Julian Kawalec’s “I Kill Myself” can be read as a compelling account exploring the dangers of absolute power’s capacity to seduce and corrupt. While this is certainly one aspect of the story, I believe that the story itself delves deeper into voicing many other concerns present in 1962 Poland, which found itself in a world of tense nuclear escalation in which it watched from the sidelines as two world superpowers continued to build to an uncertain potential world ending clash.

Kawalec’s “I Kill Myself” follows the unfolding events surrounding one unnamed senior lab assistant’s interactions with the fictional Zeta bomb, a weapon powerful enough to destroy everything on Earth. Generally, these fears persisted through the Cold War, especially as the nuclear arms race escalated. What I think makes this story so interesting is its close proximity to an event that happened only a year prior. In 1961 the USSR tested the newest addition to its nuclear arsenal, the Tsar Bomba. The Tsar Bombais still the single most powerful weapon ever detonated in human history. What’s more is that this title persists despite the fact that it was tested at only half its full strength due to fears that a full-strength detonation would shroud the USSR in radioactive nuclear fallout. Another popular, yet ultimately unfounded, concern was that a nuclear explosion of that sheer magnitude would cause the Earth’s atmosphere to ignite, killing life on this planet. International scrutiny followed the Tsar Bomba’stesting and, the next year, Kawalec published his story on the fictional bomb that could single-handedly end life on this planet. “I Kill Myself” reflects many of the concerns that existed in Poland at this point in the Cold War.

One Cold War concern appears even through the mere existence of a weapon like the Zeta bomb. A persistent source of anxiety through the Cold War was that there existed weapons with the capacity to cause an unparalleled level of global destruction with incredible ease. The Zeta bomb is so powerful that even our current conception of death is not sufficient in understanding the destruction that would ensue. Kawalec writes that “if it were to explode, the result would not be death, for death is an equal partner with life… In comparison with the consequences of an explosion of Zeta, death is something anodyne. The term ‘death’ doesn’t apply to the effects of that” (Kawalec, 261). While reading the story, I felt a persistent tension in understanding that a distance between the Zeta bomb contact pin and critical point, a mere three millimeters, is all that separates life as we know it and instantaneous global annihilation(Kawalec, 260). Each time that the narrator handled, moved, or caressed the Zeta bomb I felt a twinge of tension purely due to the knowledge of the world ending destructive potential that sat just beneath the trigger pin. The experience as a reader looking in mirrors the knowledge that persisted in the Cold War that people outside your control hold in their hands the capacity to end global life as we know it at any time with the flip of a switch. This concept leads into another concern of who exactly has the right to access such a weapon and for what purpose do they hold that power?

During the Cold War, Poland found itself in a position near the geographic center of the divide between East and West. Its status of being at the mercy of the relations between two foreign powers was clear. The concern was not just that there existed weapons that could effortlessly bring about global destruction but was also that these weapons were in the hands of people set opposed to one another. In “I Kill Myself,” I found myself questioning who has the right to have access to the Zeta bomb? Despite all the described security checkpoints, how is it that an unnamed, incredibly average lab assistant could readily access and abscond with a weapon that could destroy the planet? From the point of view of nations like Poland, this could conceivably have been a very real question. To the rest of the world, nuclear weapons were handled and under the authority of nameless, random personnel. And how could anyone, no matter how distinguished, be sufficiently qualified to wield world ending power? They might as well have been nameless lab assistants.

Certainly these operators, being human, are not infallible, raising the concern of the corrosive and seductive nature of power. This is perhaps the most clearly shown concern in “I Kill Myself” as the once noble narrator overtly became fixated on and seduced by the bomb’s power. The reader views first-hand the transformation very clearly through the account of the narrator. For the first half of the story, he is described as “quiet… and docile” and as someone who is willing to shoulder the pain of loneliness and loss in order to make the ultimate sacrifice in protecting all of creation, not just humans but also the birds, the worms, and the trees(Kawalec, 262). Yet, we witness the progression of his mission being one of sacrifice to using Zeta for good to using it to destroy the wicked, to forcing beneficial reforms, to arbitrarily bending individuals to his will, to achieving riches, to satiating his own personal lust, to degrading and humiliating others, to achieving fame and power, and even to becoming God (Kawalec, 266-267). Ultimately, he continues to assert that he is acting in the interests of the greater good yet, to the reader, the actions he describes are clearly self-interested to a perverse extent. And yet, in the context of the Cold War, both the US and the USSR undoubtedly believed themselves to be acting for the greater good. What does this reveal about the reality of the real world that Kawalec found himself in?

Finally, there also existed a concerning sense of futility and even inevitability. Even if the narrator did not deviate from his original noble plan, I wonder if his actions would have made any kind of difference. He seems convinced that throwing the Zeta bomb into the mud of a marsh and throwing its contact pin into a river would definitively eliminate the Zeta’s dangerous potential because “who will ever find a pin only a little thicker than a needle” (Kawalec, 263). In a society that places so much importance on the Zeta bomb and has the technological means to create such an advanced machine, would they truly not have the ability to either comb the area to find the bomb itself and replace the missing contact pin or simply recreate the Zeta bomb even if the narrator had succeeded in also destroying the physical notes on the process available to him? Even before the narrator’s fall I had the persistent feeling of futility and doubted that his actions in disposing of the bomb would have any true lasting effect in eliminating the risk. I predict that Kawalec and much of the world that just had to watch the Cold War unfold shared these sentiments of futility and possibly inevitability.

Works Cited

Kawalec, Julian. “I Kill Myself” (1962). Ed. Maria Kuncewicz. The Modern Polish Mind. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1962. 260-267.

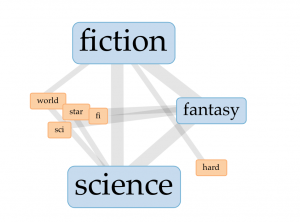

references to other SF titles, like the laser trails from Tron’s iconic laser bikes. The cosmetics for wheels, paints, and car toppers also often feature sleek glowing designs and reference SF titles like Rick and Morty, Beat Saber, Portal 1 & 2, Mad Max, Fallout, Dying Light, Oddworld, Warframe, Blacklight: Retribution, Back to the Future, etc. Even the cosmetics that aren’t references to specific SF titles still convey a strong SF vibe. For example, a wheel selection titled “Mothership” features rubber lined by a grid of glowing green streaks. Antenna toppers take forms like classic UFOs or the iconic green alien heads.

references to other SF titles, like the laser trails from Tron’s iconic laser bikes. The cosmetics for wheels, paints, and car toppers also often feature sleek glowing designs and reference SF titles like Rick and Morty, Beat Saber, Portal 1 & 2, Mad Max, Fallout, Dying Light, Oddworld, Warframe, Blacklight: Retribution, Back to the Future, etc. Even the cosmetics that aren’t references to specific SF titles still convey a strong SF vibe. For example, a wheel selection titled “Mothership” features rubber lined by a grid of glowing green streaks. Antenna toppers take forms like classic UFOs or the iconic green alien heads.

experience, I barely made it off my starting planet, which just happened to have an incredibly acidic atmosphere that would literally eat through the lining and life support of my space suit if exposed for too long. I discovered new animal species, plant types, and I explored some abandoned settlements that were nestled deep in underground tunnels (away from all the acid in the air at the surface). Once I got off planet, I aimed my ship at the next nearest planet and

experience, I barely made it off my starting planet, which just happened to have an incredibly acidic atmosphere that would literally eat through the lining and life support of my space suit if exposed for too long. I discovered new animal species, plant types, and I explored some abandoned settlements that were nestled deep in underground tunnels (away from all the acid in the air at the surface). Once I got off planet, I aimed my ship at the next nearest planet and