Polio’s Differential Effects

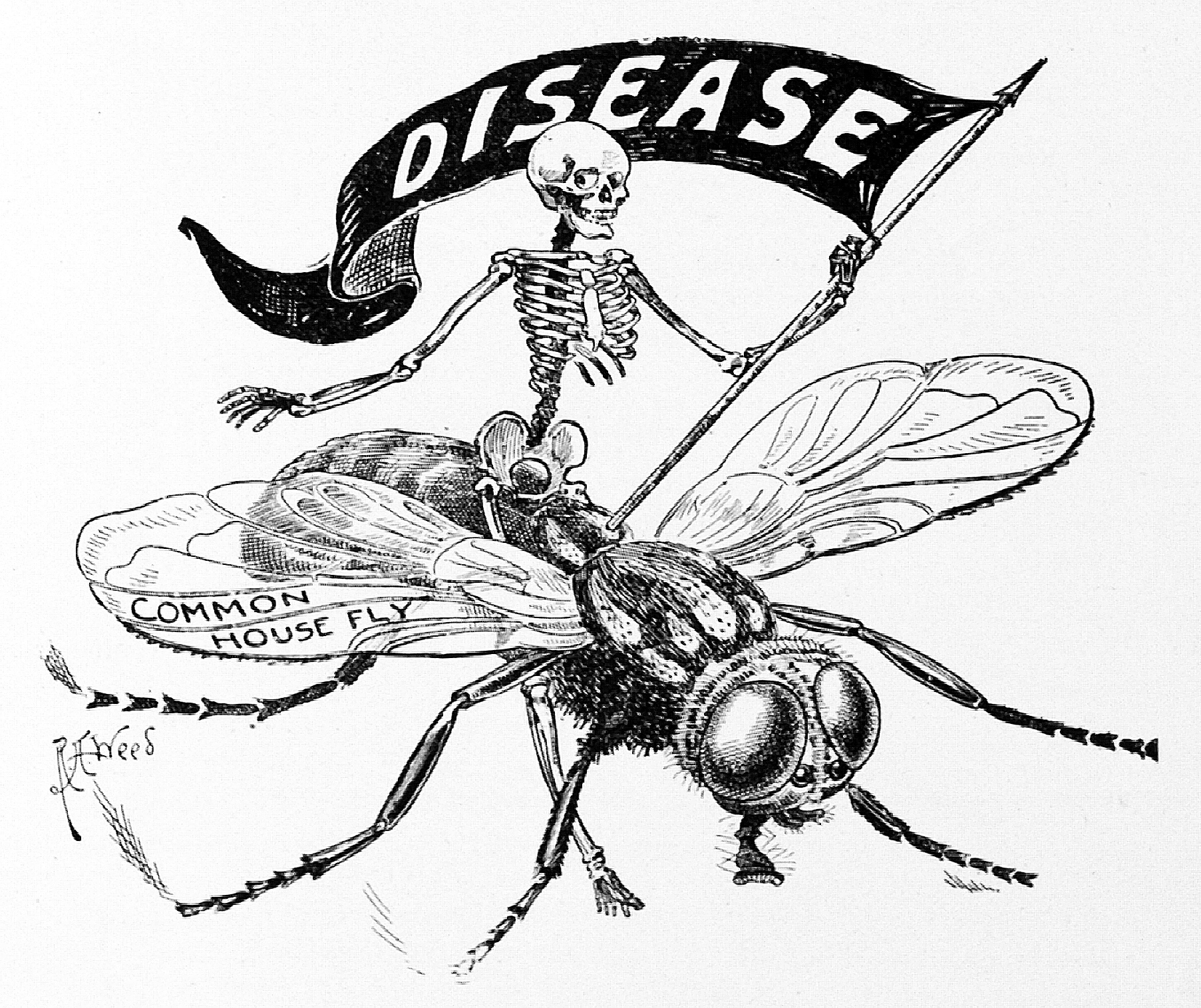

Differential effects are important to the study of disaster because it helps us glimpse into who was infected, and uncover groups of people that may have been ignored, forgotten, or overlooked in the narrative. These effects delve into the specifics of the “lived experience” of the people who were impacted. Disasters themselves do not discriminate, but various groups are affected differently based on location and geography, race and ethnicity, socio-economic status, gender, and types of government and relief organizations. Polio was visible for about a century in the United States and was able to span across the country. Therefore, the disease affected many different groups of people distinguished by age, race, gender, socio-economic status, physical ability etc. It would be expected for those who were marginalized, lower impoverished classes and communities of color, to not have access or the funds to afford the best healthcare or to best prepare themselves to battle Polio. We also saw the disease infecting young children, most likely since Polio was spread through fecal waste, yet it is important to note that adults did get Polio as well. However, this was not the entire story in regard to differential effects. Polio essentially came out of nowhere and during the 20th Century, and even today, people did not fully understand the science behind the disease. This knowledge gap left room for speculation and arbitrary reasons on what caused the disease and who to blame. Polio did not discriminate among its victims as the both the poor and the more affluent were affected (Rogers 1989, 490). That said, in the early years of epidemiology, scientists targeted poor families with congested and rundown homes filled with animals because these factors were associated with filth and germs even though Polio also hit new homes and single-family households considered hygienic (Rogers 1989, 493-494). In addition, there was a tendency to scapegoat immigrants who were blamed for bringing Polio from the outside world (Rogers 1989, 494). Nature was also a proposed source of the disease to take attention away from the upper-class families of whom Polio impacted. Within the nature explanation, seasonal insects were determined to be potential causes to take fault away from middle to upper class nonimmigrant hygienic families who contracted the disease, turning attention back to the poor (Rogers 1989, 498).

https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/1805

Specific Case Studies

Due to the Polio epidemic having such a slow and vast scope, individual case studies give us a better idea on its differential effects. Linda Mason Dunn provided a first-hand account of her mother contracting Polio in 1946, and how Polio being “an epidemic of unknown origin” opened the door to many possible ideas given by her family members on where her mother was first infected (67). Her grandmother believed that it came from a chill during roller skating (Dunn 1997, 67). Her mother thought it came from eating contaminated peaches touched by flies (Dunn 1997, 67). Her grandfather suggested that her Polio came from “exploring a hermit’s cabin” that was “filthy with green flies and garbage” (Dunn 1997, 67). Lastly, her family also turned to “general filth” but that was ruled out because the grandmother was a “good housekeeper” (Dunn 1997, 67-68).

Another case study is looking at Vermont. Vermont was the first major State outbreak recorded in 1894 with 132 cases. Since this was a relatively small number, Vermont does not always receive attention for its role in the narrative. Elisha Renne’s article from the Vermont History Journal focuses on Montpelier in 1917. Renne argues that even though Vermont was not even close to the scale of New York in 1916, this case study demonstrates how medical and cultural beliefs shaped the Polio narrative (2011, 162,164). In Montpelier, contrasting theories and methods persisted. Dr. Charles Caverly believed in quarantining and limiting the size of gatherings (Renne 2011, 164). The Diary of Dorman Kent emphasized the need to alter “personal habits” to control filth and pollution (Renne 2011, 164-165). Kent’s theory was replaced by the “germ theory” supported by Robert Koch who explained how Polio came from “specific entities, germs, which… could be contained without regard to environmental, social, cultural, or political concerns” (Renne 2011, 165). There were various reactions to these theories. Some stayed and quarantined, while others left the city or sent their children away for a while (Renne 2011, 171). Others opposed the quarantine, especially those who were not infected and who believed the science was unclear (Renne 2011, 174-175), also including people who had to work.

Prominent Movements

There were two marginalized groups in American history who come to forefront of the Polio epidemic, women and people with disabilities. Women took a more active role in raising awareness and funds for the cause due to Polio infecting their children, displayed by the photo below, and in becoming nurses. This was an example of women being liberated in disaster situations yet constrained as they are staying within the reigns of the domestic sphere.

Grace Kelly and the Mother’s March, Yale School of Medicine

The second group, those with disabilities, were also an important part of the narrative. Polio aligned with the rising disabilities movement in the mid to late 20th Century. Amy Fairchild writes, “in the early years, polio was a hidden, shameful disease associated with filth, poverty, and outsiders” (2001, 497). People with Polio were not as accepted in society. Those with wheelchairs and who were attached to iron lung machines were looked upon shamefully and called names such as “The Boiler Kid” (Fairchild 2001, 499). This story was shifted by powerful people and disability activism towards a narrative of which technology was a “vibrant part” of those paralyzed by the disease (Fairchild 2001, 498), an image which Fairchild deems an “aura of uniqueness” (2001, 490). Frederick Snite, a wealthy 25-year-old from Chicago influenced the media to portray the wheelchair as a way to give Polio victims a sense of freedom (Fairchild 2001, 499). President Franklin Delano Roosevelt also changed the narrative as he could camouflage his Polio paralysis to give not the appearance of sadness but of “charisma, vigor, and… recovery” (Fairchild 2001, 500).

Disabilities Movement, Georgetown Law

Marilyn Saviola was Paralyzed by Polio and Joined the Disabilities Movement in the 1960s, New York Times

How did President Roosevelt’s Warm Springs Provide Insight on Differential Effects?

When President Roosevelt transformed the Warm Springs Resort in Georgia to a rehabilitative center for Polio patients in response to previous Polio segregation policies, many examples of differential effects were uncovered when his facility was established. Warm Springs began as a symbol of wealth as President Roosevelt poured money into renovations and the best doctors attracting wealthy patients “seeking…another possibility for healing” (Rogers 2009, 149). The center was kept from being viewed as a hospital hiring “bathing beauties,” female physical therapy graduates, and “good-looking young men” to portray the facility as a spa (Rogers 2009, 150). In addition, being in Georgia, Warm Springs started as a “whites only refuge… careful not to challenge what [Roosevelt] termed ‘local customs’” (Rogers 2009, 151). Naomi Rogers further notes, “African Americans were employed as maids, waiters, body servants, gardeners and janitors” (2009, 151). Finally, Warm Springs also became the location for disability activists who spoke up for paralyzed patients “neglected and poorly treated,” who trained “employers to see the physically disabled as worthy employees,” who brought awareness to Polio which was deemed second to other diseases, and who “presented handicap as a psychological rather than a physical barrier” (Rogers 2009, 151-152,154). These activists formed the National Patients Committee with its slogan being “Every Patient, A Polio Crusader” (Rogers 2009, 152).

Little White House Historic Site of Warm Springs, National Park Service

Little White House Pool, National Park Service

Little White House Pool, whitehousehistory.org