Science fiction means many things to many people. Asimov defined it as “that branch of literature which deals with the reaction of human beings to changes in science and technology.” Pohl defined it as something that should “predict not the automobile but the traffic jam”. I would argue that good science fiction is a synthesis of these two definitions, a distinct way for us to speculate not only to glean predicaments of the future, but unfurl how the present propagates them. Through science fiction we have an avenue to explore how our bodies are attempted to be appropriated, physically or metaphorically. In tales of the robotic, especially in tales of piloted robots, we can begin to drill down the ways that this appropriation takes place in the military-industrial complex. In examining the real robot genre, often dominated by Japanese tales evoking experiences under an imperial military, we can better understand what that militarization has the potential to do under neo-imperial American policy.

Robotics, as a general topic, occupies a special place in the sci-fi pantheon, particularly in the ways it allows us to explore human form. Bodies are spaces that each individual is entitled to, the space in many ways integral to their experience of the world. Stories like Simak’s “Desertion”, Merril’s “That Only a Mother”, or even Le Guinn’s “Nine Lives”, exhibit some of the ways that science fiction probes at the idea of how integral our bodies are to our experience of the world. When folded into robotic tales, stories like Hoshi’s “Bokko-Chan” bring about the ways that idealization of form and body have interplay with the rest of science fiction’s imaginations of the body. More often than not, robots represent independent beings, worthy of an exploration of their own psychologies (such as in Aasimov’s “Reason”, Aldiss’s “Supertoys Last All Summer Long”, or even the thought readers in “Thought Control”). But as creations of order and control, robots will often cross into themes of authority and power. Once one crosses over into observing the use of robots as avatars, things start to get interesting. In particular, it gives us an opportunity to explore the ways that that authority can be used against us.

In Tynan Brook’s excellent essay, “The First Idol Anime Was Actually About State Power”, they bring up an incredible point about the Macross franchise: the giant humanoid robots represent some possession of the body as apparatus of the state. I would extend the argument a little further in saying the majority of major real robot anime, if not anime representing mechanization of otherwise analogue functions, will often bring in some aspect of possession, whether by the state or larger forces. Giant robots, especially as extension of robots, while often presented as power fantasy, are still descendants of the word robot: slave.

Within the reality of Macross, the main giant robots, Variable Fighters, present this possessive relationship with the state as something that demands any given pilot bonds themselves as humanoid bodies with the weaponry they operate. This is made more poignant by the fact that VFs transform between plane, humanoid robot, and literally something in between. As a pilot, your humanity is something at whim of the state, and the ideal soldier is able to mould it perfectly into whatever weapon is required of the moment. In OVA(Original Video Animation) Macross Plus, this relationship is extended by the experimental VF-21. Unlike previous units, the pilot has to mentally link with the unit, operating the mecha in all forms as if it were an extension of the pilot’s limbs, breaking down the metaphorical barrier entirely. As perfect soldier of the state, Guld has to graft his own perceptions of his body onto that of the VF-21, no matter what shape it currently assumes. Instead of simply needing the skill to operate both humanoid and vehicle, Guld has to become a vehicle of the state.

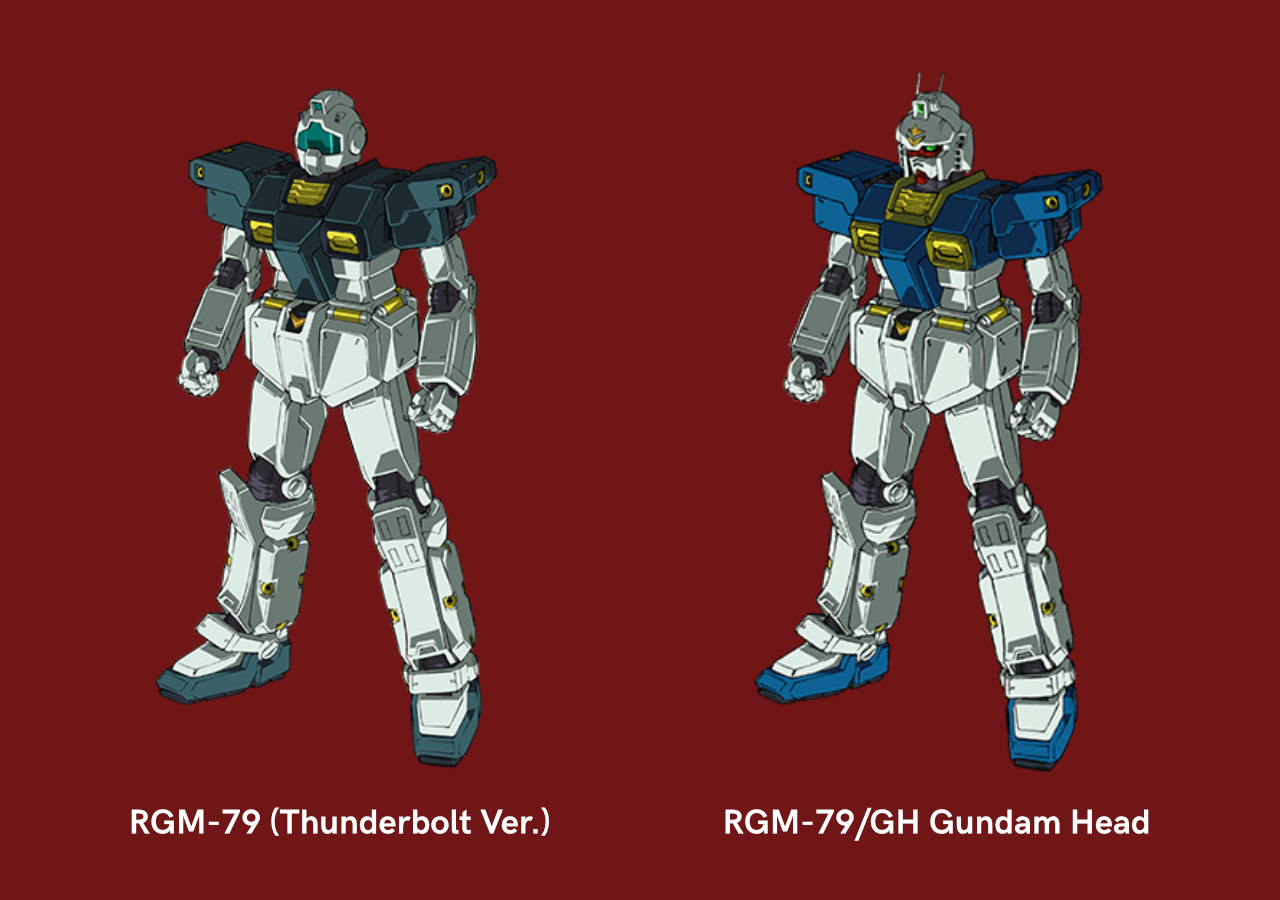

Gundam, especially in its Universal Century iterations, absolutely conforms to these standards. Mobile suits across the franchise represent an extension of each of their pilots, a simultaneous personalization of vehicular combat that strips away the personality of individuality by way of mass produced body, perfectly tuned for the state’s needs. Individual expression, whether in the form of custom colors or specialized mobile suits, are only granted to the pilots who best serve the state. Gundams, each often unique prototypes, represent the ultimate expression of individual unit, but also the ultimate divorce from individual pilot, as one no longer represents themselves: they represent the pinnacle of the EFSF state’s might. In Mobile Suit Gundam, Amuro Ray may be the White Devil to Zeon’s forces, but any Gundam following him represents the shadow of the Federation’s imperial might. In Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt: December Sky, ace pilot Io Flemming, no matter how uniquely insidious a fighter he may be, was exclusively known as “the Gundam pilot” by the Zeon remnants he fought against. Your operation of a Gundam may distinguish you from the average grunt, but that just means you’re under further scrutiny, and policing, by the state, as you not only pilot a body belonging to them, you operate a body representing them.

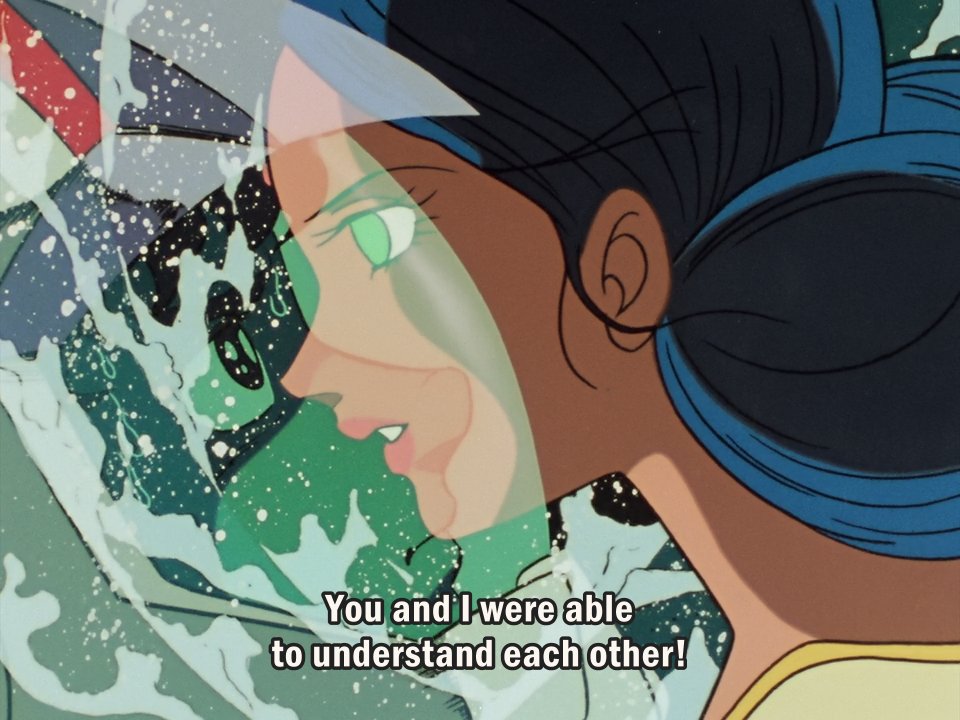

This body problem is exacerbated by the unique mutations of Gundam, specifically newtypes, and their combat uses. As essentially psychic empaths, technology developed to the point of allowing them to operate their suits as their bodies. Their personalization within state body is exacerbated by the fact that they can psychically link, and empathize with, other humans. Original Gundam pilot Amuro experiences this in flashes across the series, and at one point vividly witnesses the death of an ally through her own eyes, while he’s unable to save her. While attempting to defend a ship carrying his friends, he psychically experiences the rage and sorrow of an enemy commander, avenging her deceased husband. For a newtype, they aren’t a humanoid vehicle fighting alien humanoid vehicle. They are person fighting person, and no amount of steel can stop them from experiencing that.

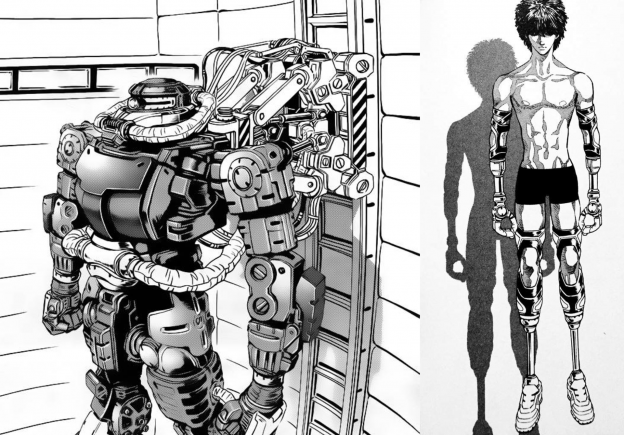

Some have it even worse. Gundam Thunderbolt’s Daryl Lorenz operates as part of Zeon’s Living Dead Corps, a mobile suit sniper unit comprised mostly of injured, amputee pilots who otherwise struggle to use operate the complex controls with their low quality prosthetics. After a particularly disastrous mission, and with the looming threat of Io Fleming and his Gundam, his commander has his remaining uninjured limb amputated by his unit’s medical department in order to allow him to interface with the Psycho Zaku II, a unit that directly connects its systems to his nervous system. In a heartbreaking scene, while testing the unit, one realizes that piloting the Psycho Zaku is the closest to human that Daryl has felt in a very long time, given his clumsier prosthetics have otherwise hindered him to the point that operating a standard suit is far more difficult to operate. Like many of his peers, outside of the horrific carriage made to represent his leaders, Daryl’s meat and blood body has been claimed, directly and indirectly, by the state.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0ReyyMEreg

Other properties have pushed this to its absolute limit. In Hideaki Anno’s seminal work Neon Genesis Evangelion, the namesake Evangelions are early on revealed to be less metallic vehicle, as opposed to massive, unstable organic creature used as a vehicle of the main organization NERV. They’re piloted by a small group of troubled, essentially orphaned teenagers who synchronize their nervous systems with the mecha in order to operate them. This is done by entering the units through a cockpit called and entry plug, which inserts itself into the spine of the Eva. These units are then used to combat similarly large alien creatures called Angels, that have been invading Earth. Late into the series, the horrifying truth is revealed: the Evas are mutated human-Angel hybrids who’ve been constructed with the soul/essence of each pilot’s deceased mother, restrained by a combination of their binding armor and the fact that without an entry plug, their nervous systems are non-functional. In this framework, Eva displays the wider familial effects of a complete consumption of body by state, and an exploitation of shared trauma somewhat inherent to the current military structure. Through its use of the relationship between mech and pilot, and the ways that both are exploited by the authorities above them, the show is not only a rumination on personal trauma, but also an exploration of the ways that this trauma can be abused by state bodies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A89blUjT7z8

Across the real robot genre, mecha’s relationships with their pilots as state avatars provides us an credible lens into the ways that states enforce power now, and the ways that it can extend into the future. In the context of the USA, a government often rearing to flex its imperial might, it is essential that its citizens understand just what kind of part its state is expecting it to play, and how far down that mode of control can dig with little vigilance. Science fiction is an essential companion to any vigilant citizen, for a deep understanding of speculation often relays a deeper understanding into the present being speculated upon.

Kidô Senshi Gundam. Animation, Action, Drama, Sci-Fi. Sotsu Agency, Sunrise, 1979.

Macross Plus. Animation, Sci-Fi. Bandai Visual Company, Big West, Mainichi Broadcasting System (MBS), 1994.

Matsuo, Kou. Kidô Senshi Gandamu Sandaboruto Dissenba Sukai. Animation, Sci-Fi, War, 2016.

Shin Seiki Evangelion. Animation, Action, Drama, Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Thriller. Gainax, Nihon Ad Systems (NAS), TV Tokyo, 1995.

Zeria. “The First Idol Anime Was Actually About State Power.” Floating into Bliss (blog), May 6, 2019. https://floatingintobliss.wordpress.com/2019/05/06/the-first-idol-anime-was-actually-about-state-power/.