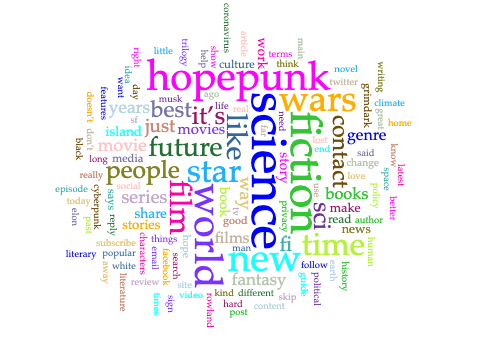

After scouring the webs for science fiction related articles that piqued my interest, these are the words that appeared most often. I chose not to actively remove words from the word cloud—there didn’t seem to be that many causing mayhem, so I left them there. Thus, these are all 125 of the most common words that I encountered on my searches.

It is no surprise that “science” and “fiction” appeared as much as they did—I was actively seeking out websites and articles related to science fiction.

I have to admit, I was somewhat surprised to that hopepunk was the fourth most common word I encountered. I certainly did do a fair amount of reading about hopepunk, especially more recently, but I didn’t expect it to feature quite this prominently. Nevertheless, I have become quite intrigued by hopepunk, or at least hope in science fiction. This is what I wrote my manifesto on, of course.

Grimdark made its small appearance too, as did fantasy. I did find it interesting how my inspiration for my manifesto initially came from fantasy. After watching the tv show The Magicians devolve into hopelessness, I grew quite frustrated at this phenomena. I certainly devoured A Song of Ice and Fire by George R. R. Martin, and enjoyed his masterful worldbuilding, plot, and characters, but at the end of the day, I’m not a fan of the nihilism and hopelessness omnipresent in the series and in the genre.

As I began to turn towards science fiction with an eye on hope, I began to really appreciate hope in science fiction all the more. And I was fascinated how easily I found a bridge between science fiction and fantasy—it didn’t feel forced. This is the path I took to my manifesto, and it shows in this word cloud.

Coronavirus made a small appearance here, which is not all that surprising. So did climate—I am involved in climate action, and was interested to find where science fiction and climate intersected. Twitter also made an appearance, as did Elon Musk (both his first and last names—my, my). I’ve been quite interested in Elon Musk for a few years now. Though I’m not a fan of his, I’m interested in why his messages and work speaks to so many people. And those messages and works certain overlap with and draw from science fiction. His child’s name is just the latest example.

There are plenty of other words on there too, including many of the usual suspects in science fiction. World was the third most common word, which is not surprising. Star Wars was there—I certainly sought out a few articles about the films, but I was surprised to see both words highlighted so prominently (no doubt aided by other non-Star Wars related stars and wars). In fact, film was also highlighted quite prominently—a reminder that science fiction is still known to most through film. Combined, films, film, movies, and movie, would form the largest word together. New and time both featured prominently—two words that are quite present in science fiction and in writing in general.

Many more words formed the word cloud, but these were some that stuck out to me, and felt particularly significant.