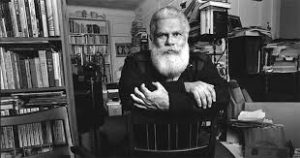

In “Racism in Science Fiction,” Delany speaks to his experience being considered as the “first” African-American science fiction writer, an “originary label [worn] as uneasily as any writer has worn the label of science fiction itself.” He reflects on his experience at a particularly charged Nebula Awards, in which a speaker publicly denounced Delany’s work and, to defuse the tension, our beloved Asimov joked that “You know, Chip, we only voted you these awards because you’re Negro…!”

While his untimely comment may seem both crude and uncalled for, Delany explains that Asimov’s quip held a much weightier significance, as it suggested that “the concept of race informed everything about [him].” Delany goes on to cite other names that have frequented our class discussions, Judith Merril and James Blish, whom referred to Delany, in print, as a “handsome Negro” and a “merry Negro,” respectively.

While Delany’s experience with racism in the science fiction community may feel foreign to us now, over 20 years later, it is essential that we (as science fiction consumers, and some of us, writers) recognize the importance of supporting a diverse group of voices that, for better or worse, are imagining and extrapolating our collective futures.

While Delany’s experience with racism in the science fiction community may feel foreign to us now, over 20 years later, it is essential that we (as science fiction consumers, and some of us, writers) recognize the importance of supporting a diverse group of voices that, for better or worse, are imagining and extrapolating our collective futures.

Full essay: https://www.nyrsf.com/racism-and-science-fiction-.html