Polio was a medical disaster that disrupted the lives of many throughout the United States and the world. Medical disasters play an important role in evoking major themes in the scope of disaster study. They are slower yet have years when numbers peak illustrating the dynamics between slow and spectacle disasters. They also originate from uncertain sources intertwining the role of nature and of humans. In the US, the impact of Polio was relatively small in terms of the numbers of those infected and who died, as compared to other medical conditions such as cancer, tuberculosis, or cholera. However, it affected people much more than the numbers showed. Those who experienced more serious Polio symptoms suffered a great degree to the point where patients could not breath or walk. This disease paralyzed young children. Images spread in newspapers of children attached to machines, children in wheelchairs and crutches, and parents dismayed as to what to do. Polio infected a significant public politician known as Franklin Delano Roosevelt at a later age, and it took its place amongst movements for those with disabilities, for science and medical research, and for mothers to take a part in society. Stuart Galishoff states, “because of the pathos aroused by steel braces, iron lungs, and misshapen limbs, poliomyelitis gripped the public imagination more firmly than perhaps any other disease thus far encountered in the twentieth century” (1976, 101). This is a bold statement to make, but one that highlights how Polio had a widespread impact and touched the hearts of many. That said, the numbers were still high enough to make a mark. This was a disaster that traveled around unseen unless looked at under a microscope. Furthermore, Polio added to the US disaster plate arising during the World Wars, the 1918 Pandemic, the Great Depression among many others, all of which made healthcare more difficult. During the first decades, the disease overall remained behind the federal agenda of these major events leaving much of the responsibility to the States, and it was not until about the mid-20th Century when the fight against Polio in the US would be nationally prioritized.

Galishoff’s article was about how Polio affected Newark, New Jersey. After health officials declared the disease a threat, William Disbrow, President of the Newark Board of Health failed to acknowledge its existence claiming that “there was no more reason to fear infantile paralysis than any other disease” (Galishoff 1976, 103). In short, Disbrow downplayed the virus not wanting to worry the public, and was angry about the fuss everyone else was making. His lack of initiative led to other health officials taking things into their own hands. They initiated quarantines, disinfections of housing and clothing, stationed guards at homes where residents avoided quarantine, press articles, and public pamphlets in various languages to inform people about the disease (Galishoff 1976, 103-104). One-half to two-thirds of those infected were treated in city and county hospitals (Galishoff 1976, 104). What took place Newark was one example how Polio was responded to at the local level.

Here, this section will discuss a timeline and overview to how Polio played out in the US to give viewers an idea on the scale of the disease and what it looked like in society. Because this was a slower disaster in the US, and is one that continued globally, it is hard to pinpoint the pre and post disaster periods. Even though Polio did eventually die off in the US, people still experienced post trauma and permanent medical conditions. Polio was not something new in the US. People were already familiar with paralysis and what general illness looked like. Polio symptoms overlapped with those of many other types of viruses. The situation was also a learning experience, and aligned with and allowed for medical research that was coming to the forefront. Polio dates back to the ancient times (BBC 2015), but it became truly visible in the West, particularly in Europe, Canada, and the United States. The US first outbreak was in Vermont 1894 with 132 cases (Beaubien 2012). Then States in the Northeast and the Midwest grew in numbers. New York experienced 2,000 cases in 1907, Minnesota in 1910 had 1,000 cases, and Massachusetts had over 800 (Rogers 1989, 489). This took place while the US was starting to develop a better idea of and understand viruses, germs, bacteriology, and hygiene, and what these terms meant. 1916 was when the first major wave hit, especially in New York City. Polio conglomerated in Brooklyn and then made its way out (Oshinsky). Parents went to local doctors and priests asking why their children were going limp and even dying (Oshinsky 2005). This resulted in house-to-house inspections, people closing their doors to outsiders, and armed policemen guarding train stations and roads (Oshinsky). The 1916 outbreak lasted from June to October claiming about 6,000 lives and left 27,000 people paralyzed, the majority being in New York City (Oshinsky 2005).

Egyptian Stele dated 1403-1365 BCE of a Priest with a Walking Stick and Deformities Resembling Polio, BBC

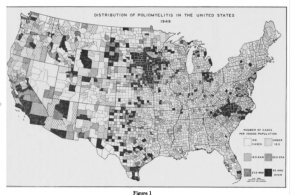

Titled: Distribution of Poliomyelitis in the United States 1948, Cases Per 100,000 (White: Zero – Black: 50+)

From Dauer, C. C. “Prevalence of Poliomyelitis in 1948.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 64, no. 23 (1949): 733-40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4586983.

In 1921, Polio paralyzed 39-year-old Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Oshinsky 2005). During his presidency in 1938, he founded the National Foundation of Infantile Paralysis also known as the March of Dimes movement (Oshinsky 2005). This organization was able to gather millions of dollars for research, education, and better medical facilities (Oshinsky 2005). It seemed all well and good, but the only way to stop Polio was with a vaccine. During the 1940s and 1950s, Polio approached its worst, infecting more adults. The numbers jumped from 8 per 100,000 in the early 1940s to 37 per 100,000 in 1952 (Oshinsky 2005). 1952 alone experienced 60,000 children infected, thousands left paralyzed, and 3,000 deaths (Oshinsky 2005). In 1946, President Truman declared Polio to be a threat to the US and finally framed it as a nationwide war (Oshinsky 2005). By the 1950s and 1960s, vaccines were developed and issued out, and in 1979, the virus was completely eliminated in the US. After the West conquered Polio, the developing world continued to struggle against it. The diseased prolonged in Africa and Asia. Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan are the only nations today that still contain Polio cases (Beaubien 2012). Polio provides a narrative to what a medical disaster entails, and how long it can take to eradicate a contagious disease of this vast scale. The current global fight is still not over.

Polio Globally, NPR