some estimates gauging their number as high as nine million” (Schmalz).

Utilizing the organizing and fundraising strategies developed to battle AIDS throughout the decade prior, Gay groups had finally coalesced into a political mass large and wealthy enough to make an impact on politics on the national level. However, they needed a supportive administration in Washington; the political norm for years had been that “politicians of all stripes hid or returned financial contributions from homosexuals for fear of being tainted” (Schmalz). Gays found this support in the Clinton campaign in the leadup to the 1992 election. Clinton’s close friend David Mixner, a gay political organizer and AIDS Activist, called Clinton in the leadup to the election and insisted that, before he could get behind Clinton’s campaign, he needed to know “where you stand on AIDS and our struggle for our freedom” (Schmalz). This call, coupled with Clinton’s attendance of a meeting of “wealthy homosexual activists” in Los Angeles, “led to his pledge to fight discrimination against gay men and lesbians and to support a larger Federal commitment to combat AIDS” (Schmalz).

Clinton soon came under attack by Republicans for his “strong support of gay rights,” but remained unwavering in his stance, repeatedly stating that he believed the country “agrees with his opposition to discrimination” (Schmalz). A 1992 New York Times article declared Clinton’s stance “untested ground in a Presidential race,” and asked Clinton if “his pro-gay positions might be political suicide,” to which Clinton initially shook his head no, paused, burst out laughing and said, “maybe” (Schmalz). But the lid had been opened, and issues which had never been discussed on the political stage were now dominant issues in the race to the presidency.

The specific issues the gay community mobilized behind, “like whether homosexuals have a right to equal job opportunities or to serve in the military,” served as backdrops to the larger issue, poised in the same 1992 New York Times article: “whether America can accept homosexuality.” On top of this, it was a test to see if the gay community was still strong enough to make a political impact on the national level; at the time of the election, more gay men had died of AIDS than “the total number of Americans killed in the Vietnam and Korean Wars combined” (Schmalz).

(Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/was-first-major-news-article-hivaids-180963913/)

Despite the political agency which the AIDS movement catalyzed and the support found in the Clinton administration, most of the policy stemming from and relating to AIDS was not framed by or attributed to gay men or gay groups. Instead, the policies’ narratives focused on the minority of AIDS victims who were straight and became infected “by accident;” the most glaring example of this is the Ryan White Care Act, the largest federally funded HIV prevention fund. This program, which provides “a comprehensive system of HIV primary medical care, essential support services, and medications for low-income people with HIV,” was named after Ryan White, a teen who contracted HIV in 1984 at age 13 through a botched blood transfusion and, after five years of advocating for government awareness and action, passed away (UW Health). White was a pivotal figure in AIDS activism, and his memorialization though this act is well deserved. However, it is telling that the policy directed disease which primarily brutalized queer communities is not attributed to queer activists; gayness was so scorned and political that such a label would have been detrimental to policy’s success.

The support the gay community was found in the Clinton campaign and the Democratic establishment was met with strong pushback from Republicans and conservative groups; this led to the cementing of gayness as a partisan issue in the United States. Many fundamentalist groups at the time of the 1992 election denounced “homosexuality in even stronger terms than they do abortion, insisting that it is against God’s law” (Schmalz). These views were implemented into conservative-backed policy; one glaring example was Oregon’s 1992 Ballot Measure 9, which, supported by a campaign of hateful, fear-mongering anti-gay videos broadcasted throughout the state, attempted to legally classify homosexuality as “‘abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse’” and allow discrimination against homosexuals in Oregon” (Egan). Such policies were supported by evangelists as well as some Catholics and Orthodox Jews, all of which are prominent voting bases for the Republican party. In some cases, however, “gay-bashing turned people off” and became “a minus for the Republicans, admitted conservative political analyst Kevin Phillips in the lead up to the Clinton election; Clinton’s victory in the election and the failing of Oregon’s Ballot Measure 9 do not dispute this claim (Schmalz).