As the United States begins to research for and issue out a Covid-19 vaccine, this section will remind readers that the United States has experienced the vaccine process before with Polio. Yes, Polio was a very different disease than Covid-19 as it was an epidemic, not a pandemic, and not as contagious, but there are lessons that can be learned from this process. A question to ask when studying disasters is why do some events receive more attention than others? One answer could be that historical disasters arise again when they are needed for example the 1918 Pandemic and Covid-19. Covid-19 can be another reason to analyze Polio.

Poliomyelitis Overview

Before delving into Polio vaccines, this section will discuss what the Polio disease is which will help readers understand the historical background. Polio, short for Poliomyelitis, is a disease that infects the throat and the digestive track (CDC). It is often described as one that is difficult to understand because of the wide range of symptoms that are not always consistent among whom contracts Polio. Cases exemplifies how Polio mainly infects young children because it is caused in large part due to lack of hygiene, but it can infect adults as well (CDC). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most people will not show any visible symptoms and for those who do, the symptoms are very similar to the flu. These symptoms include sore throat, fever, nausea, headache, and stomach pain, typically lasting two to five days (CDC). If one contracts a more serious case, there are three categories (CDC):

- Paresthesia (described as a pins and needles feeling in the legs)

- Meningitis (Infection of the spinal cord and/or brain)

- Paralysis (Cannot move parts of the body, particularly weakness in limbs – arms and legs)

Polio can be a life-threatening illness (CDC). 2-10% of paralysis patients die because it affects their ability to breath (CDC). It is spread through person to person contact, most likely after contact of the feces waste of an infected person (CDC). Patients can also catch it from droplets of a sneeze or cough which is less common (CDC). There is no cure and must be treated with a vaccine prior to contracting the disease (CDC). Patients can also suffer from what is known as Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS) with symptoms including fatigue, muscle weakness, and joint pain (CDC), in addition to the Post Traumatic Stress.

CDC

Iron Lung Machines, The Early Ventilators, NPR

NPR

Ultraviolet Light, NPR

The Vaccines

Amesh A. Adalja highlights how the Polio vaccine narrative has really been a “Tale of Two Vaccines,” and this has been the story that dominates how people remember this journey. These two vaccines are used today in the few nations that still have Polio. In the early 1900s, Polio was treated with regular medical practices of the time, iron lung machines, ultraviolet light, crutches, braces, and wheelchairs.

After years of scientific research, the first vaccine to be developed was the IPV or the Inactivated Polio Vaccine (Adalja 2011, 87). It was developed by Dr. Jonas Salk in 1955 at the University of Pittsburgh (Adalja 2011, 87). Salk was able to develop the vaccine from “3 inactivated (“or killed”) Polio virus strains… and it is “administered in a series of 4 injections” (Adalja 2011, 87). The IPV has been determined to be “one of the safest vaccines in humans, whether used alone or in combination vaccines” (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2015). The trick was to develop a vaccine that would work against the three determined main types of Polio, and a “Wild” type detected in India later on (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2015). Salk incorporated the techniques of Scientist John Enders who was first to grow the virus in a lab earning him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1954 and Time Magazine’s Man of the Year in 1961 (Beaubien 2012).

The second vaccine was developed by Dr. Albert Sabin, known as the OPV or Oral Polio Vaccine during the same period as the Salk vaccine (Adalja 2011, 87), but was finally released in the 1960s (Oshinsky 2005). It was “made from 3 attenuated (“weakened”) live virus strains, and the determined advantage to the oral vaccine over the injected vaccine was that the live virus in the oral vaccine can combat Poliovirus producing “better immunity” (Adalja 2011, 87). The IPV was and is more commonly used in the developed world, while the OPV was primarily used in the developing world due to its “low cost, ease of oral administration, and ability to engender immunity in individuals who have not been vaccinated” (Adalja 2011, 88). Similar to any vaccine, the OPV and the IPV have not been perfect and there are many factors that have already and can still lead to failure, environmental, malnutrition, other health conditions, human tolerance etc. (Bandyopadhyay 2015).

Dr. Jonas Salk, IPV, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dr. Albert Sabin, OPV, University of Cincinnati

OPV, Global Polio Eradication Initiative

1955 Congressional Hearing

Administering vaccines not only requires scientific approval, but governmental approval as well. The responsibility of these government officials is to make sure that the vaccine is safe to give to humans. Part I of the 1955 House of Representatives Hearing titled “Poliomyelitis Vaccine” opened with this statement: “H. R. 6286, the administration’s $28 million poliomyelitis immunization assistance bill, and H. R. 6207, a bill designed to give authority to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, through an amendment of the biologics control law, to supervise and control, in the interest of protecting and preserving the health of the American people.” During a virus spread, scientists work hard to create a vaccine as fast as possible, and to make sure that little mistakes are made and if they are made, that they are caught. Scientists must also make sure that the vaccine works well enough and is safe to issue out to patients. It is important for vaccines to go through this long process as there are various factors to take into consideration – is the vaccine safe, what are the side effects, does it work, what will be the cost, who should get it first, how will it be distributed nationally and internationally etc. Again, the opening of the hearing states “protecting and preserving the health of the American people.” The hearing went on to listen to multiple experts and politicians in order to come to plausible solutions. The principles of the hearing were as follows:

- “Safety of the vaccine must be the paramount consideration, and the questions relating to safety in quantity production must be deter- mined by the best scientific advice, uninfluenced by any other factors.”

- “The vaccine must be distributed on an equitable basis among the States and among individuals within the States.”

- “Children should be able to receive the vaccine regardless of the ability of their parents to pay.”

- “Any distribution system adopted must be as practical, fast, and effective as is possible while still meeting the foregoing principles.” (House of Representatives 1955)

Dorothea Horstmann

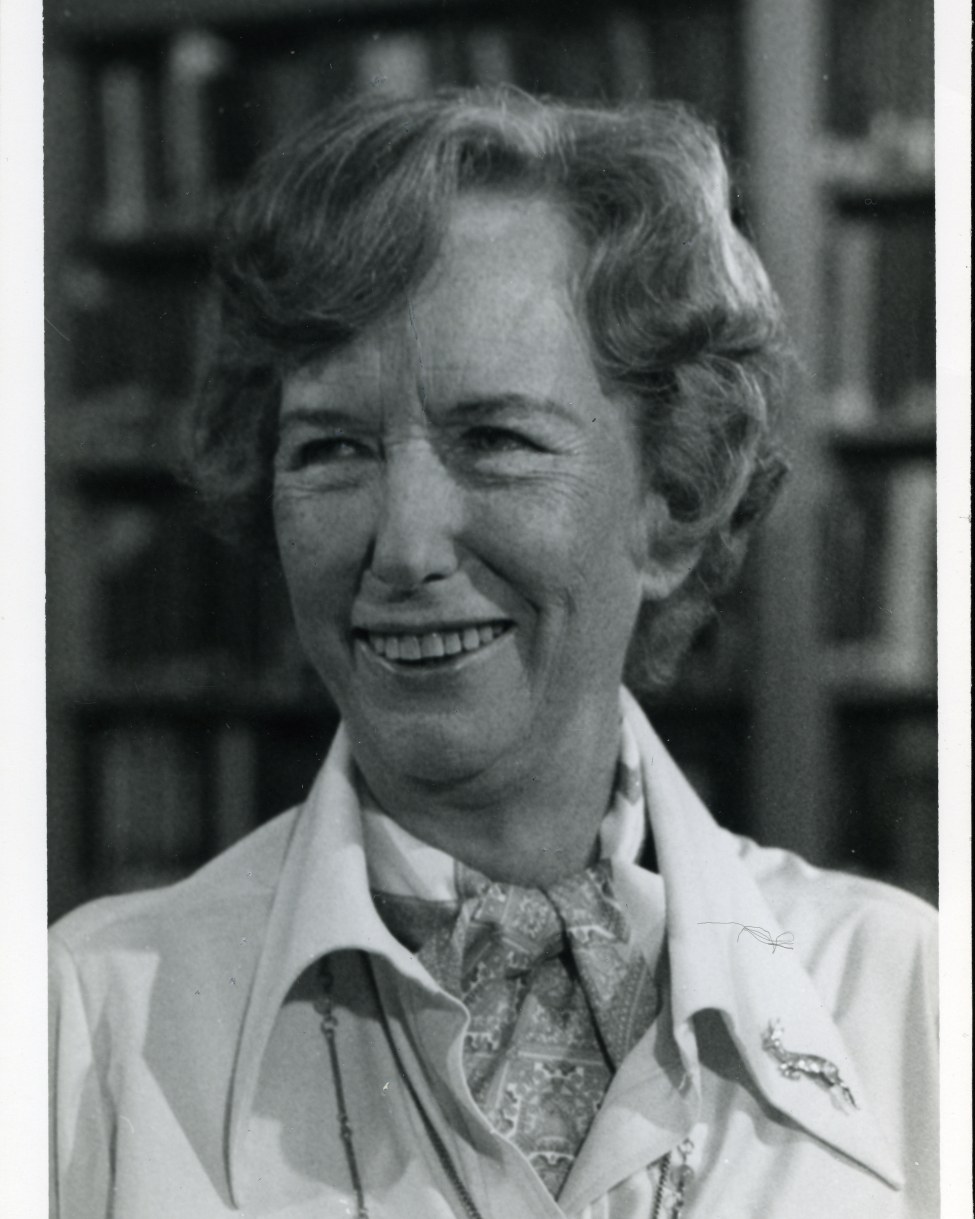

David Oshinsky wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book and an article for the Yale School of Medicine, and within his article, he emphasizes how there were hundreds of men and women behind the scenes that contributed to the final vaccine product yet since they were behind the scenes and were numerous, they were outshined by Salk and Sabin (2005). One of these workers was Dorothea Horstmann and she played a pivotal role in Polio research for the vaccine. After graduating from medical school, she had difficulty finding a job in higher levels of the medical field as she was a woman (Oshinsky 2005). She eventually was hired at Yale due to a mix up; her employers realized she was a woman after accepting her application (Oshinsky 2005). During her Polio research, Horstmann made an interesting discovery. She figured out that Polio enter in the blood stream for a brief period of time before symptoms arise where it becomes vulnerable, a detail easily missed by other doctors (Oshinsky 2005). Her research paved the way for the vaccine. Horstmann’s work was recognized and other doctors were able to validate her research, but she was hidden behind the shadow of the men who received credit for the vaccine. Oshinsky dedicates a large portion of his research to her work. She became the first female professor of medicine at Yale and came to be highly praised for her achievements (Oshinsky 2005). Horstmann was representative of the many men and women who worked tirelessly for the vaccine behind the scenes and who go unrecognized. Her story is essential in this narrative because it acknowledges how there is much more information and people of a disaster situation that have yet to be uncovered, and that have been lost, buried in the load of information, or intentionally hidden. Voices like hers alter the narrative – women did take action and had a much more crucial role than taking care of their sick children, being bedside nurses, and fundraising. Julie Des Jardins in her book The Madame Curie Complex covers the “hidden history of women in science.” She writes, “this book is not overly laudatory of female accomplishment in science, but it isn’t a victimology either” (Jardins 2010, 2) … but rather “truism to assert that the personal and professional, private and scientific, are intertwined in these pages” of women in science (Jardins 2010, 3).

Dr. Dorothea Horstmann, Yale School of Medicine

We can learn lessons from this vaccine process. Some big take aways are the history of hiding diverse voices, and the necessity to balance speed and safety of a vaccine. So, as we wait and see about the Covid-19 vaccine, we will have to hope for the best and continue to send gratitude to our frontline workers.