Science fiction is for nerds: nerds, twerps, geeks, dweebs, Trekkies. People make fun of people who read sci-fi, people who go to comic cons, and read comics. This is such a tried and true trope, perhaps second only to playing D&D, that it’s written into nearly all coming of age movies. Thus, bullies being who they are, science fiction gets made fun of…a lot. Why? Because its really funny, that’s why. Because a shark with frickin laser beams isn’t out of the question in science fiction, that’s why it gets made fun of. So, when science fiction is made fun of, when a genre that is constantly ‘demanding to be taken seriously’ is the subject of the comedy, what can we make of it? Is there that we can really take from away from Spaceballs? Yes. An emphatic yes. Perhaps of all the forms of science fiction, comedic science fiction strips away the frills and dressing of science fiction, it presents us with an unencumbered view of the genre for what it is, what it is trying to say, and most importantly, why you should be reading it (specifically Kurt Vonnegut).

Ok, so I’m telling you to read, write, watch, listen to, look at, or consume in any form science fiction. This raises an important question, what is science fiction? It’s a tough question to answer, critics Mark Bould and Sherryl Vint say “There is no such thing as science fiction.” American science fiction writer Norman Spinrad says “Science fiction is anything published as science fiction.” Who is right, Bould and Vint or Spinrad? I would say both, in fact, I think they agree more than they disagree. To Bould & Vint’s point, there really is no such thing as science fiction, there is no one marker or trope or method or dead giveaway that tells us “this is science fiction” or “this is not science fiction”. In science fiction comedy, this blurred line gains a useful utility. The lack of gatekeeping or boundaries let us, as consumers or critics, take a wide view of what falls into the science fiction pile. This lets us consider Mel Brooks and Isaac Asimov in one breath or the Lonely Island and PK Dick in another. The science fiction community is far reaching and open, there is no barrier. When we consider Bould and Vint’s idea in that light, they agree with Spinrad. As Spinrad rightfully claims, the only real labels we can put on Science Fiction are those that some stuffy editors put on the inside jacket of a book. The worlds of possibility in Science Fiction are truly endless so there is limited use in trying to box it in. With this literary sandbox as the canvas, comedy writers and artists have embraced science fiction as a fantastic medium for social commentary and satire.

Let’s start in film, among the genres of Science Fiction comedy, film is perhaps the most accessible. Comedy film, more so than comedy writing, is a common and accepted part of the average consumers cultural consumption diet. In this field, geniuses like Mel Brooks and Mike Myers have carved out niches for themselves, poking fun at the establishment and creating art that is equally low bro and provocative. At face value, Spaceballs is a cheap shot at Star Wars and a low shelf VHS that panders to an immature audience. While this might be true, the film also folds in commentary about the sameness of science fiction culture and the overuse of common tropes. Han Solo becomes Lone Starr, a bumbling mercenary in a Winnebago spaceship with a half-man, half-dog (mawg) sidekick named Barf. Yoda turns into Yogurt, Darth Vader into Dark Helmet, and Jabba the Hutt into Pizza the Hutt. When Lone Starr jams Dark Helmet’s radars, the Winnebago sends a massive jar of jelly at the radar’s and the radar screens start oozing raspberry preserves. The Austin Powers trilogy, Myers’s spoof of James Bond has similar elements—time travel, common plot lines, rocket ships, and moon bases make up the crux of each movies plot. Although the moon base isn’t quite “The Sentinal”, there is something to be said for Austin Powers fighting Mini-Me in zero gravity. In other Black Adder, Space Quest, and Futurama all create brilliant pieces of comedy that satisfy one’s science fiction craving and are good for a good laugh.

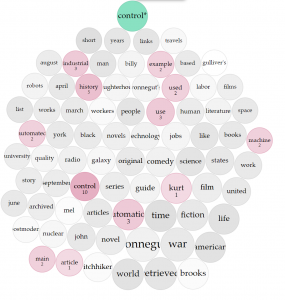

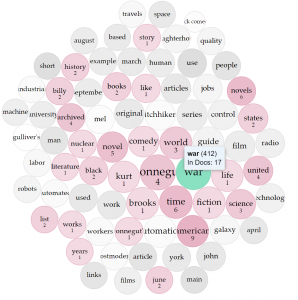

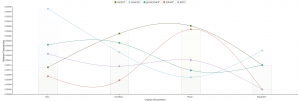

In the written word, I could go on and on about various authors, stories, and collections of pointed science fiction humor (“Repent Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman”, “How Erg the Self-Inducting Slew a Paleface”, etc.) but no science fiction writer has summited the comedy mountain quite like the god himself, Kurt Vonnegut. In a quartet of science fiction books, Vonnegut does more for science fiction comedy and makes most astute critiques of the world as it is then nearly any other writer. Player Piano, Cat’s Cradle, God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, and Slaughterhouse-Five set the bar for science fiction comedy, and it’s a high one.

In Player Piano, Vonnegut takes the reader into the world of automation, industrial society and late capitalism to explore the damage wrought on a man’s soul from losing his purpose in life to a machine. The social critique is cheeky and astute. One of the two protagonists, the fiction Shah of Bratpuhr, a distant far away land, calls all the American citizens Takaru. In Bratpuhr this means slave, but the closest American definition is citizen. The unknowing Americans take the name with pride, pride Takarus in a mechanized society. Written in the post-war boom, the novel is a tactful critique of the effects of an organized and planned society where every man and woman has a role and place in the order of things.

In Cat’s Cradle, Vonnegut tackles religion, a challenging matter to say the least. The fictional religion, Bokonism, is a strange assembled culture littered with references and novums. In the religion there are karrasses: groups of cosmically linked people, duprasses: a karass of two people (like a loving couple), fomas: lies that hurt no one, and, the most poignant, granfaloons: a false karass or a group of people who thinked they are linked but cosmically, are not (college alumni, religions, fandoms, etc.). Cat’s Cradle for all its eccentricity, forces us to think about how we live our lives, who we associate with, and what to make of those relationships.

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (or Pearls Before Swine), takes another crack at the world as it is, this time it challenges the inequality and absurdity of capitalism and wealth. The main character, Eliot Rosewater, is a discontented heir. The name is a combination of man of the people FDR and free market champion Barry Goldwater. Eliot is just the same, a member of the elite who spends his days toiling in Rosewater County, Indiana as a Volunteer Fire Chief rather than taking up the reigns of a family empire from his US Senator father. Years before universal basic income was a buzzword in national election, Vonnegut introduces the idea convincingly.

Vonnegut’s classic, although they’ll all amazing, is Slaughterhouse-Five (or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death). In this selection, the author turns the lens of criticism on his own experience. The auto-biographical story follows a Vonnegut-like pacifist through the European theater of World War II, surviving the bombing of Dresden, back the United States for a healthy fight with PTSD, and onto the far away planet of Tralfamadore where time acts differently. “The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist” (Slautherhouse-Five). Writing for a generation who had seen the greatest destruction in mankind’s history, Vonnegut invites the reader to stop and consider what really matters (if anything).

So, I’ve just thrown a bunch of stories at you, but why does science fiction comedy matter still? Eliot Goldwater says it best:

“Eliot admitted later on that science-fiction writers couldn’t write for sour apples, but he declared that it didn’t matter. He said they were poets just the same, since they were more sensitive to important changes than anybody who was writing well. “The hell with the talented sparrowfarts who write delicately of one small piece of one mere lifetime, when the issues are galaxies, eons, and trillions of souls yet to be born. (God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater).

Science fiction writers write about what matters and science fiction takes that difficult message and washes it down with some sugar. Life, death, war, inequality, society, culture, any of this has been written about again and again. If we’re going to listen to the same takes again and again, we might as well have some fun with it, and if you don’t think sharks with freakin laser beams are fun, I’m just not sure we’ll ever see eye to eye.

Works Cited

Vonnegut, Kurt. Cat’s Cradle. Penguin Books, 2008.

Vonnegut, Kurt. God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater ; or, Pearls before Swine. Dial Press, 2006.

Vonnegut, Kurt. Player Piano. Dial Press, 2006.

Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children’s Crusade: a Duty-Dance with Death: a Novel. Modern Library, an Imprint of Random House, 2019.